Will Gompertz reviews Charles II: Art & Power ★★★★☆

- Published

There is something hauntingly contemporary about this exhibition.

It starts with a disgruntled England, which has made a cataclysmic decision to break with an imperfect but effective Europe-entwined institution that has been the basis for the country's social, economic, and political life.

We'd be better off without 'em, is the feeling.

The Irish and Scots are not so sure, but the will of a group of charismatic and self-righteous metropolitan politicians prevails, and people are warily readying themselves for a collective leap into the dark.

The population is divided on the matter, split like a pair of cheap trousers.

The fact is this scepter'd isle is going to be run differently from now on.

We stand poised. It is mid December. But we are not in 2017.

We are in 1649 and, like it or not, the country is going to be a republic. The old monarchical system along with its network of tactical intercontinental marriages is over. Oliver Cromwell and his New Model Army rule, OK.

Charles I, by Edward Bower, is the first painting in the exhibition

Which brings us to the first painting in the show where we meet Charles I shortly before his execution, commissioned, apparently, by Cromwell and his chums. The incarcerated King looks wizard-like, nonchalant, and inwardly majestic.

It is a respectful seated portrait suggesting the God-fearing Parliamentarian was uncomfortable doing away with a man widely believed to be hot-wired to God.

It didn't stop him, though. As we see in an explicitly detailed image called The Execution of Charles I. This gory print became an instant blockbuster; a bloodthirsty hit both at home and throughout an intrigued and amazed Europe.

Alongside it is a copy of a small book with a big title, Eikon Basilike: The Pourtraicture of His Sacred Majestie in His Solitudes and Sufferings.

This is important. It is basically a mix of memoire, prayer, and personal statement, probably - but not definitely - written by Charles I shortly before his public beheading at Whitehall.

What is certain is the date of its publication 10 days after the event, when it quickly became a bestseller and in-turn a cunning piece of beyond the grave Royalist propaganda.

Maybe the King wasn't so bad after all.

Maybe he was a martyr. And look at that lovely little woodcut image of him blessing his divine son as his chosen successor. The Restoration had begun in people's minds less than two weeks into the new Commonwealth.

The exhibition then jump cuts to 1660 and the return of the exiled Charles II.

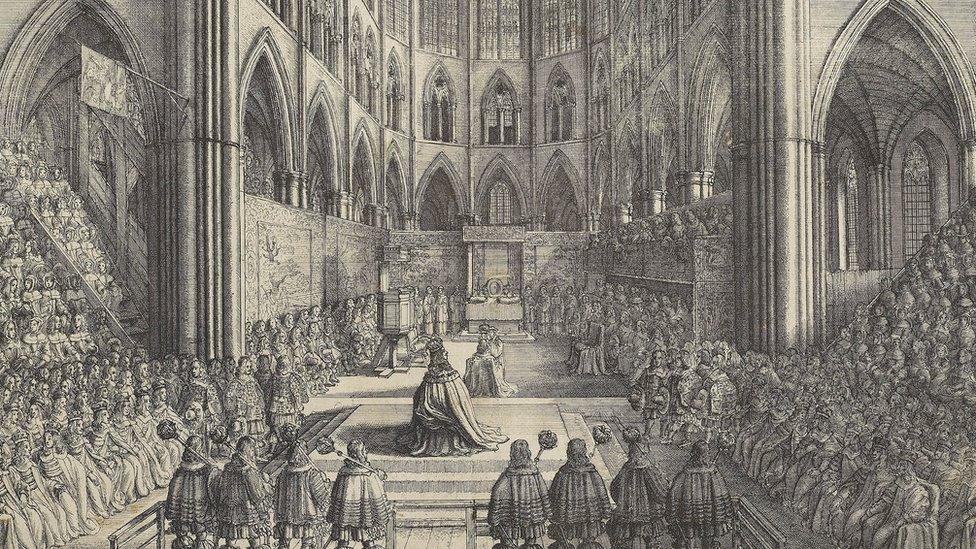

The Coronation of King Charles II in Westminster Abbey, by Wenceslaus Hollar

Backed with parliamentary cash, the soon-to-be crowned King has been out on a shopping spree to replace all the regalia and formal royal tableware Cromwell had melted down and flogged off.

It is a fine line the young man has to walk. His purchases need to be glitzy enough to impress and cement his status and legitimacy. But they can't be as flashy as the stuff his French cousin Louis XIV buys because: a) it might go down badly with the public and cost him his head, and b) he can't afford it.

He opts for silver gilt, which nearly 360 years later still looks magnificent. The craftsmanship and quality of the plates, candlesticks, chalices, and salts are impressive. As is an exquisitely embroidered bible given to the newly restored King, signalling a more liberal, post-Cromwellian, era.

The brakes are off. Theatres are re-opened.

Charles II, painted by John Michael Wright, is a powerful image of the monarchy restored

Charles II takes on a coterie of lovers (including the saucily depicted actress Nell Gwyn), and poses for a huge portrait by John Michael Wright.

What the painting lacks in terms of technique - which is quite a lot - it more than makes up for with size and visual impact. It is designed to establish the new King as the top man. We see him sitting in an elevated position, wearing the crown of state, and sporting his Order of the Garter costume under Parliament robes. He is holding his newly acquired orb and sceptre.

The idea is to hark back to Tudor and Elizabethan styles to imply stability through continuity. Frankly, he looks ridiculous; like an aging rock-star who has been allowed to rummage around in the royal dressing up box.

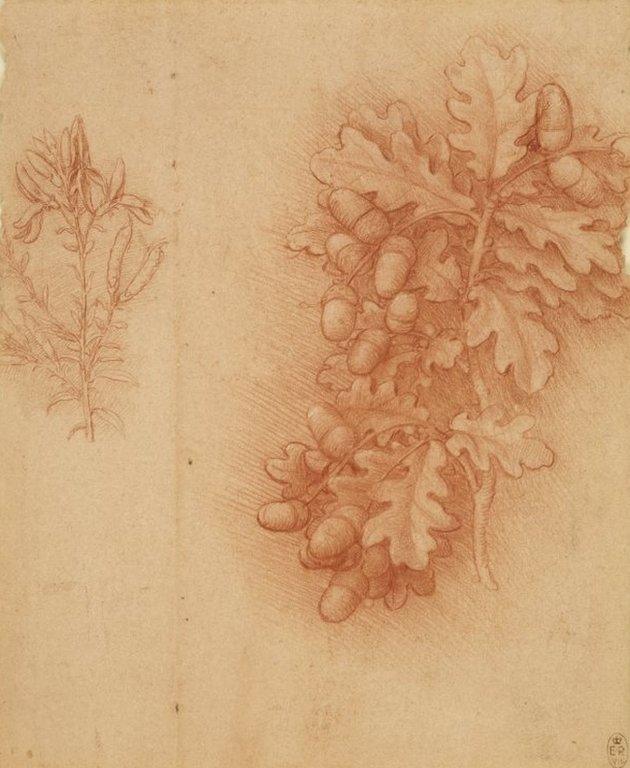

Leonardo da Vinci's Oak and dyer's greenweed, from circa 1505-10

It sums up what quickly becomes apparent in this show, which is Charles II was not blessed with the same curatorial eye as his late father. OK he acquired some wonderful drawings by Leonardo, Michelangelo and Holbein - some of which are on display.

But when it came to the task of retrieving the great paintings Cromwell sold off, or commissioning new pictures, he comes up short.

He did make a few decent purchases.

The Massacre of the Innocents by Pieter Bruegel the Elder

You'll see a very good Pieter Bruegel the Elder painting called The Massacre of the Innocents. Although, it is slightly odd in so much as there are no innocents being massacred.

There were originally, but when the Habsburg Emperor, Rudolf II, owned the painting he recognised the occupying troops as his own (specifically depicted as such by Bruegel, who was making a political point) and had all the dead babies painted out. The upshot is a scene in which women are bent over, crying their eyes out over loaves of bread and various poultry.

If you're after an exhibition stuffed to its royal gunnels with painterly masterpieces, the chances are you'll be underwhelmed by Charles II: Art & Power and should wait until January when the Royal Academy will do what he didn't and reunite much of his father's collection.

If, however, you are in the market for a richly told, thought-provoking history lesson that feels surprisingly relevant in today's Brexit Britain, with the added bonus that its central protagonist looks like Brian May from Queen, then you might consider the £11 ticket price as money well spent.

Charles II: Art and Power is at The Queen's Gallery, Buckingham Palace, London SW1A.