W1A stars head to Sheffield with The York Realist

- Published

Ben Batt (left) and Jonathan Bailey star in The York Realist

Actors Jonathan Bailey and Ben Batt have put TV careers on hold to appear in Sheffield in a new production of a play some consider a modern classic. The York Realist is a gay romance set in 1960s Yorkshire, when homosexual acts were still illegal. If the play lacks a traditional happy ending, says writer Peter Gill, that's because life seldom supplies them.

Last year Ben Batt and Jonathan Bailey narrowly missed sharing screen time in the third series of the BBC comedy W1A.

Batt appeared as a cross-dressing footballer, while Bailey returned to the role of ambitious production assistant Jack, who realises he's losing the battle for the affections of colleague Izzy.

But now on stage in The York Realist, they share scenes of aching intensity as two gay men in the England of the early 1960s.

Batt is the farmer drafted in to play a centurion in York's medieval Mystery Plays. Bailey is an assistant director up from London who spots George's talent as an actor and falls for him.

Bailey played Jack (centre) in W1A, usually seen battling for the affections of Izzy (left)

Peter Gill's play was first seen in 2001. The new production has been at the Donmar Warehouse in London and is now heading to Sheffield's Crucible theatre, a venue four times as big.

Batt says the cast discussed in rehearsals how different Britain feels in the play compared to today.

"The obvious thing is that it was illegal for my character George to go to bed with John - the law didn't change until 1967. But Peter Gill is too good a writer to make that his only point," he tells the BBC.

In the play, audiences sense that two people who are meant to be together struggle to find a future they can share. But the era's draconian laws on sexual morality don't wholly explain the men's hesitation.

Batt says the cast also discussed farming in the 1960s and speculated which films and music and fashions the characters would have been familiar with.

"I think audiences are left thinking about the contrast between the life of 1960s rural Yorkshire and the very different metropolitan life which John represents. And maybe that division hasn't altered so very much and we're seeing the effects even today."

He is keen to find out if that discussion will feel different when played to a Yorkshire audience.

"I'm actually from Wigan so it's a different part of the north. But in many ways the family remind me of my own. And Peter makes sure the women are as important and well-drawn as George and John are."

Bailey says the play is a rich experience, in part because his character John unexpectedly turns out to be less comfortable in his own skin than George is.

"These two men deal with their sexuality in very different ways. John is exposed to a metropolitan understanding of what gay culture was in the early 1960s. I think it's a very lonely existence for him being part of that culture, even though theoretically it was more progressive than in the north.

"The narrative of what it is to be a gay man was put onto John and he brings that to York. But then he meets George and sees someone who's inherently understanding of himself and of his own emotions.

"So there's a conversation there which is still very relevant and I think probably has been taking place for the past 50 years. If you carry around the political arguments with you - does that help you feel happier within yourself or does it push you further away from your true instinct?"

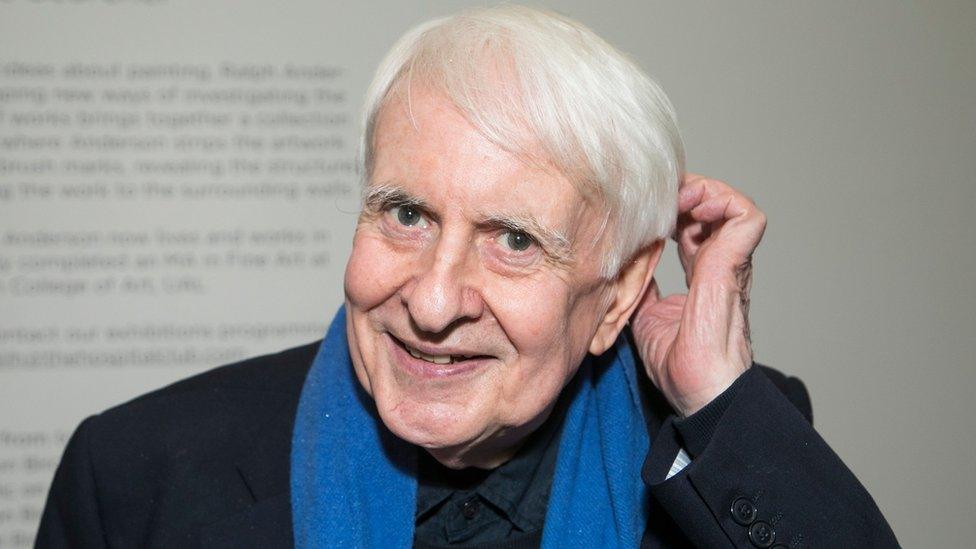

Peter Gill says there's been a "huge move forward" in audience reaction to gay romance

Peter Gill says he tries to avoid the label he's sometimes given of gay playwright.

He's had an unusually varied career as writer and director - you can even catch him as a young actor in the 1964 film Zulu. At 78, he's in danger of becoming a Grand Old Man of British theatre.

"A lot of what I write is about class - an unavoidable topic in British theatre as it is in British life," Gill explains.

Though he was starting out as a director in the 1960s, he says The York Realist isn't really about his own life at the time.

"Perhaps all young people think they're living through a period of change. But I think it's true that from the beginning of the 1960s we sensed reform was coming, not only relating to sexuality. But I think the decade has been so mythologised that it's difficult to know now what's myth and what was the truth.

"People of my generation had been in our adolescence when David Maxwell Fyfe (Home Secretary from 1951) set out to persecute gay men. The treatment meted out to people like Peter Wildeblood and Michael Pitt-Rivers meant it was not a good time to be a 14-year-old and gay.

"My play gives a fairly roseate view of the situation for gay men before 1967. These things are mainly unknown now to young people. But since we're engaged in a huge discussion these days about people being isolated and abused, perhaps we should recall how things were when I was young."

The play's director is Rob Hastie, who's also the artistic director of Sheffield Theatres.

"Peter wrote one of the first great plays of the 21st Century so I was keen to revive it," he says.

"Even aside from the gay issue, it's about things which are very current at the minute - the conversation between north and south and between London and rural England. It seemed the right time to do a play that's about distances between us which are cultural and economic and social.

"And of course to present the same play in both London and now in Yorkshire seemed perfect."

Batt appeared as a cross-dressing footballer in the most recent series of W1A

The play is a rare example in modern British theatre of a powerful and deeply emotional love story. But isn't that one of the things audiences crave most?

Gill says he was writing "a romantic play but also a grown-up play".

"For George and John there was never a prospect of things ending happily - but I don't think happy endings really exist in life anyway. Of course I could have invented one but it wouldn't have been credible - unfortunately I'm not Dickens."

Gill thinks we're living through what he calls queasy times politically. But he's pleased that audiences seem now to respond to his gay love story more freely than 17 years ago.

"There's a definite difference: the original audience in 2001 was receptive but you could also tell it was troubled by the subject. Now all that has gone - audiences accept the relationship between George and John without question.

"People don't now seem to ask themselves if they're supposed to approve or disapprove. That's over now, we hope. And I do take that as a move forward."

The York Realist is at the Crucible Theatre, Sheffield from 27 March.