The autistic musician who 'makes music with his mind'

- Published

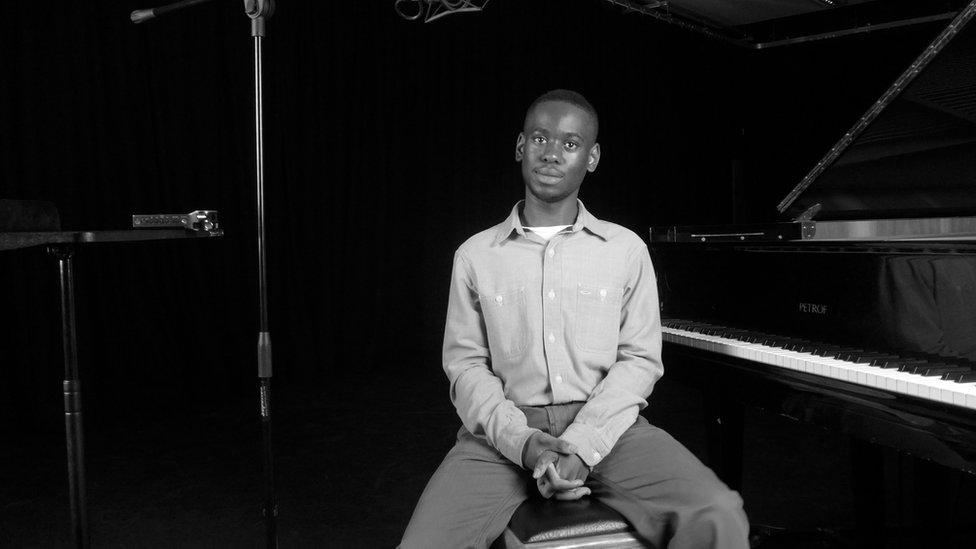

Meet Michael Fuller, the autistic teen who 'downloads music into his head'

There is nothing conventional about 17-year-old Michael Fuller's relationship with music.

As someone with high-functioning autism who sees the world through sound, creating melodies from the bustle of the high street or trains on the tracks feels more natural than any social interaction.

This hardwired connection to sound has been with him for as long as he can remember.

By the age of 11, Michael could play Mozart by ear, having taught himself to play the piano through a mobile phone app. The app highlighted notes on a keyboard as classical music played.

He describes his unusual musical talent as "downloading" music into his head.

His mother, Nadine, remembers that as a child Michael would "suddenly pop up and say: 'I've got a symphony'".

Michael says he allows the music "to takeover" when performing

Michael took to the piano and found he could quickly perform complex pieces from memory.

"I liked what I was hearing, sought more music and began studying through Google and YouTube," he remembers.

"It was very organic. I would listen in great depth and the music would be implanted in my mind.

"I could then just play it on the piano - all without being taught."

Growing up in a family that listened to reggae over classical music, Michael feels "very much aware" of how different his approach is to music - symbolised by the way he taught himself piano as a child.

This, his mother says, came as a "surprise to the family and myself - I'd never listened to classical music in my life".

It was not long after learning to play the piano that Michael started composing his own works.

Describing this process as "making music with my mind", Michael says composing classical symphonies "helps me to express myself through music - it makes me calm".

Michael performing his own composition at the piano

"Any sort of sound appeals and fascinates me - I just cling on to it and I start to compose music," he explains.

He found it helped him express his emotions, which like many autistic people he struggles to put into words.

Michael says he lets the music come to him in a flash of inspiration he calls "the moment."

"I allow the music to take over - there's no planning, it just happens," he says.

The sense of surrendering to music is not unusual in musical circles, but Michael says the extent to which he does so is what sets him apart - the music comes from within him and has a life of its own.

Finding his voice

As a child, Michael would always hum, but the full extent of Michael's talent was only discovered by chance - when his music teacher, Emma Taylor, heard him singing to himself in the school corridor.

Ms Taylor ran out into the hallway and offered to help Michael nurture his talent and she continues to teach him singing.

Now studying a BTEC diploma in performing arts at Richmond College in Twickenham, Michael's passion for music is reaching new heights.

He credits the writing module of the course with helping him try to tackle his difficulties expressing emotions.

Allow YouTube content?

This article contains content provided by Google YouTube. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read Google’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

To begin with, Michael combined random words from multiple foreign languages - a technique known as nonsense music - to mask his struggle with lyrics.

But now Michael has written a number of pieces featuring his own lyrics.

Nadine has noticed a difference, saying he is now "singing what's inside" of him.

Autism and special abilities

It is not known how or why people with autism sometimes develop special skills.

However, explanations may include:

Interacting with others can be a challenge for people with autism, which may explain why their special interests are often solitary

People with autism can find it difficult to cope with changes in routine, which is why they may value the predictability of a particular activity

People with autism often demonstrate both a great attention to detail and an ability to remain focused on a task for long periods of time, can lead to them becoming highly skilled in their chosen field.

Source: Dimensions, external

Michael wants to nurture his song writing to achieve his ambition of becoming a modern mainstream classical artist.

He wants to control the creative process, unlike typical modern-day composers, who he says "write blobs on a page, hand it over to the musicians - then say bye-bye and stay in the background and get no recognition".

Instead, Michael is determined to take centre stage.

"I want to go mainstream in my own right, and I don't just mean singing in opera houses," he says.

"I can write, compose and sing. People might be surprised but I am ambitious."

Part of the reason for this drive lies beyond music. As a black person with Jamaican roots, Michael says a lot of people are "surprised and astonished" to see him performing classical music.

"It makes me feel sad - I don't like how society says no to people due to the colour of their skin, their roots, or their family class status.

"That prevents people who have talent to do something."

Michael with his mother, Nadine, who says she is "proud" of her son

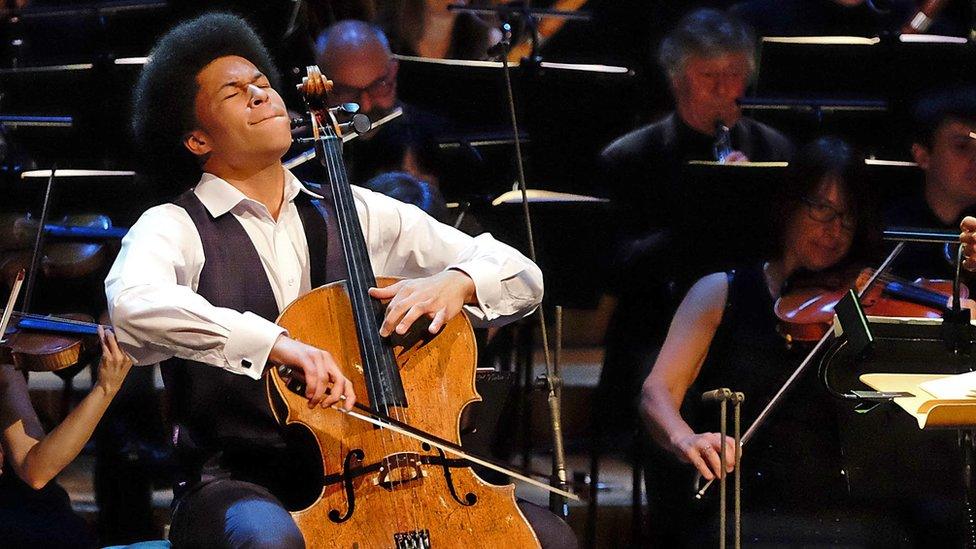

Looking to the future, he takes heart from the success of Sheku Kanneh-Mason - the first black musician to win the BBC Young Musician of the Year award in 2016.

The cellist has since scored the biggest-selling British debut record of the year to date with his classical album, fittingly titled "Inspiration".

"I believe he is an idol - I support him," says Michael.

Michael's biggest supporter however, remains his mother.

"There was a lot of negativity when he was growing [up] with autism," she says.

"A bit of bullying and teachers didn't understand him.

"Seeing him doing so well in college now… when I hear him sing, it's just greatness - I feel proud of him."

Video produced by Hannah Gelbart

Related topics

- Published20 October 2016

- Published26 January 2018