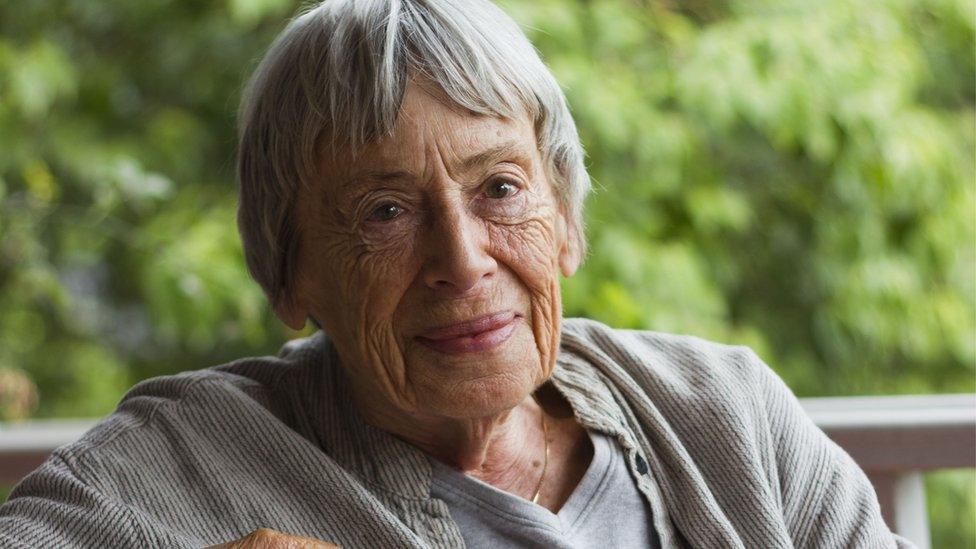

Ursula K Le Guin: The 'fearless' author who showed us a different world

- Published

Ursula Le Guin was loved for her groundbreaking fantasy novels that tackled questions of gender, race and the environment.

She influenced generations of authors from Margaret Atwood to Neil Gaiman - and wrote about a boy wizard 30 years before Harry Potter.

In her writing and in her life, Ursula Le Guin refused to blindly accept how the world is supposed to work.

In life, if something was illogical or unjust, she simply decided that things would be different.

"I am a man," she said in a 2015 BBC Radio 4 documentary, somewhat surprisingly.

"When I was born, there were actually only men. People were men."

Le Guin, who was born in 1929, meant people who mattered were men, and that women were as near as invisible. So she decided to bestow upon herself the power that was more often afforded to men.

"I am a man, and I want you to believe and accept this as a fact, just as I did for many years," she wrote, external.

In that same documentary, Neil Gaiman summed her up by saying: "She is willing to change the landscape of your head with her ideas and there's such power in that. It is that power of, things could be different."

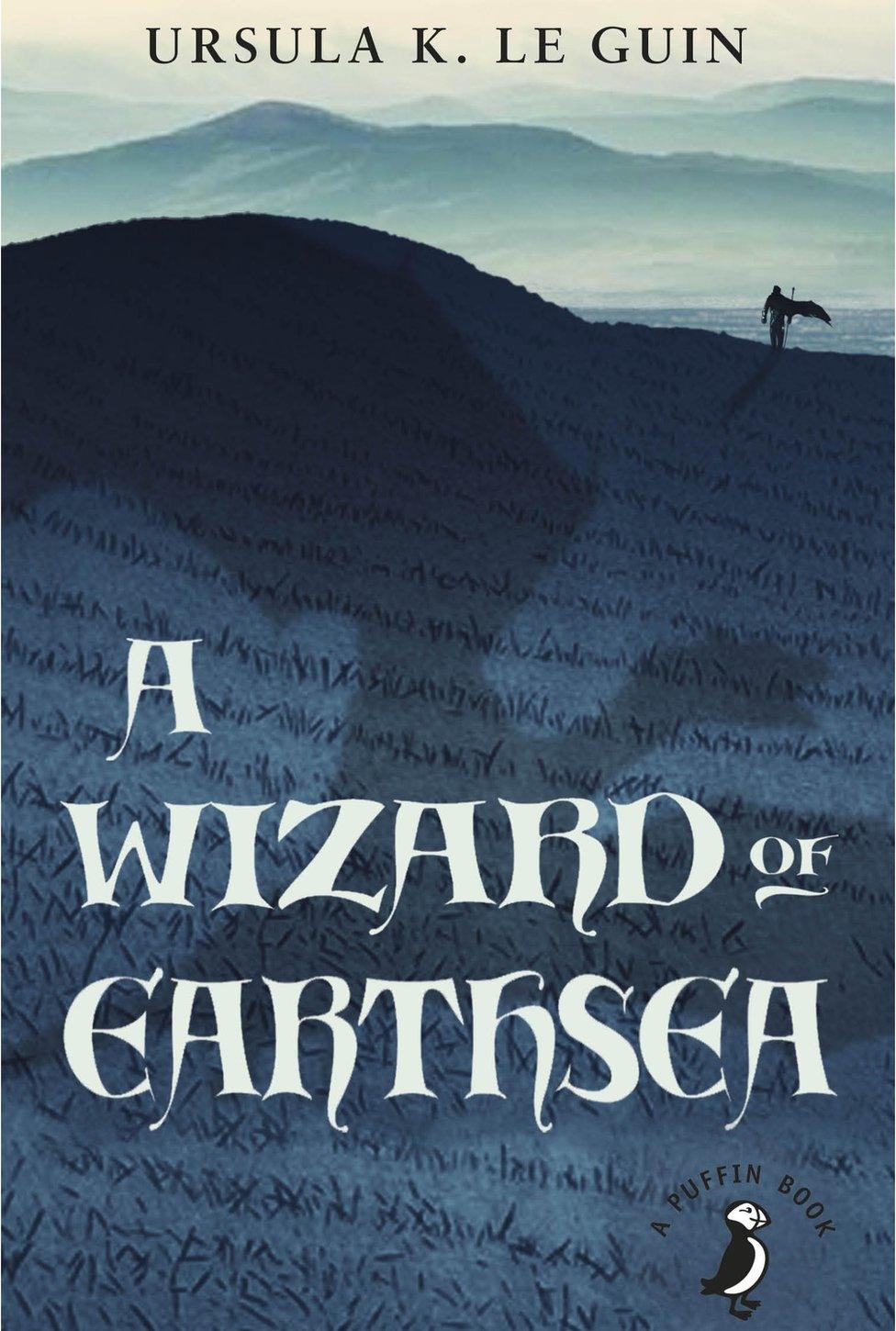

In her writing, Le Guin created new worlds to show us how things could be different - from the glacial, genderless society in The Left Hand of Darkness to the magical, racially diverse island setting of Earthsea.

She was "a fearless writer, a fearless woman, who really gives courage to writers and gives courage as you read her", fellow author Una McCormack told the BBC on Wednesday after Le Guin's death at the age of 88 was announced.

'What it means to be human'

Such worlds "give her a space to explore ideas of what it means to be human, [with] different social arrangements", McCormack said.

"She was a very political and socially savvy writer, and these gave her imaginative spaces in which to explore different ways in which human beings can relate to each other."

Writing in The Guardian, external, Margaret Atwood said: "In all her work, Le Guin was always asking the same urgent question: what sort of world do you want to live in?

"Her own choice would have been gender equal, racially equal, economically fair and self-governing, but that was not on offer."

Author China Mieville, who interviewed Le Guin for Radio 4 for her 80th birthday in 2009, said he first read her Earthsea books when he was approaching his teenage years.

"They were and remain incredibly influential for generations," he told BBC News. "They were also some of the first books I remember returning to again and again.

"There was absolutely no sense of being spoken down to or some kind of special or slightly diluted literature for younger readers. These were written with a great tone of ethical seriousness and a very powerful, controlled, but moving prose, and a great humaneness which never veered into sentimentality.

"As you get older and return to those books and read some of her other books, I started to realise other things, and started to sense this slow-burning fury at injustices and a very sharp and unremitting diagnosis of things in the social world, always allied to this humaneness."

'Unendingly moving'

A Wizard of Earthsea, about a boy who went to a school for wizards, was the first in the series and was published in 1968. She wrote a further five Earthsea books, the last of which came out in 2001.

The later books revisited and revised the setting, with Le Guin taking into account feedback from readers with "a tremendous capacity for self-criticism", Mieville said.

"I don't know a single other writer who's done anything comparable and I find it unendingly moving."

Her influence on later writers is such that Mieville said she changed the way he sees the world. "It's a kind of writing that sits so close to you that it's like spectacles."

In person, interviewing her for the radio documentary, the author was "a delight", Mieville said.

"She absolutely would not hold back on her opinions when she didn't think things were right," he added.

"She didn't suffer fools gladly, but that's not code for 'She was difficult or unpleasant to be around.' She was an absolute delight and whip smart and very funny."

Her stance towards "fools" can be seen in her reply to a request for comment to promote an all-male sci-fi anthology. She refused, signing off: "Gentlemen, I just don't belong here."

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

She also didn't hold back when talking about a 2004 mini-series adaptation of Earthsea, which, among other things, made most of the characters white.

"Right there, they betrayed something very deep in the book," she said. "It was a terrible movie. But I was kind of glad it was a terrible movie because it had so little to do with my book."

Le Guin was often dismissed as "just" a science-fiction or fantasy writer, but admirers knew she was much more than that.

Una McCormack said her works should be considered "world class literature".

"I think it's a real shame that she was never given the Nobel [Prize for Literature]," McCormack said. "Her reach, her skill, her style is that good."

Le Guin herself told The Paris Review, external: "Where I can get prickly and combative is if I'm just called a sci-fi writer. I'm not. I'm a novelist and poet.

"Don't shove me into your damn pigeonhole, where I don't fit, because I'm all over. My tentacles are coming out of the pigeonhole in all directions."

Afraid of being forgotten

One of her fears, the author told Mieville on Radio 4, was that her work and legacy wouldn't last once she's gone.

"Why do all women writers get forgotten extremely quickly?" she asked. "That's a real anxiety simply from watching what happens to women writers. They go much faster than men writers do."

So, yes, she was a woman after all.

But she succeeded in rising above all questions of gender and genre and ensured that the worlds she created will continue to be visited by readers, who may not see things quite the same way again when they come back down to Earth.

Follow us on Facebook, external, on Twitter @BBCNewsEnts, external, or on Instagram at bbcnewsents, external. If you have a story suggestion email entertainment.news@bbc.co.uk.

- Published24 January 2018