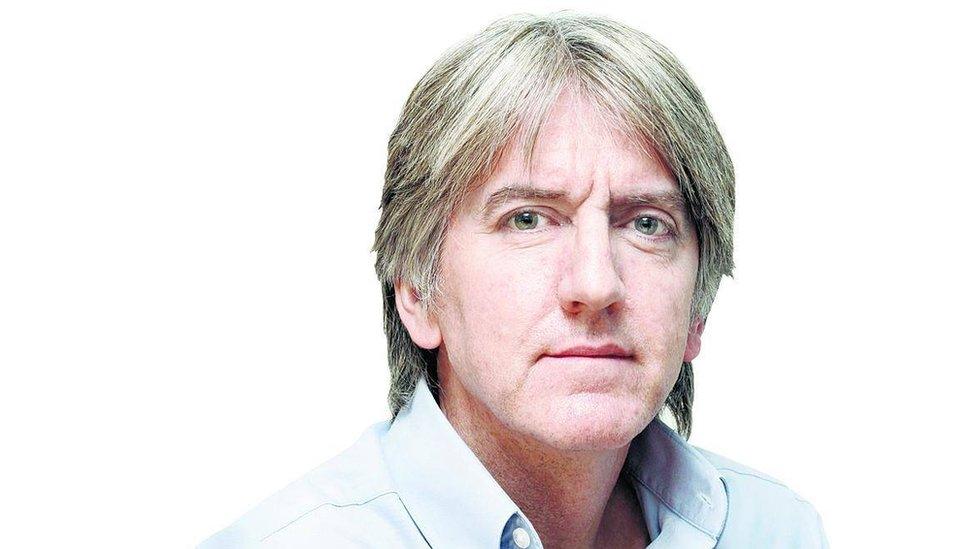

The late, great Steve Connor

- Published

Steve Connor was science editor at The Independent from 1998 to 2016

At 15.00 last Wednesday Steve Connor, a giant of British science journalism who over nearly four decades broke several of the biggest stories in his field and won the respect of an international audience, died after a long illness. He was 62.

For 18 years he was science editor of The Independent, going freelance when the print title closed last year. Before that he worked for the New Scientist, Daily Telegraph and Sunday Times.

Over the course of his years at the paper where I worked, Steve won so many awards it would be ludicrous were they not deserved, and pulled off the very rare trick for a reporter of being both better than his Fleet Street rivals at the stories they covered, and able to own several huge stories that nobody else knew about. Yet when Steve put them into the public domain, they quickly became international sensations.

Of the issues that he did most to advance, revelations about gene-editing technology, sex-selective abortions, meat grown in labs, and the discovery of the Higgs boson were among the many which everyone in the trade knew he had a peerless grasp on.

Warrior for truth

On climate change, he and Michael McCarthy, The Independent's erudite environment editor, made that story central to the news agenda fully years before others gave it the same attention. Simon Kelner, the long-serving Editor of the paper, knew that he had a huge asset in his science editor, whose stories had such editorial integrity and exciting potential that they would often be the best read on the paper's website.

Indeed, editors and news editors alike would look to him when they desperately needed a splash. It is instructive that when Roger Alton re-launched the paper as editor, his first front page was a Steve special, on "The Methane Time-bomb". And similarly, when I re-designed the paper as editor, it was always going to be Steve who had the byline on page 1, this time on "The next genetic revolution."

Steve could be obstinate, but never in service of his own ego, and always - always - in service of the truth, for which he was a warrior. If a section editor or executive asked him to document some sizzling new discovery, it often fell to him to explain that actually this was an old story, or the science wasn't quite there, or the implications were still too unclear to be jumping up and down about. He did so in plain English without being patronising. It meant that when he said he had a big story, it lifted the whole office.

A private man who commuted in from Hertfordshire, his silver hair was arranged in curtains, and he had the admirable habit of re-arranging it away from his forehead when deep in thought. He deployed this technique when explaining the latest developments in his prostate cancer, or telling anecdotes about his time as a student of Richard Dawkins while at Oxford.

As Jeremy Laurance, the esteemed former health editor of The Independent who sat opposite Steve for a decade, put it in this beautiful obituary, external, "He had huge scientific knowledge, rare insight and the doggedness necessary to get to the bottom of things, allied to the small boy's love of chucking things from the back of the class. But he was meticulous, too, and abhorred hype. The essential ingredients, in other words, of a brilliant journalist."

A servant of science

Journalism has many functions, from the scrutiny of those in power, to the provision of popular entertainment and the supply of labour to those too chaotic to get jobs elsewhere. Other, less widely appreciated uses of the trade include explaining complex issues in simple language, and chronicling the accretion of material Knowledge, which by our common effort grows, as opposed to moral Knowledge, which despite our common effort doesn't.

The first kind of Knowledge is also called Science, and it isn't overstating things to say that Steve dedicated his career to the belief that in Science - and in the countless patient hours of experimentation by unsung heroes that caused it to advance - much of the best hope for humanity found its repository.

Some people think that the authority of Science comes from its refusal to mix with the tawdry business of morality; but for Steve it was precisely the moral power of Science to improve lives, and to shape the future, that made it worth explaining. Like most journalists, his work will have touched countless people that he never met; unlike most journalists, it had an intellectual and editorial pedigree that were never, ever, in doubt.

He really was the best of his generation, a treasured colleague, and a giant of British science journalism whose loss diminishes Britain, science and journalism itself. In his humble, persistent way, he fought for the truth in an age when it was becoming less fashionable. His work and inspiration will long outlast him, and I commend his spirit to the living.