Max Clifford, king of fake news

- Published

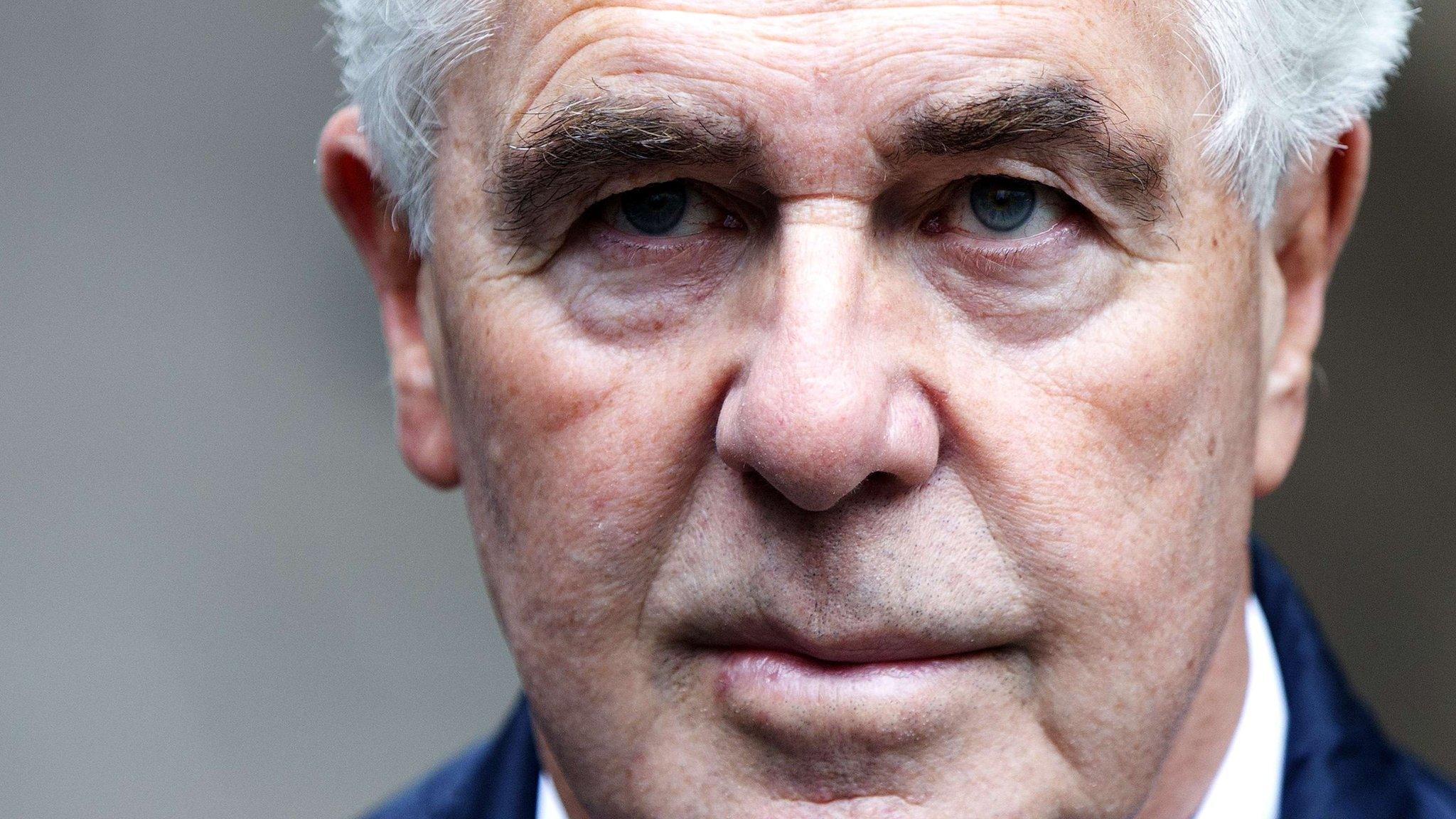

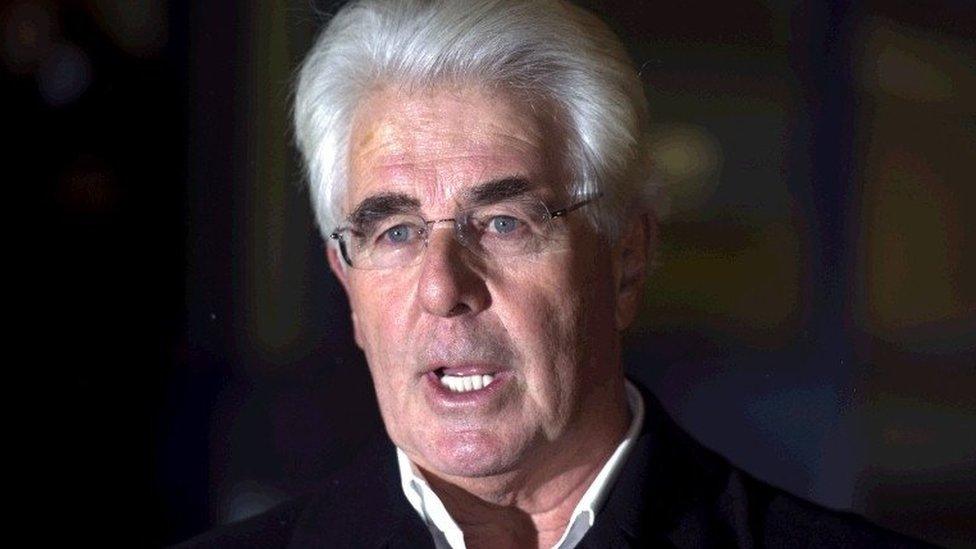

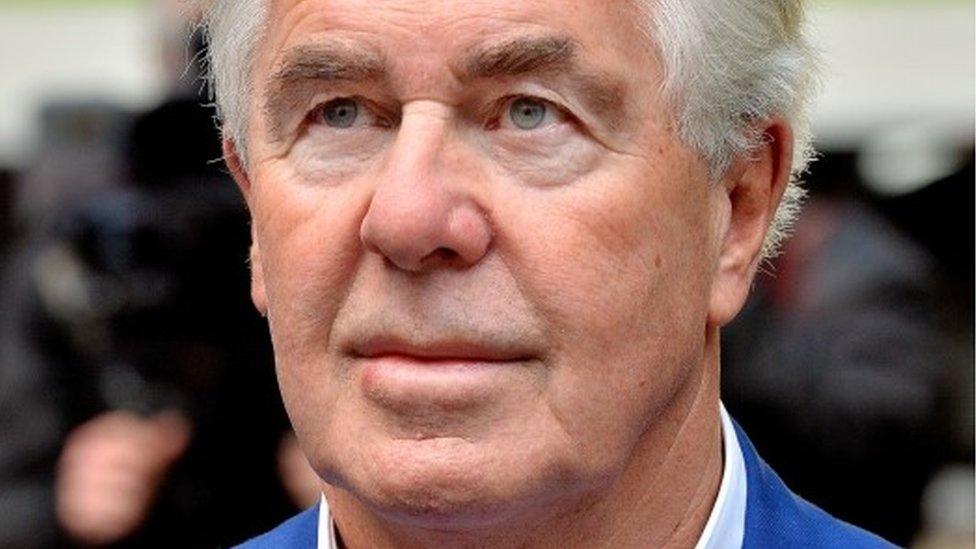

Photographers surround British publicist Max Clifford as he leaves Westminster Magistrates Court in 2013 where he entered not guilty pleas after being charged with 11 counts of indecent assault

To write this anecdotally charged blog about Max Clifford, the celebrity publicist and convicted sexual predator who died yesterday, is to contravene two conventions that he would have little time for himself.

The first, brilliantly parodied by Private Eye in their "The [insert famous name] I knew" and "Farewell, then [insert famous name]" skits, is that treating someone's death as an opportunity to parade your own dealings with them is the very height of vanity. The second is that we do not speak ill of the dead.

Alas that second convention is often motivated by the desire among bad people to protect their legacy, and in fact we should speak of the dead as we speak of the living: that is, judiciously. As for the first, well, it is always a privilege to be of interest to Private Eye.

Max Clifford was an ambassador for a vanished era who used his journalistic nous, courage, and sheer malice to become a giant of post-war British culture. Not bad, you might argue, for the son of a Surrey electrician addicted to gambling and alcohol, and a mother - described by her son as "fat, jolly and flatulent"- who on occasion pawned her wedding rings so that the family might be fed.

For all that tough upbringing, and for all the work he did for charities and indeed his reportedly exemplary raising of his daughter Louise, who had a disability, at its core Clifford's dealings were, like Iago's, driven by one thing - filth.

'Good honest filth'

Clifford died after being taken ill in prison, where he was serving eight years for the sexual abuse of women and girls as young as 14. He was appealing against all of his convictions, and told all who asked that he was confident of clearing his name. This point has been widely reported, as has the fact that much of the trial centred on the length of his penis, and his boasts thereof.

Less widely reported is a point made by the presiding judge, who said that had the offences taken place after 2003, when the law changed, he would have been tried for rape.

As a reporter many years ago, I called him on several occasions to corroborate stories. (I never, as far as I can remember, dealt with him as an Editor). It is a curious fact that every single one of the perhaps dozen conversations we had on the phone proceeded by the same trajectory.

Clifford would be in his house in Surrey. We would exchange pleasantries. I would say I had a story concerning some individual he represented. He would listen attentively, it seemed - then say he couldn't talk about the subject, either because he had signed a hugely lucrative contract with a tabloid, or was about to. Then, like a master novelist - and Clifford was nothing if not a legendary story-teller - he would drop a hint that, actually, there was something he could perhaps mention to me.

This ability to make journalists feel special, and that they are getting morsels of information nobody else knows, is one of the most important skills a PR can have, and Clifford was supreme at it.

After mentioning he might be able to talk about the subject at hand, he would always - always - make me hold the line for three of four minutes, as he wandered round his Surrey home attending to some domestic matters. I once heard him ask a workman if he wanted jam on his toast. Another time, I remember him asking for a kettle to be turned on; and once he said something inaudible to a person cleaning his car.

This delay was designed, of course, to heighten the anticipation for his interlocutor. A junior reporter - indeed, this junior reporter - would think 'Blimey, Max Clifford is about to give me a story'. Instead, with what became totally predictable intonation, he would pour poison in my ear, almost always about women.

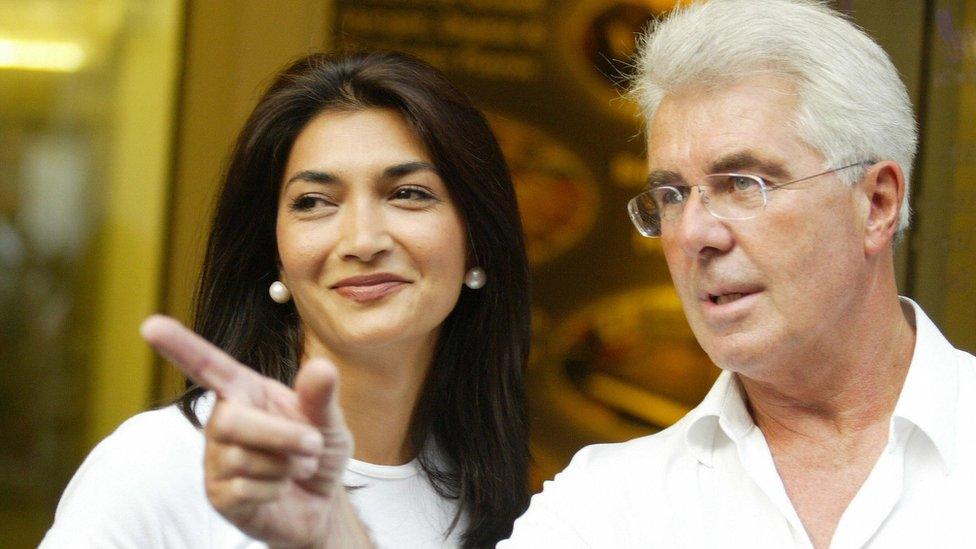

Max Clifford negotiated with tabloid newspapers on behalf of Faria Alam. The former secretary at the Football Asociation revealed her affair with with England Football Manager Sven Goran Eriksson.

Clifford would preface every single sentence with "Off the record", before saying something vile about a public figure on the wrong side of him. I heard him be abusive about Sharon Osbourne. I clearly remember he called both Faria Alam, who he was representing after her affair with Sven Goran Eriksson, and Victoria Beckham "slut".

That was after he sold the story of an alleged affair between David Beckham and Rebecca Loos to the News of the World. Amazingly, he later claimed that if Beckham had come to him first, he would have killed the story by telling him to lend his phone to a friend, who would have been paid to lie that he had sent the incriminating text messages.

Time and again, his messaging to me, a junior reporter, was about women being unclean, or cheap. Like Donald Trump, another boastful sexual predator, he seemed fanatical about the idea of female purity. Trump referred to an interviewer's menstruation. With Clifford, the talk would often turn to vaginas and clitorises.

I never met the guy. But I wasn't surprised to read him describe, in memoirs that shamelessly chronicled his sexual exploitation of vulnerable people, that the sex parties he organised for celebrities in the 1960s and 1970s were "good honest filth".

Hypocrite

This is the context in which to see the ludicrous claims that he made on behalf of his own public service. Clifford raised money for charity and the profile of several charities. But given he was a compulsive liar, it is hard to know precisely how much he did, and for whom. What we do know is that most of the claims he made for himself were absurd, and render him a hypocrite.

Clifford claimed to be a lifelong socialist. But he made millions of pounds by exploiting people often desperate for money. He deluded himself that it was his story about the Tory MP David Mellor having sex in a Chelsea kit (a lie) that tarnished the Tories' reputation for probity. In other words, that by associating them with sleaze, he got them out of government. But Clifford's motivation wasn't cleaner government - it was a bigger pay cheque, for himself.

He claimed to be a champion of women's dignity, giving a voice to the voiceless and ensuring that their story was heard. But he died in jail after being convicted of sexual abuse, in crimes that were they committed later might have been considered rape.

And just as he pretended, with his Surrey socialist credentials, to be a friend of the poor, so Clifford pretended to be a great ally of British journalism, feeding it with countless stories that titillated the masses and rescued them from the quotidian tedium of their otherwise miserable lives.

But by promoting lying on an industrial scale, Clifford was in fact an enemy of the most fundamental values any proper journalist should hold dear, and did more than most to create the culture of distrust toward the media which now corrodes our democracy.

Liar, liar

It would be hard to overstate the extent to which Clifford grew wealthy by making stuff up. At least he acknowledged it.

"I learnt early on that by colouring [adding spicy details to stories], you get the big coverage… I was always instinctively good at lying," he once said. Another time, he told the Oxford Union, "Every day, every week, every month, a lot of the lies you see in newspapers, in the magazines, on television, on radio, are mine."

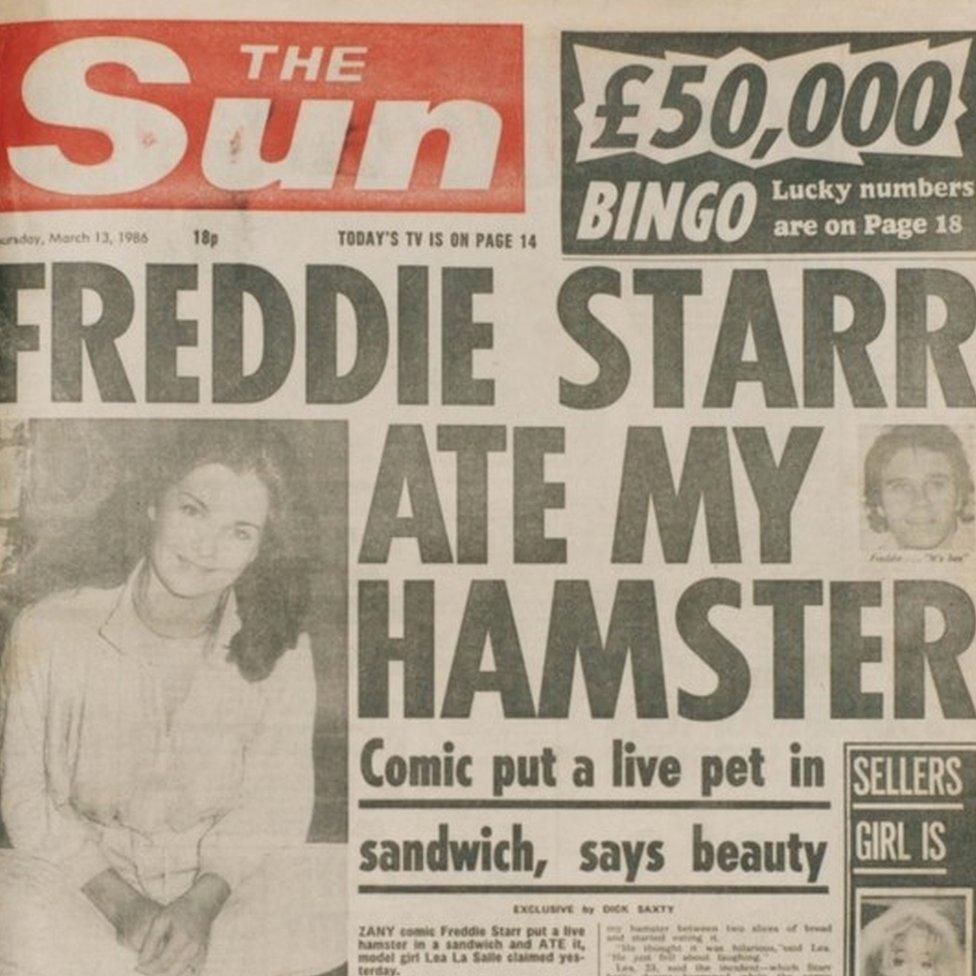

The Sun's Freddie Starr 'scoop'. It turned out the story was a hoax.

He claimed, falsely, to have been instrumental in launching the Beatles. Freddie Starr obviously never ate the notorious hamster owned by his girlfriend. Derek Hatton, the Militant socialist, didn't have an affair with the actress Katie Baring. The list of Clifford's lies goes on, and on. And on and on.

Why does this matter? If millions are entertained through scurrilous tales, and the only cost of it is a few pompous celebs lose their shine, or marriage, so what if the Max Cliffords of this world get rich along the way?

That would be a naïve and dangerous way to understand the culture he represented.

We are living through a crisis of trust in many of our institutions - not least the media. This has been accentuated by the phenomenon of fake news, which though it's nothing new, has heightened suspicion that journalists are crooks.

The crisis of trust in media is largely the fault of journalists, who have made a habit of missing big stories, and who still fail to speak for many of the disenfranchised and alienated. But it has other causes too, from technology, which makes it easier to disseminate lies to a vast audience in just a few seconds, to an erosion of the cultural value of truth.

One reason fake news isn't a bigger phenomenon in Britain is that we've had "post-truth" for decades - for as long as Clifford has plied his trade, and even before.

It naturally seems pompous, self-regarding, even a bit twee for journalists to harp on about the importance of truth, as if not just our careers but our lives depended on it. Yet a civilised society cannot proceed unless there are commonly agreed facts. That can only happen if untruths are weighed against the available evidence.

For Clifford, however, evidence was a costly distraction. He spent his entire career fabricating stories in service not of truth, or justice, but his own bank balance. In that way, he helped create a culture in which you could boast "don't believe everything you read" - and be right to say so, because liars like Clifford were preying on your attention.

The culture around Clifford is gone too, of course. Tabloids still have huge power, but with diminished readerships in print, they aren't the force of yore, and their online versions face unprecedented competition.

And since the Leveson Inquiry, kiss-and-tell celebrity stories are less prevalent. Clifford knew that, like all geniuses, his career and talents were perfectly aligned with the emergence of a culture that he came to personify.

We're not meant to speak ill of the dead. But if you believe in journalism, the integrity of the public domain, or the very idea of truth at a time when it is becoming unfashionable, you have to see that in this supposed king of spin you had a lifelong enemy. And that's assuming you're not one of the women he exploited sexually as a teenager.

Max Clifford was no friend of journalism.

- Published10 December 2017

- Published10 December 2017

- Published2 May 2014