The tragedy that inspired Zombie - The Cranberries' biggest hit

- Published

Allow YouTube content?

This article contains content provided by Google YouTube. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read Google’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

"This song's our cry against man's inhumanity to man; and man's inhumanity to child." - Dolores O'Riordan.

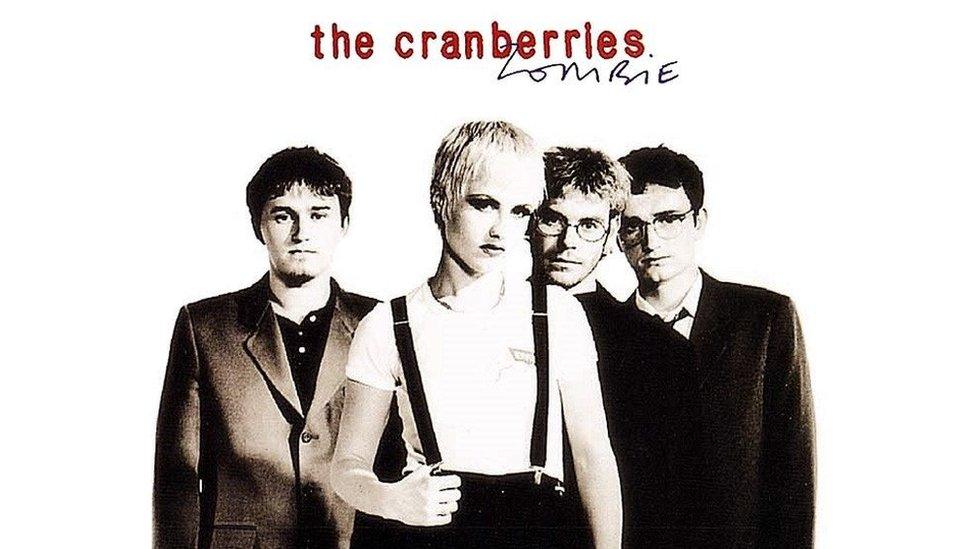

After The Cranberries' debut album, people thought they had the band sussed out. The Limerick band were part of the Celtic rock tradition, their shimmering, sorrowful ballads brought to life by Dolores O'Riordan's bell-clear vocals.

Zombie shattered that illusion.

A seething condemnation of the IRA, it was backed by pummelling, distorted guitars while O'Riordan's lilt was contorted into a primal howl: "What's in your head Zombie? Zomb-ie-ey, ay-ey, ay-ey, aooowwwww."

Her pain was real: Zombie was a visceral response to the death of two children in an IRA bombing in the Cheshire town of Warrington.

Three-year-old Johnathan Ball was killed when two bombs hidden in litter bins detonated on a busy shopping street in March 1993. Tim Parry, aged 12, died five days later.

The Cranberries in 2012 (L-R): Noel Hogan, Fergal Lawler, Mike Hogan and Dolores O'Riordan

O'Riordan, who was on tour at the time, found herself deeply affected by the tragedy.

"I remember seeing one of the mothers on television, just devastated," she told Vox magazine in 1994.

"I felt so sad for her, that she'd carried him for nine months, been through all the morning sickness, the whole thing and some… prick, some airhead who thought he was making a point, did that."

The singer was particularly offended that terrorists claimed to have carried out these acts in the name of Ireland.

"The IRA are not me. I'm not the IRA," she said. "The Cranberries are not the IRA. My family are not.

"When it says in the song, 'It's not me, it's not my family,' that's what I'm saying. It's not Ireland, it's some idiots living in the past."

The Warrington bomb, which targeted a busy shopping street, shocked the UK

Her anger and frustration poured into the song - which she wrote alone in her flat in Limerick on an acoustic guitar, before toughening it up in rehearsals.

"I picked up the electric guitar. Then I kicked in distortion on the chorus, and I said to Ferg [Fergal Lawler, drummer]: 'Maybe you could beat the drums pretty hard?'" she told Team Rock last year, external. "Even though it was written on an acoustic, it became a bit of a rocker."

The heavier sound was the "right thing" for the song, said guitarist Noel Hogan.

"If it was soft, it wouldn't have that impact," he told Holland's FaceCulture in 2012, external.

"This was a new direction for us. And it would stand out in the set because of that."

The single was recorded in Dublin's Windmill Lane studios

Released in September 1994, Zombie went on to become the band's biggest-selling single, reaching number one in Germany, Australia and France; and topping the US alternative rock charts.

O'Riordan's lyrics received some criticism at the time. People called her naive and accused her of taking sides in a conflict she didn't understand.

"I don't care whether it's Protestant or Catholic, I care about the fact that innocent people are being harmed," she told Vox. "That's what provoked me to write the song.

"It was nothing to do with writing a song about it because I'm Irish. You know, I never thought I'd write something like this in a million years. I used to think I'd get into trouble."

Instead, the song became an anthem for innocents trapped by other people's violence.

In the 1990s, O'Riordan would regularly dedicate it to the citizens of Bosnia and Rwanda; and her message applies equally to recent attacks in Manchester, Paris and Egypt, to name just three.

"It doesn't name terrorist groups or organisations," she told the NME in 1994, external. "It doesn't take sides. It's a very human song.

"To me, the whole thing [terrorism] is very confused. If these adults have a problem with these other adults well then, go and fight them. Have a bit of balls about it at least, you know?"

BBC ban

In the UK, the song reached number 14 in the charts - its success perhaps hampered by the BBC's decision to ban the video.

The original was shot by Samuel Bayer, who had previously directed the videos for Nirvana's Smells Like Teen Spirit and Blind Melon's No Rain.

He travelled to Northern Ireland and shot footage of the troubles, including images of children holding guns, which the BBC (and Ireland's national broadcaster RTE) objected to.

Instead, they broadcast an edited version focusing on performance footage, which the band disowned.

"We said it was crap but knew we were fighting a losing battle," Hogan told New Zealand magazine Rip It Up in 1995. "It's just really stupid."

The official version of the video endured, though. It has been watched more than 660 million times on YouTube - making it the site's 210th most-popular video of all time.

The singer was described as "a true artist" by her bandmates.

The song also remained a highlight of The Cranberries' concerts, regularly acting as the closing number of the set. The band recorded an acoustic, stripped-down version for last year's Something Else album.

There's also a 1995 Eurodance cover version, external (awful, naturally), while Eminem sampled the song on his latest album.

US metal band Bad Wolves had also been due to re-record the song with O'Riordan this week but the singer was found dead in her hotel room hours before the session was due to take place.

"We are devastated," said The Cranberries in a brief statement.

"She was an extraordinary talent and we feel very privileged to have been part of her life. The world has lost a true artist today."

The father Tim Parry also paid tribute, after learning for the first time that Zombie had been inspired by his son.

"The words are both majestic and also very real," he told BBC Radio Ulster.

"To read the words written by an Irish band in such compelling way was very, very powerful."

And perhaps that message of defiance and solidarity will be O'Riordan's legacy.

"If you feel really strongly about something and it really annoys you, then other young people will think the same as you and something can be done about it," she once told the NME.

"But first, you have to be aware."

Follow us on Facebook, external, on Twitter @BBCNewsEnts, external, or on Instagram at bbcnewsents, external. If you have a story suggestion email entertainment.news@bbc.co.uk, external.

- Published16 January 2018

- Published16 January 2018

- Published23 January 2012

- Published24 February 2016