Facebook Watch and the reinvention of TV

- Published

Founder and CEO of Facebook Mark Zuckerberg: transferring more power to users

Ok, perhaps today is the day that Mark Zuckerberg finally abandons the pretence that Facebook isn't a media company.

It was a year ago that, on a visit to Rome to see the Pope, he said "We are a tech company, not a media company". , external

Then, in December, he appeared to soften his language, external, saying "It's not a traditional media company. You know, we build technology and we feel responsible for how it's used."

In a blog post in December I argued that Zuckerberg's firm was indeed a media company, because it is funded by advertising, creates vast amounts of stories (or content), and is the main source of news for millions - if not billions - around the world.

Today, with the launch of Facebook Watch, a video service that will incentivise the creation of a new industry in original programming, the tech giant is moving into broadcasting in a big way.

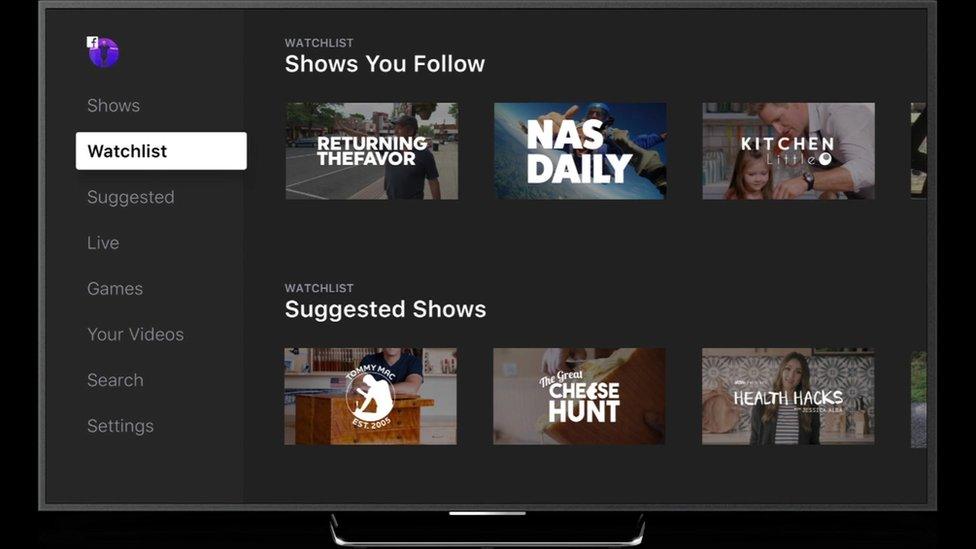

Facebook: Users will soon see a new Watch tab that will offer a range of shows

It is becoming a destination for viewers of programmes.

That, of course, makes it a media company; but qualifying for that label isn't a matter for pedants alone. This is about more than semantics: it's about Facebook's ambition, social obligations, and the future of media itself.

Vast ambition

It is actually quite hard to fathom the financial power of Facebook today.

Despite warnings last year about a limit to how many ads users will tolerate on their news feed, the company is able to charge brands ever more for the privilege of appearing there.

Its market capitalisation now nudges $500bn; advertising revenues are up 47%; and earnings by GAAP (Generally Accepted Accounting Principles) have hit $4bn - growing by a scarcely comprehensible 70% in a year, from a very strong base.

Mix that kind of growth and wealth with the Silicon Valley mindset - "move fast and break things" - and you get a sense of why Facebook has decided to move into original programming, giving the makers of videos that appear on its platform a juicy 55% of ad revenues - for now at least.

This is all about making the Facebook experience ever more sticky: making users want to spend more and more, and more and more time within the walled garden - or echo chamber or filter bubble if you will - of the social network.

With more than two billion users now, Facebook wants to do ever more to retain the interest of those logged on. High quality videos will do that, as will the company's eventual move into live sports, which has long been rumoured, but is yet to materialise.

'Social' media

Power brings responsibility, and there have been times when Facebook has seemed uncomfortable with its social obligations.

For instance, on the issue of fake news, despite hiring thousands of new moderators, the company is determined not to be an arbiter of what is true or false, preferring its community of users to make such judgements - or outsourcing them to fact-checkers.

At base, firms such as Facebook and Google are just ad companies. New ones, of course; unusually technical, too; and astonishingly powerful - but ultimately, they are companies who sell a product to advertisers.

That product is our personal data.

Just as it is hard to fathom the financial firepower of some of these Silicon Valley firms, so it is hard to grasp the amount of personal data they now control.

This data is vulnerable, because lots of people (including foreign powers and cyber-criminals) may want it; valuable, as these companies' wealth proves; and often handed over by people who are not fully clear about what they are doing.

Two excellent recent articles show that the social obligations created by Facebook's possession of this personal data are now receiving the kind of scrutiny and debate they deserve.

The Financial Times' John Thornhill has argued that this data is akin to the oil in Alaska, which was used to fund a version of the universal basic income idea (UBI) that has gained traction in recent years, as a way of addressing the rapidly diminishing share of wealth making it to the labour force in advanced economies.

Thornhill suggests Facebook should use its wealth to fund a UBI experiment. , external

Meanwhile, in his latest brilliant piece for The London Review of Books, John Lanchester explains how Facebook has made products of us all., external

"Facebook is in essence an advertising company which is indifferent to the content on its site except insofar as it helps to target and sell advertisements", Lanchester argues - though Facebook would deny the charge of being indifferent.

He goes on: "For all the talk about connecting people, building community, and believing in people, Facebook is an advertising company."

Indeed it is. And now that it is selling adverts in programmes that will be broadcast through its platform, via Facebook Watch, an interesting question arises. Should such shows be regulated by Ofcom? If not, why not?

Yes, the likes of Facebook are a new kind of media company. But we must believe that broadcasters have a social responsibility, because we have a regulator for them; and perhaps, if the broadcasts are taking place in the UK, the platform on which they appear, and the provenance of that platform, is secondary to the content.

Democracy in action?

Across media, power is shifting to audiences. The idea of editors determining what you can read, or commissioners determining what you watch, is weakening. Schedules are becoming obsolete, albeit slowly.

Facebook Watch will accelerate this trend.

With a user base massively bigger than YouTube and Netflix combined, the social interactions you conduct when logged onto Facebook - meticulously recorded by the social network's algorithms, of course - will now help drive the promotion and distribution of content.

How this works for users is impossible to know just now, of course. It could mean that we lose the serendipity of switching on and seeing what's occurring. But the loss in serendipity is, for most users under 35 at least, easily outweighed by the gain in being able to see what you want, where you want, when you want.

Convenience is king, and Facebook is making it more convenient to enjoy viewing experiences without leaving its platform.

Zuckerberg would justifiably argue this is a way of transferring more power to his users.

Lanchester is right: you are the product. With Facebook Watch, you are the programmers, too.