Harry Potter: How the boy wizard enchanted the world

- Published

What JK Rowling said about first Harry Potter book in 1997

Can you believe it's 20 years since the publication of Harry Potter and the Philosopher's Stone?

Joanne Rowling, as she was known then, dreamed up the story of the bespectacled boy wizard on a train trip between London and Manchester.

She finished the manuscript in 1995, writing much of it in cafes in Edinburgh while her baby from her first marriage slept in a pram.

After many rejections, the manuscript was eventually picked up by Bloomsbury. The first hardback print run, which came out on 26 June 1997, was just 500 copies.

Then something magic happened. That first book - and the six that followed - went on to sell more than 450 million copies around the world.

Here's a look at the many ways the Harry Potter phenomenon has cast a spell on the cultural landscape over two decades.

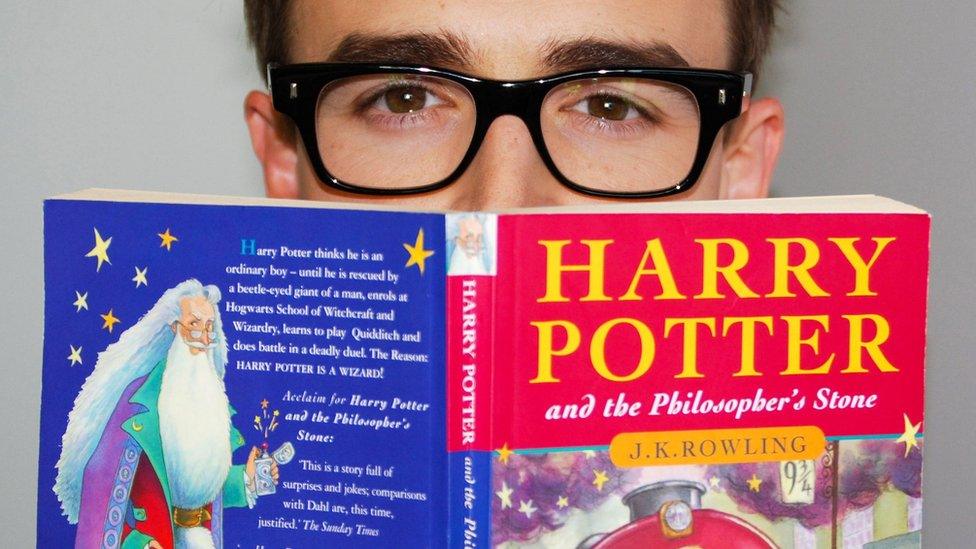

It got kids (and adults) reading

The Potter books have sold more than 450 million copies

Okay, so books were around for a long time before Harry Potter. But JK Rowling turned book consumption, especially for children, into something close to addiction.

You want proof? The UK release of Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban in 1999 was timed at 3.45pm to prevent children in England and Wales from skipping school to get their copy.

The later books got HUGE but it didn't stop kids devouring them.

Grown-ups got hooked too, with the books being released in adult-friendly covers.

The book releases themselves became headline news: when the fourth book Goblet of Fire came out in 2000, booksellers around the world got together to coordinate the first ever global midnight launch.

When Rowling received an honorary degree at St Andrews University that same year, the Scottish institution said she had proved that children's books "are still capable of capturing and enchanting an immense audience, irrespective of the competing attractions of television, Nintendo, Gameboy and Pokemon".

It also got people writing

Harry Potter fans at the premiere of the final film, the Deathly Hallows Part 2

The Harry Potter books are credited with opening the way to a whole swathe load of young adult fantasy fiction.

Lots of books were released in the hope they would be "the next Harry Potter", such as Artemis Fowl, The Spiderwick Chronicles and A Series of Unfortunate Events.

Would we have had blockbuster series like Twilight and The Hunger Games novels had not Potter paved the way?

And let's not forget fan fiction.

The internet is thrumming with tens of thousands of unofficial spin-off stories about life at Hogwarts, The Dursleys and what the Weasley twins get up to at parties.

A warning to the curious: some are NSFW.

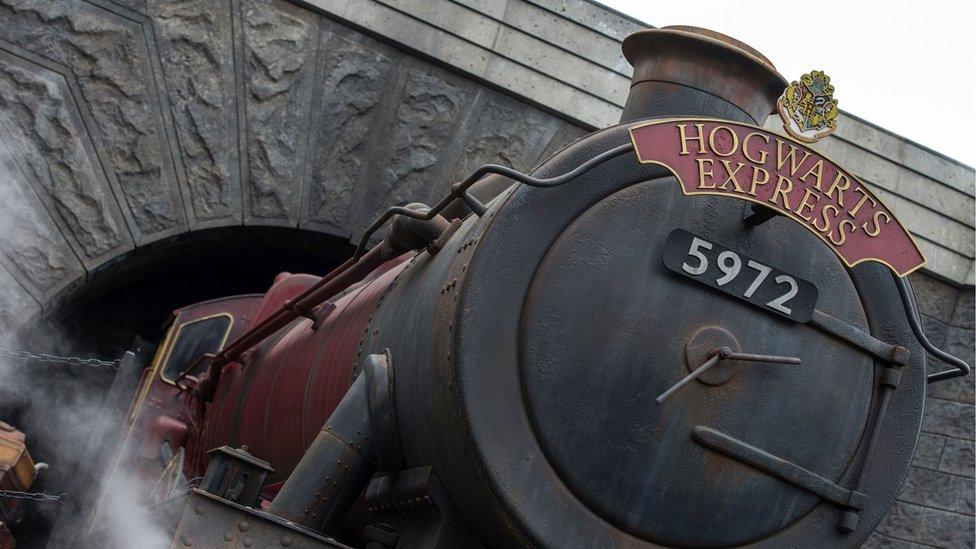

It got us all steamed up about trains

For a generation of kids brought up on Thomas the Tank Engine and The Polar Express, there was suddenly a shiny new steam train in the engine shed.

Yes, the Hogwarts Express.

No trip to King's Cross Station in London is complete without a selfie on Platform Nine and Three-Quarters, external.

It introduced new words to the dictionary

The Royal Mail produced special stamps based on the book covers

Most words have to be around for 10 years before they will be considered for the Oxford English Dictionary, but JK Rowling's word "muggle" - which made its debut in Philosopher's Stone - was an exception.

It was added to the OED in less than half the usual time, appearing in 2002 as "a person who lacks a particular skill or skills, or who is regarded as inferior in some way".

In the world of Harry Potter, a muggle is a person without magical powers.

We suspect that Crumple-Horned Snorkack - an elusive magical creature in Sweden - may take longer to make it into the muggle lexicon.

It invented a new sport

Watch Quidditch being played at the world cup

In the books, Quidditch is a magical sport played on flying broomsticks, and involves bludgers, quaffles and a golden snitch - a small ball with wings.

In the real world, Quidditch is a non-magical sport played on broomsticks, and involves bludgers, quaffles and a golden snitch - a person in a yellow t-shirt with a Velcro tail attached to their shorts.

It started in the US around 2005 and has become a global sport with its own governing body. The Quidditch World Cup takes place annually and was won last year by Australia.

It spawned one of the world's biggest film franchises

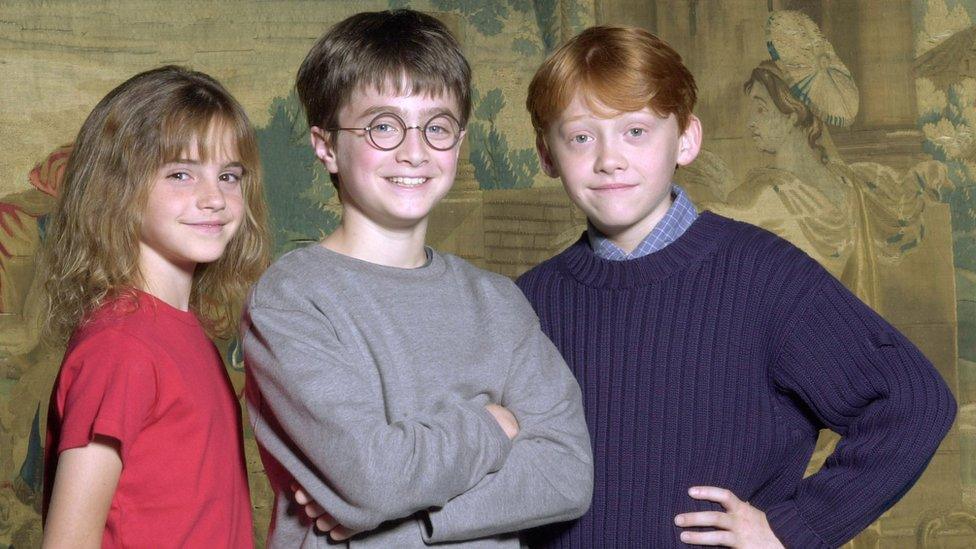

Young stars: Emma Watson, Daniel Radcliffe and Rupert Grint

Until recently, the eight Harry Potter films were the largest-grossing film franchise in history, having brought in a whopping $7.7bn (£6.1bn) worldwide.

The first Harry Potter film - Harry Potter and the Philosopher's Stone (it was known as the Sorcerer's Stone in North America) - was released in November 2001.

As well as breaking box office records faster than a trip on the Knight Bus, it also introduced the young Daniel Radcliffe, Emma Watson and Rupert Grint to the world.

The final film, Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows Part 2 (2011) is the highest grossing of all the Potter films at $1.34bn. It's the eighth-highest grossing film of all time, external.

The franchise - now known as JK Rowling's Wizarding World - has continued with the spin-off Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them (2016).

And there's plenty more to come. Rowling has said she has planned scripts for a total of five Fantastic Beasts films.

It cast its spell on the theatre too

Noma Dumezweni (Hermione Granger), Jamie Parker (Harry) and Paul Thornley (Ron Weasley) in Harry Potter and the Cursed Child

Harry Potter and the Cursed Child opened in London in 2016 to the same kind of Pottermania that surrounded the release of the books and films.

Some 1,500 fans at the very first performance, many dressed as witches and wizards, gasped at the various plot revelations and stage illusions.

The two-part play begins with Harry, Ron and Hermione in their mid-30s as their own children head off to Hogwarts school.

It even had critics reaching for superlatives. One wrote: "British theatre hasn't known anything like it for decades and I haven't seen anything directly comparable in all my reviewing days."

The play won a record-breaking nine prizes at this year's Olivier Awards.

Cursed Child will be opening on Broadway in New York in 2018 and JK Rowling has said she would like it to be seen widely around the world.

It's helped shape the millennial generation

Is anyone worse than Voldemort?

Millions of people reaching young adulthood have never known a world without Harry Potter.

Many who've grown up with the books can now get regular doses of JK Rowling via social media - she's got an army of almost 11m followers.

When Donald Trump was compared with Lord Voldemort last year, Rowling tweeted, external: "How horrible. Voldemort was nowhere near as bad."

She later mocked Twitter users who threatened to burn her books.

One response read: "Guess it's true what they say: you can lead a girl to books about the rise and fall of an autocrat, but you still can't make her think."

Twenty years on from that first book, it looks like no-one's going to be saying "Avada Kedavra" to Harry Potter anytime soon.

Follow us on Facebook, external, on Twitter @BBCNewsEnts, external, or on Instagram at bbcnewsents, external. If you have a story suggestion email entertainment.news@bbc.co.uk, external.

- Published26 June 2017

- Published2 May 2017

- Published13 April 2017

- Published9 April 2017

- Published2 February 2017