Review: Kettle's Yard in Cambridge ★★★½

- Published

If I had Elon Musk-type money, I would hire a top-notch art gallery curator to clean my house.

I would happily be the assistant, undertaking the most menial tasks while the duster-wielding curator concentrated on doing what curators do better than anyone else in the world, which is to arrange things really nicely.

Making the shabby chic, transforming a total mess into a harmonious, tonal, soul-calming, eye-pleasing composition is the curator's art. It is a form of alchemy that is genuinely a wonder to behold.

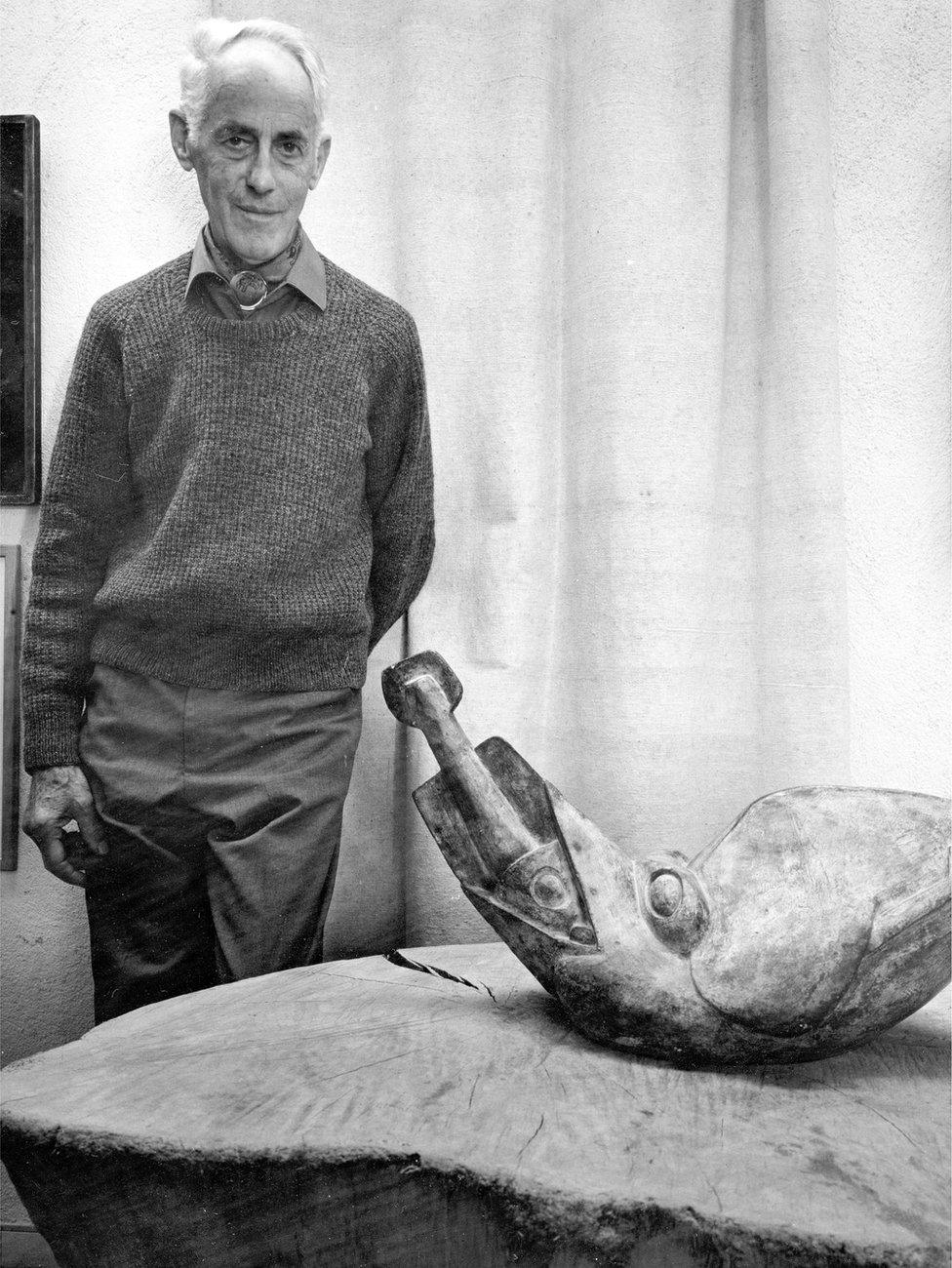

You will know this if you've ever been to Kettle's Yard in Cambridge, the former home of one-time Tate Gallery curator Jim Ede and his wife Helen.

Jim Ede bought Kettle's Yard in the 1950s

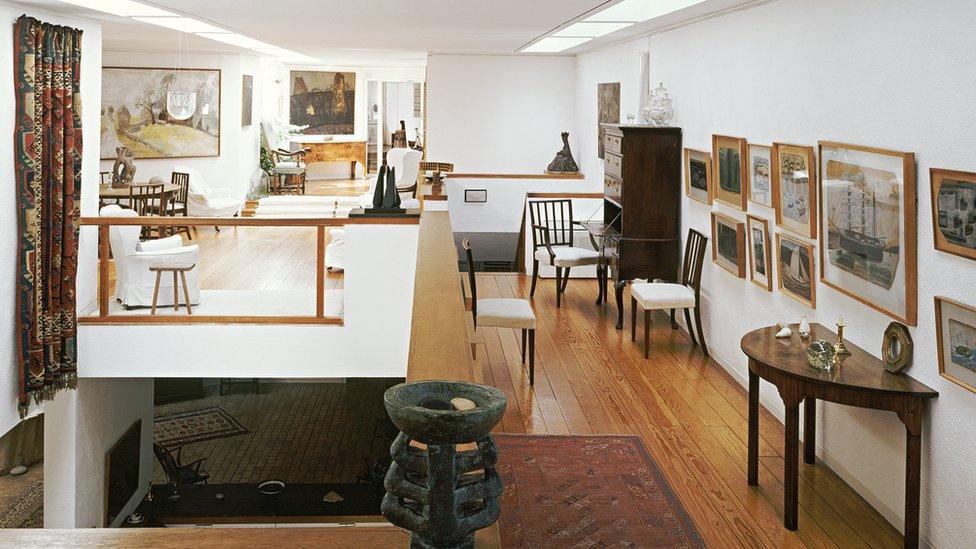

From the leather roundel you pull to gain entry, to the Brancusi sculpture of a reclining head placed casually on the lid of a grand piano, every inch, every sightline, has been meticulously considered and intricately planned to deliver the ultimate aesthetic experience.

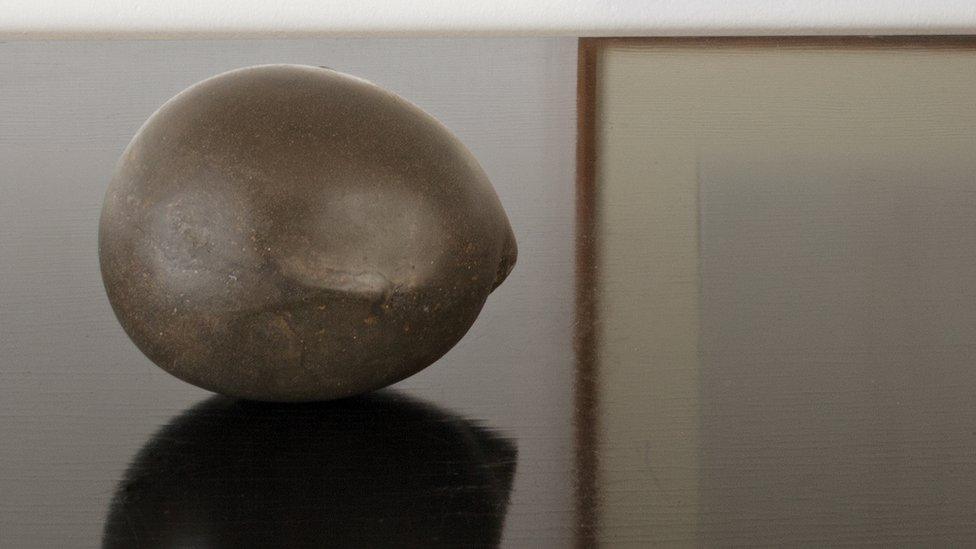

Prometheus by Brancusi

Jim gave as much curatorial care and attention to arranging the pebbles he picked up on the beach as he did to his splendid collection of modernist art.

Everything mattered.

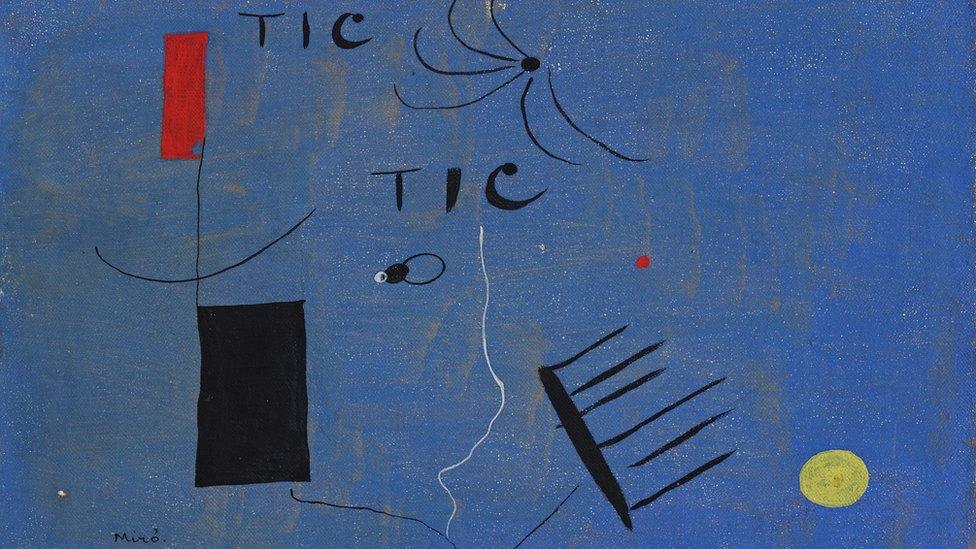

For instance, in the front room there is a small Joan Miro surrealist painting hanging above a spiralled, totemic wooden cider press, to the side of which is a large pewter plate. On that plate is a single fresh lemon, placed on the outer rim and positioned at precisely nine o'clock.

Why? Because the fruit's bright yellowness accentuates the solemn greyness of the pewter while also echoing the small lemon shape in Miro's painting, which is at about three o'clock in the picture.

As far as the Edes were concerned, the devil wasn't in the detail, beauty was.

Tic Tic (1927) by Joan Miro

There are hundreds of similar curatorial touches to enjoy as you make your way around the house, which was once four small slum cottages before Jim and Helen bought and renovated them into one dwelling in 1957.

Their attention to detail didn't stop at the objects, or even the display thereof; it encompassed the entire experience, most particularly how light affects everything we see and sense.

Their idea was to keep "open house" every afternoon of the academic term for students and anyone else so inclined to visit "a living place where works of art could be enjoyed, inherent to the domestic". It was "in no way meant to be an art gallery or museum".

That was in the late 50s. In 1966, while still living at Kettle's Yard, the Edes gave the house, its contents, and the majority of their art collection to the University of Cambridge. Before long, the initial trickle of one or two interested students a day had turned into mass of tens, then hundreds, and eventually many thousands of visitors a year.

A sympathetic, Le Corbusier-inspired extension was built in 1970 by Sir Leslie Martin and David Owers to accommodate the ever-expanding number of artworks, artefacts and art lovers.

The Edes left in 1973 to live in peace and quiet in Scotland.

Since then, Kettle's Yard has continued to develop in a slightly haphazard fashion, until the decision was made a few years ago to employ Jamie Fobert (the go-to art world architect for sensitive design projects) to bring some order to the site by creating a new suite of galleries, education spaces, and offices.

On Saturday, they open to the public, who will be the first beneficiaries of a proper reception area, cafe and shop.

Kettle’s Yard is reopening after an £11.3 million redevelopment by architect Jamie Fobert

The new galleries are fine, and they have some nice touches, and I'm sure lots of modern art will look good in them.

But I have to admit to being just a little bit disappointed by the rather hackneyed combination of concrete floor, smooth white wall and double-height ceiling.

Such spaces are two-a-penny nowadays.

They are like Prada stores and Range Rovers, classy but now irritatingly ubiquitous; chilly corporate spaces beloved by big-shot art dealers and major modern art museums. They struck me to be at odds with the Edes' founding principle of seeing art in a domestic setting.

It's probably my fault for being a hopeless romantic, and I'm sure I'll enjoy many exhibitions held in them over the coming years (the inaugural show, Actions. The Image of the World Can Be Different feels like a limbering up exercise), but I can't help wondering if they are an opportunity missed.

The Edes' taste was for mottled walls, light timber, and local brick. Domestic materials. I didn't detect an obvious love for polished concrete or austere environments.

But this is only a small gripe about one of the great oases of culture in an increasingly vulgar world. The updating of Kettle's Yard was necessary and it has been done lovingly and thoughtfully by a team who care passionately about it - and us.

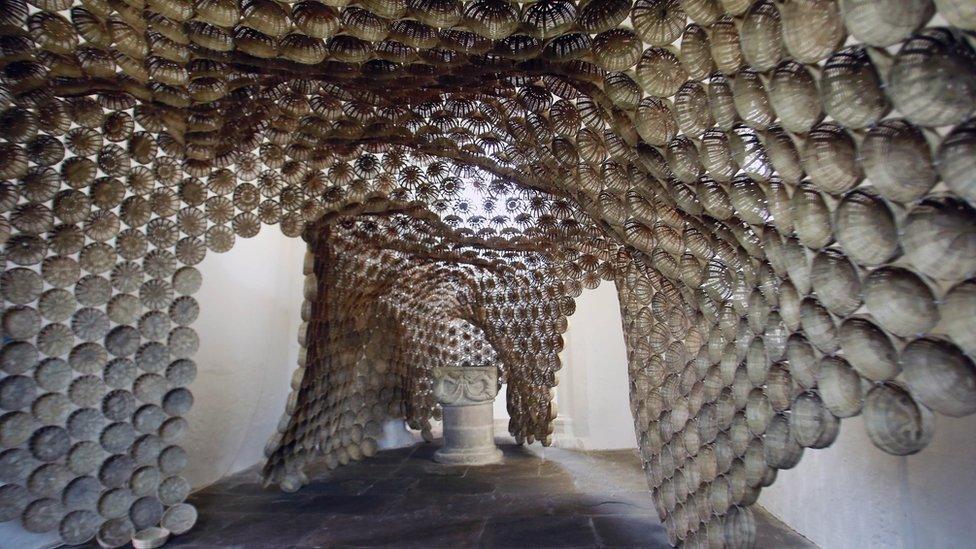

Rana Begum's installation of bamboo baskets, No. 764 Baskets at St Peter's Church, Cambridge

When you go, and I urge you to do so, make the time to pop into the small church by the house which has a sculptural installation made from baskets by the artist Rana Begum. It is quiet and sensitive with an inherent warmth that completely captures the spirit of Kettle's Yard.