Lost 'Nazi art' shows aim to reunite masterpieces with true owners

- Published

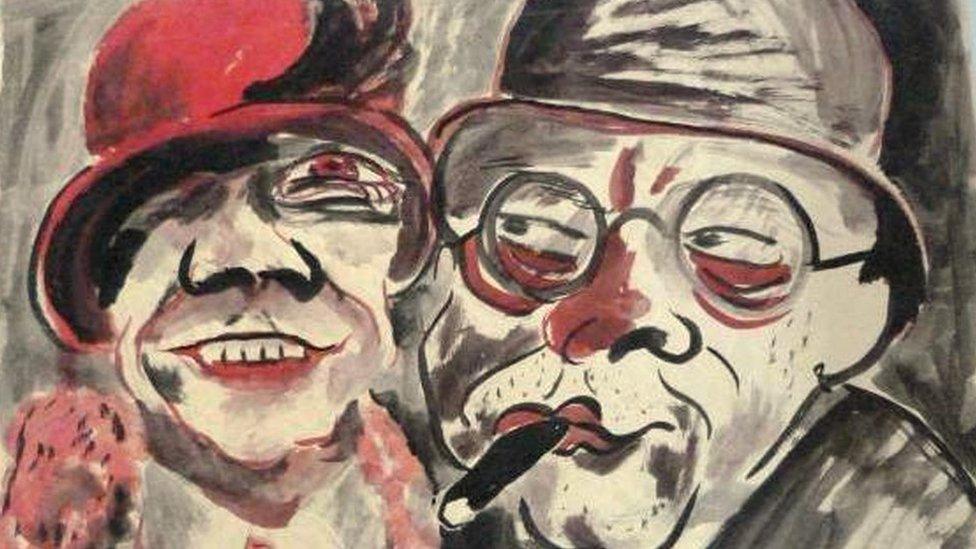

Claude Monet's painting of London's Waterloo Bridge is one of 1500 works with a baffling provenance

It's five years since authorities in Germany uncovered around 1500 works of art held by Cornelius Gurlitt, then aged 79. He'd inherited the work - by artists ranging from Old Masters to Picasso - from his father, an art-dealer who worked with the Nazis to acquire valuable artworks from Jewish families. Now exhibitions in Germany and in Switzerland are putting highlights on display, in the hope of alerting descendants who may be the rightful owners.

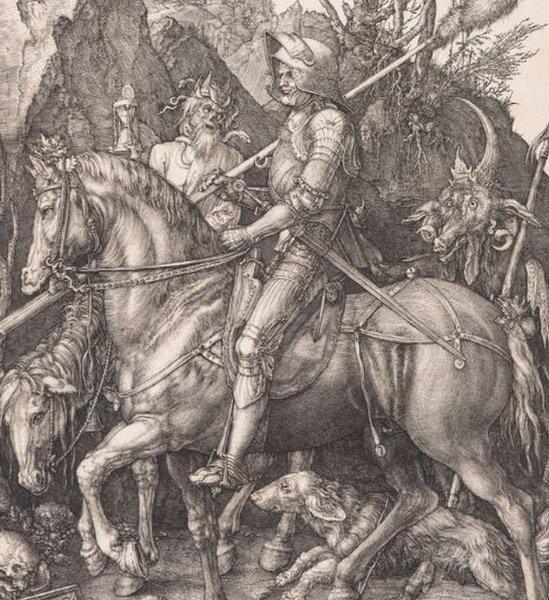

Gurlitt suddenly came to public notice in 2013, the German authorities had already known for a year that an astounding hoard of artwork had been found at his addresses in Munich and in Salzburg. The artists ranged from Picasso to Durer and Toulouse-Lautrec.

Initially, officials tried to keep the discovery secret. After all, Gurlitt appeared to have broken no laws. But a news magazine got hold of the story.

The collection had been inherited from Gurlitt's father Hildebrand, a major art dealer who died in 1956. Hildebrand served Germany's Nazi leadership in three ways: he helped acquire important works from Jewish families at prices well below their true value; he sold examples of so-called "degenerate art" abroad; he was involved in assembling pieces for the grand "Fuhrer Museum" planned for Linz in Austria.

Head-scratcher: Just when did Hildebrand Gurlitt acquire this Eugene Delacroix painting Oriental Horseman?

The works of art are often described as having been looted from Jewish families. But Rein Wolfs, director of the Federal Art Gallery in Bonn, says images of Nazi stormtroopers violently pulling paintings from walls are misleading.

"This was a long bureaucratic process forcing Jewish owners to sell artwork they owned. For some it became a sort of Departure Tax which meant they were permitted to leave the country for South America or wherever. Eighty years later the question is which parts of the Gurlitt hoard came from that source? It's a massively complex issue."

The Bonn exhibition is one of two running in parallel. The gallery in Bonn is showing 250 pictures which throw light on the insidious process of acquiring the art and on the stories of the rightful owners, many of whom perished in the Holocaust.

The other exhibition is in Bern in Switzerland. It focuses on the issue of "entartete Kunst", or degenerate art, which the Nazis wanted to wipe from German culture.

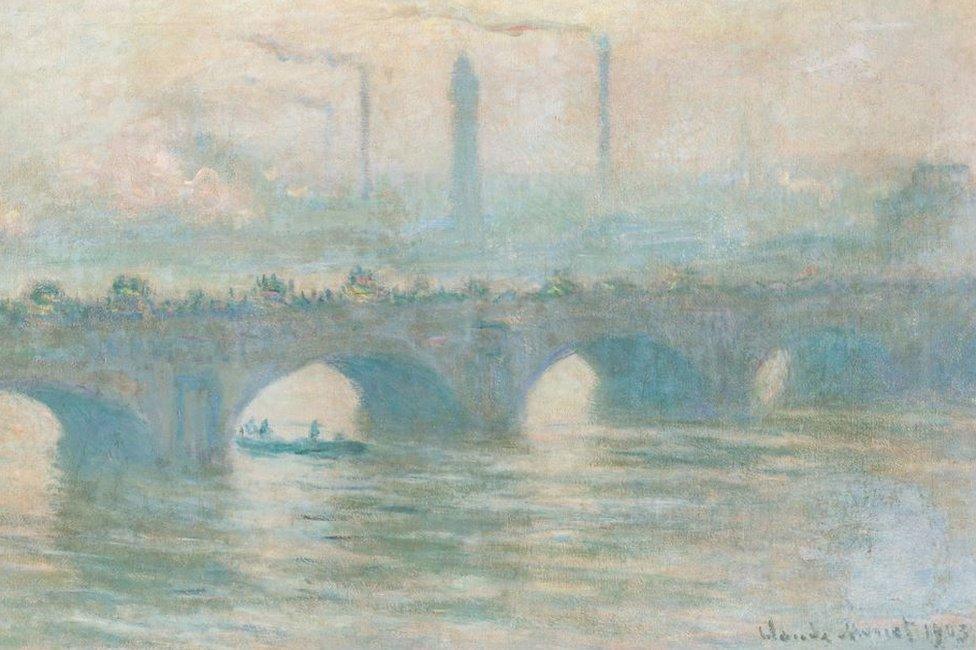

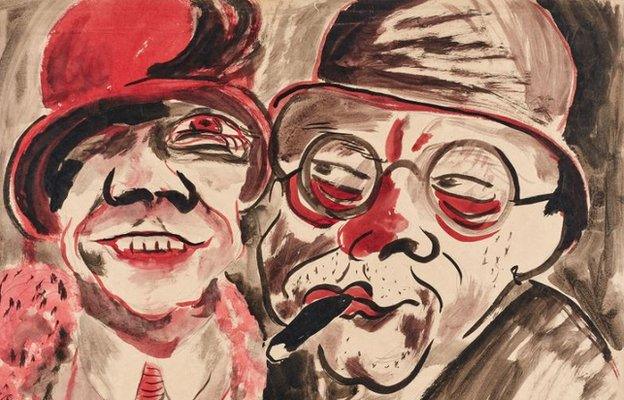

Hans Christoph's Couple is an example of a painting the Nazis considered against German values

Wolfs says that programme didn't, as people sometimes imagine, target only Jewish artists. "The Nazis wanted to remove all Modernist works from public galleries and museums: they held Modernism to be against German values. It was a ruthless attempt to eradicate what they mistrusted and hated and there's an obvious parallel with the Holocaust."

No one claims all 1500 works of art were acquired from Jewish families forced into selling: Hildebrand Gurlitt was an active art dealer for many decades. Walking around the exhibition in Bonn with Wolfs the complexity of discovering the provenance (ownership history) of each piece is clear.

Renoir's Still Life: If claimed, its background will be thoroughly investigated

"For instance we have a wonderful Monet painting of Waterloo Bridge in London, done in 1903. We have no direct indication it was ever a looted artwork. But we also have to be absolutely thorough and there is a weird detail: we know the mother of Hildebrand Gurlitt in 1938 wrote a note confirming that years before she had given him the Monet as a present for his wedding. But why did the mother even need to affirm that fact? - it seems odd and we are still investigating.

Wolfs points out a couple of smaller paintings by Eugene Delacroix, called Oriental Horseman. "They're another example of the problems we face. There are clearly deficits in our knowledge and we just don't know when they were bought by Hildebrand Gurlitt.

"Everybody expects that the team doing provenance research will come up with answers very fast. But in many cases the books are missing and whole archives no longer exist.

"It seems the Delacroix images are not under suspicion of being looted. But if somebody makes a claim we always investigate seriously. It's one of the main purposes of the exhibitions: we want people to make claims if they believe they are heirs of the rightful owners."

Stefan Koldehoff is a well-known German arts journalist who's written a book about the Gurlitt affair.

Albrecht Durer's Knight, Death and Devil

"At first the authorities in Germany did not handle the situation well: no one seems to have realised how enormous the story was. But eventually they saw this was a way to portray themselves as people who would do something good for Holocaust victims and for those who are still searching for the artwork."

Cornelius Gurlitt died in 2014 and bequeathed his collection to Bern. But Koldehoff says that, in doing so, he gave the German state a massive task.

"Germany has said it won't release works to Switzerland until every doubt about their history is gone. A whole team is working to achieve this. But as I understand it there are around 400 cases where it's proving very hard or impossible to come up with any answers.

"Only a handful of works have been restituted so far to descendants of owners from the Nazi time. So in the end I'm sure there will always be a remainder which present impossible questions of research. But the exhibitions are genuinely a way of trying to be transparent "

Gurlitt: Nazi Art Theft and its Consequences runs at the Federal Art Gallery in Bonn, Germany until 11 March 2018.

Gurlitt: 'Degenerate Art' runs at the Art Museum in Bern, Switzerland until 4 March 2018

Follow us on Facebook, external, on Twitter @BBCNewsEnts, external, or on Instagram at bbcnewsents, external. If you have a story suggestion email entertainment.news@bbc.co.uk, external.

- Published7 July 2017

- Published15 December 2016