Weinstein: Is the media complicit?

- Published

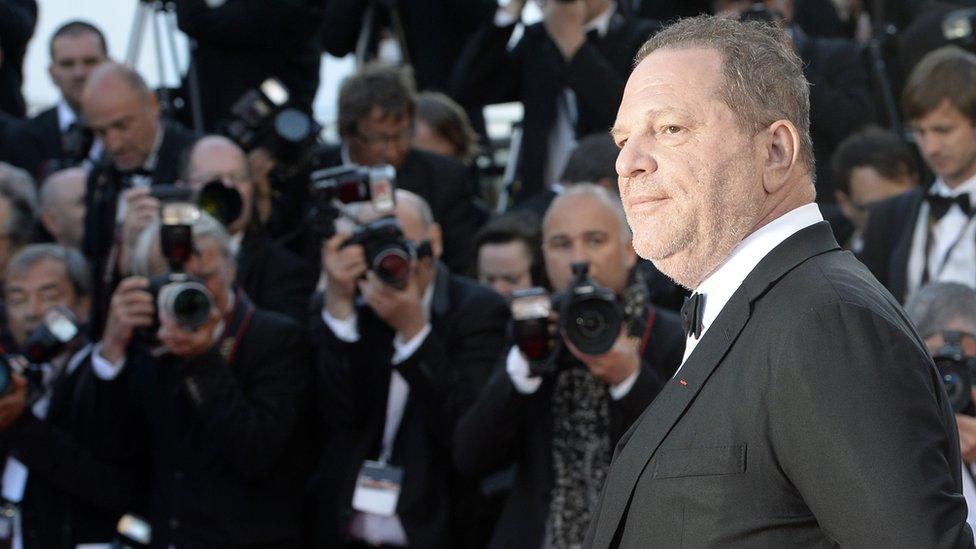

Harvey Weinstein: his relationship with the media has spanned four decades

Is the media complicit in the sordid scandal of Harvey Weinstein's alleged sexual bullying?

That is one of the explosive accusations swirling around the web this week, and deserves interrogation.

The answer to that question is textured and complex, rather than definitive and simple.

Complicity itself comes by degrees, and is not confined to the media of course.

There are those online, unsurprisingly vast in number, who say that the women Weinstein allegedly abused - he denies the bulk of the allegations against him - are themselves complicit. They should have spoken out years ago, apparently.

I must say I find this reasoning intellectually limited. It transfers the moral failure from Weinstein to his alleged victims, and penalises them for an absence of courage which few people could muster.

Then there is the question of whether people who knew Weinstein well - friends, actors, colleagues in the industry - should have spoken out earlier. I find this more plausible; but the evidence of other cases of sexual bullying, from the late Roger Ailes to Jimmy Savile, is that few people who know of their vile behaviour are willing to speak up.

Finally, there are the enablers of Weinstein's alleged casting couch sessions: the executive assistants who sorted logistics, the agents who sent actresses to his rooms; the finance chiefs who allegedly arranged settlement payments to those he'd intimidated. Of course, some of those around Weinstein may genuinely have not known what was going on.

This is a large group of people, and many of them will rightly both hate themselves, and fear exposure for their complicity.

But what of the media? Does the media also share blame for his alleged history of sexual harassment?

How close is Harvey Weinstein's relationship with the media?

Three kinds of complicity

The case against the media rests on three pillars.

First, the extent to which individuals in the media belong to my second category above, of those who knew Weinstein well and knew what was allegedly going on.

Second, specific instances of stories not being published, often for fear of legal action.

And third, the culture of reciprocity and mutual dependence which exists between journalists and all industries but is, in the case of showbiz, perhaps most prone to ethical failure.

Let's take these in turn.

I have been to parties in Manhattan hosted by Weinstein and some of the most famous journalists on the planet, attended by luminaries ranging from the world of politics to art.

Harvey Weinstein hosted many cocktail parties in New York with his estranged wife Georgina Chapman

Manhattan and Hollywood are rumour factories. Just as there are people at Fox News who suspected Ailes was a sexual predator years ago, so it would be astonishing if there weren't hundreds of journalists who heard rumours about Weinstein; and in some cases knew of specific allegations against him.

On the second, Ronan Farrow made an explosive allegation when speaking to Rachel Maddow this week. Farrow, who broke the story of rape accusations against Weinstein in the New Yorker, said that he had offered it, in publishable form, to NBC. It has been reported by HuffPost, external that NBC had concerns about the sourcing of Farrow's story.

As an Editor, you are often brought stories that need to be stood up, as the saying goes. In other words, you need to check the facts and sourcing, balance what is known against the values of your organ and the likely response to publication, and come to a decision as to whether or not you go for it.

Naturally I wasn't privy to the conversation between Farrow and his bosses at NBC, so don't know why they came to the decision that they did. But given the weight of evidence in his New Yorker story, and given the rigorous standards that organ applies to fact-checking, it does seem that they missed a phenomenal scoop.

NBC have now said that the story Farrow brought them lacked the strongest elements of that which The New Yorker published. This is in Brian Stelter's account of how the scoop slipped, external.

Ronan Farrow had been working on his story for ten months

Certainly if I were in charge of the editorial operation at NBC, I would think: damn, we've let a legendary scoop go to a rival. There is no evidence yet that cowardice or conspiracy stopped NBC publishing, but it was certainly a terrible miss, as this report in the New York Times explains, external.

Next we come to the allegation that the New York Times squashed the story when it was brought to them by the journalist Sharon Waxman in 2004. Though he wasn't at the New York Times then, its current Executive Editor, Dean Baquet, has provided a strong refutation, external of that claim.

Given that, to paraphrase Mark Twain, a lie can today travel around the world while the truth is putting on its shoes, there are huge numbers of people, some of them intelligent, who are circulating the claim online that the New York Times did indeed sit on this story for years. They would do well to read that statement from Baquet.

Culture of clientism

Finally we come to the most troubling possibility: that the media, because of its dependence on Weinstein for stories and access to stars, and because of the over-close and indeed fawning relationship between entertainment journalists and celebrities, allowed him to escape censure because they needed him.

In a series of tweets, external this week, Times writer Hugo Rifkind put this case eloquently.

"The constant fuss about closeness between politics and media? Showbiz and glossy media has left that for dust for a century," he wrote. "Showbiz media seems to have been a tool he used to intimidate - planting stories, raising careers etc. Complicit".

This is precisely the line of thought that Tina Brown, who worked closely with Weinstein for years, provided in an excellent interview, external with Newsnight on Wednesday evening.

By this account, Weinstein, like the most astute politicians, was a master at preventing the publication of negative stories about himself by handing out salacious gossip about other famous people, or granting access.

Tina Brown has worked with Harvey Weinstein for many years

It is worth saying that journalists covering every industry face these dilemmas. You might get a story which is bad for one of your best contacts. You put the story to them; they beg you not to run it, and say by the way if you hold off on that story, here's a fantastic scoop about someone else.

The temptation to keep your contact sweet, and to run with the alternative story, is immense - though it is a moral imperative for all journalists not to be bought off in this fashion.

I must say that on the basis of my time in journalism, Rifkind is right: in entertainment journalism, which is so utterly dependent on access to famous people - though, done bravely and well, it ought not to be - there is an insidious clientism which goes further than in most other sectors.

In the thousands of words and dozens of news reports and video clips that we have all read and seen about Weinstein over this past week, it has become abundantly clear to me that a culture of enablers around him did, sadly and unforgivably, extend to journalists who didn't pursue suspicions and rumours about him - not just because of a fear of legal repercussions, but because they felt they needed him.

Against all that, I should say that I believe The New York Times deserves credit for breaking the first of these recent accusations. When they exposed Roger Ailes of Fox News as a sex pest, they were accused of having political motivations. Now they have taken on a ghastly lion of liberal America, with strong connections to the Democrats.

A question of trust

Plenty of people say you can't trust the mainstream media.

And it has to be said that the parlous finances of many news organisations makes it much harder to take on powerful individuals and vested interests. Lawyers and editors and fact-checkers cost a lot of money - the sort of money that increasingly can only be afforded by the likes of The New York Times and New Yorker

Acknowledging that is not to forgive the media for failing to break this story earlier. Several journalists have come forward over the past week to say they had a sniff of this story but it got away; others were cowed by legal threats; and NBC should have turned Farrow's raw material into a legendary scoop for themselves.

Above all, journalists who heard whispers about Weinstein, over what appears to be decades of sexual bullying, but who relented for fear of jeopardising their own careers, made an unforgivable miscalculation.

So while we applaud those behind the latest revelations, at a time when the mainstream media is under assault, we are forced to conclude that - together with the assistants, agents and other industry enablers - yes, journalists were complicit in the alleged sexual career of Harvey Weinstein.