Review: Picasso at Tate Modern ★★★★★

- Published

One of the best things about Tate Modern's Picasso exhibition is it contains some terrible art. I mean real howlers. Paintings in which we see the modern master fluffing his lines and losing his form.

It's such a relief.

Not because we learn he is fallible like the rest of us - we're not idiots, we know artists aren't gods - but it shows the exhibition's curators had the confidence and integrity to tell the whole story of Pablo Picasso in 1932 - his so-called annus mirabilis - and not palm us off with a superficial Now That's What I Call Picasso '32: Greatest Hits compilation.

I'm not saying the show is packed with turkeys, far from it. But there are enough duds for you to be able to appreciate those moments when the prolific Spaniard went into masterpiece mode, as he did with Nude in a Black Armchair.

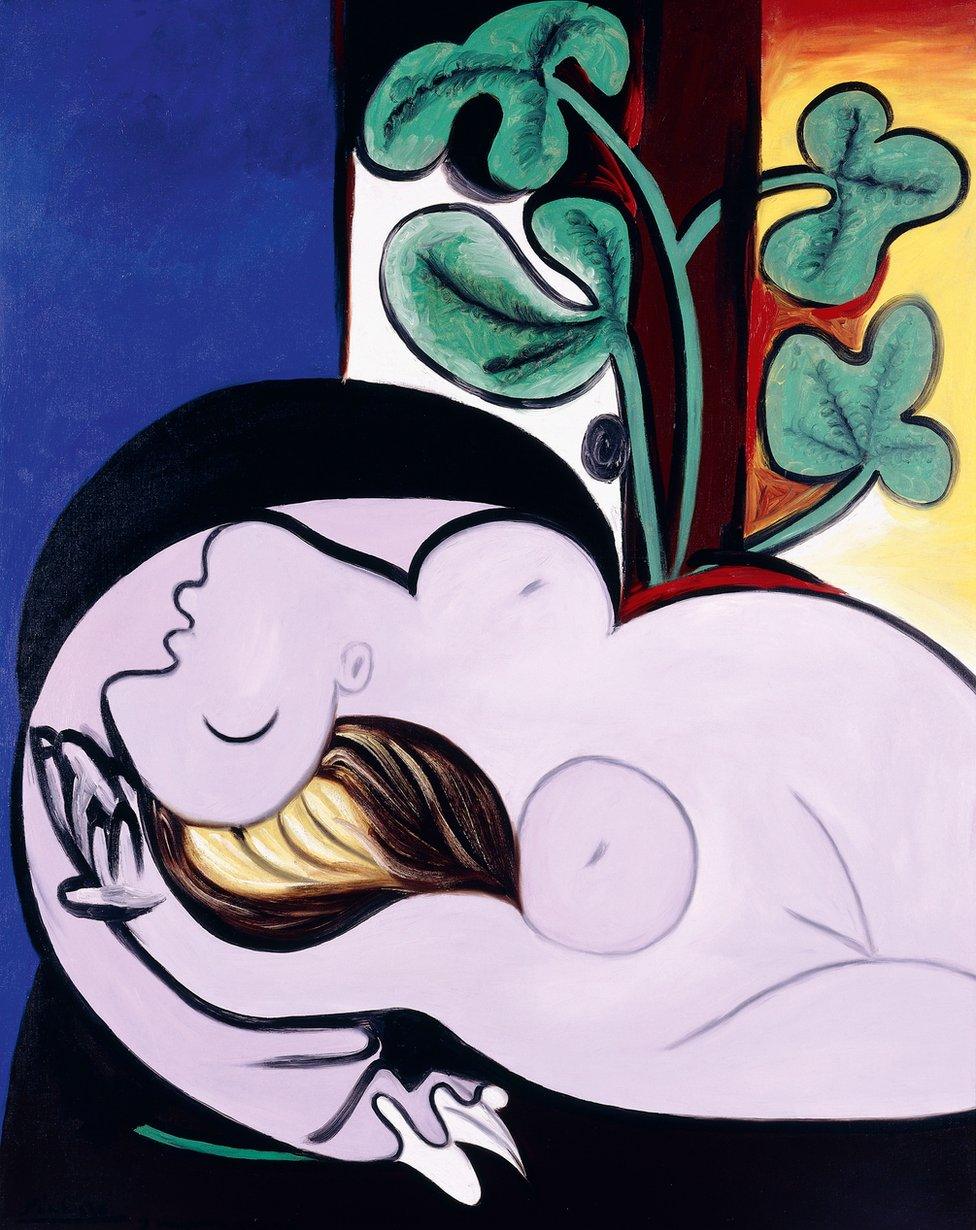

Nu au fauteuil noir (Nude in a Black Armchair)

This is a painting of such exquisite beauty, balance and sensuality you have no option but to stop and stare. And the more you look, the more you see.

At first glance, there is a voluptuous reclining female nude on a black chair, lit by a fiery sun, visible though a window that is partially obscured by the green leaves of an indoor plant.

You note the obvious influences in both composition and style. There's a hint of Titian's Venus, of Manet's Olympia, and Matisse's Odalisque with Magnolias.

And then there is the evidence of Picasso's own artistic journey: a slab of blue from his early days, the disjointed body parts echoing his Cubist period, the sinuous lines of his post-war modernist-primitivism, and the otherworldly dreaminess of his more recent interest in surrealism.

But (at the risk of sounding like a total phoney), it is its soul that mesmerises. It is so poetic, and erotic, and sonorous. This is a painting of love spelt out in the graceful fluidity of the artist's line and harmonic balance of his colours.

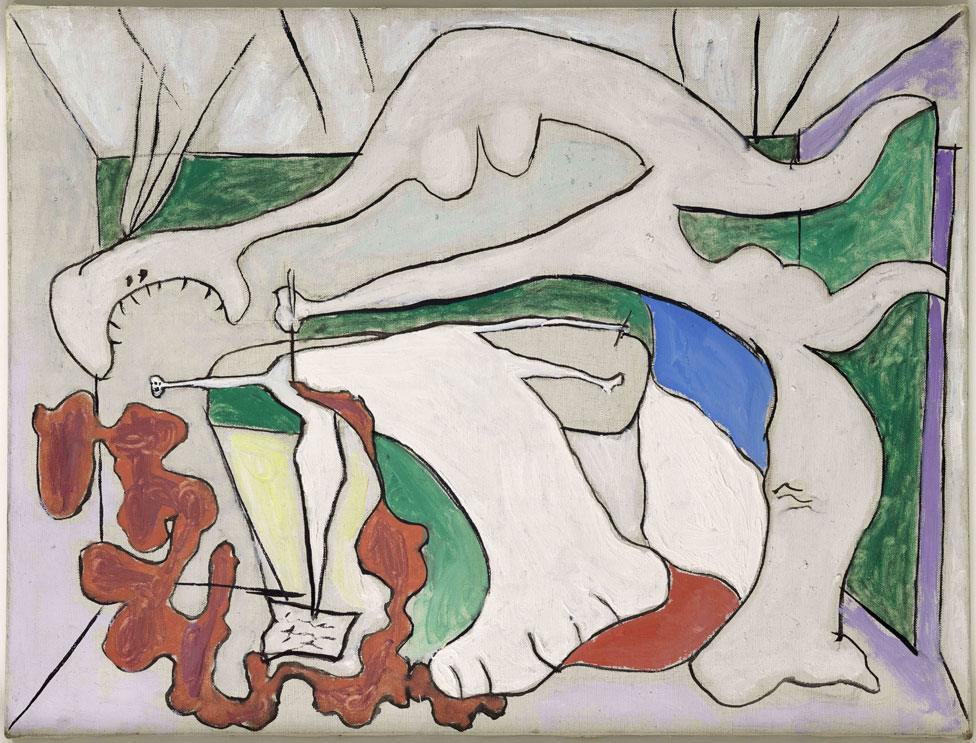

Nu sur la plage (Woman on the Beach)

The subject of his adoration is a 22-year-old Parisian called Marie-Therese Walter, who had been his lover for the past five years. They met by chance in 1927 at the Galeries Lafayette department store, where he told her she had "an interesting face" and that he'd like to do a portrait of her.

He introduced himself as Picasso. She had no idea who he was, but the chat-up line worked all the same.

Within weeks they were lovers, although the then 45-year-old artist was already married to Olga, a Russian ballerina who had danced with Sergei Diagilev's famous Ballets Russes.

Their marriage wasn't going terribly well.

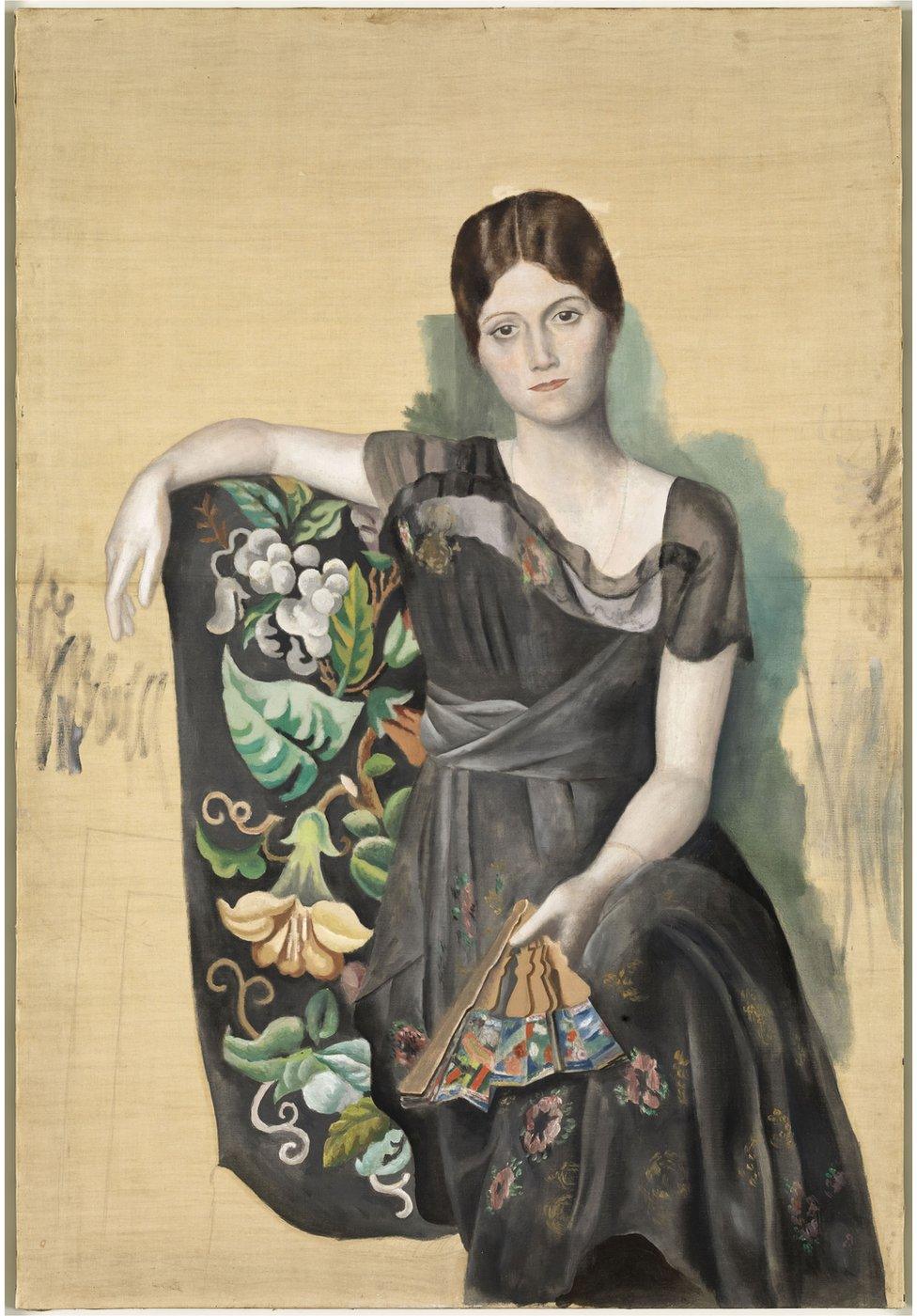

Portrait of Olga in an Armchair, 1918

Olga was increasingly anxious about the relationship, which was not unreasonable as her husband was a serial philanderer. She yearned to settle down to a bourgeois life of respectability with smart friends, smart clothes, and smart homes.

Picasso did not. Well, not quite as much, anyway. He wanted to rekindle the bohemian excitement of his youth, to recharge his creative batteries, and to go again.

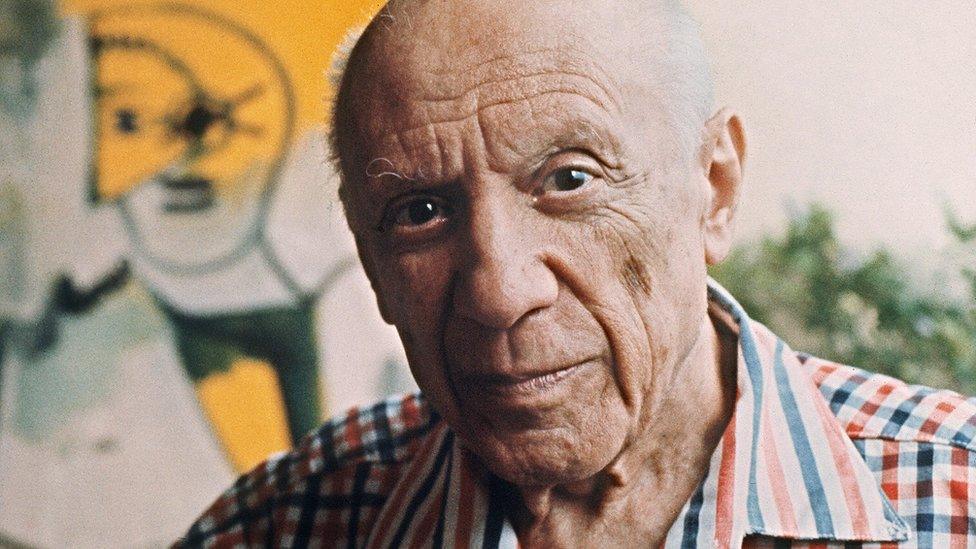

This is the middle-aged man we meet in the exhibition. An artist at the crossroads of his career with a major retrospective of his work planned for the summer (restaged in part in this Tate show), which he hopes will, once and for all, establish him as the greatest living artist in the world.

For this to happen, the mid-life crisis he is experiencing urgently needs to be resolved.

Marie-Therese is his way out. She will be his inspiration, his muse, and his weapon against Henri Matisse, his great rival for the world art crown.

But before we can get to her, he needs to deal with Olga, to whom we are introduced at the beginning of the exhibition, in an angry, jagged painting called Woman with Dagger.

La Femme au stylet (Woman with Dagger)

It is Picasso's re-imaging of Jacques-Louis David's iconic painting, The Death of Marat, external (1793).

The themes of betrayal, revenge, and a murdered competitor unite the two images, but while David's has an air of resignation, Picasso's is full of rage.

If this is indeed a painting of Olga attacking a rival - or even if it's not - it vividly demonstrates what a poisoned chalice it was to be Picasso's lover.

At first there is the charm and generosity when you are immortalised on canvas or in stone by the gifted artist. But when your time was up, his unkindness and thoughtlessness could be so devastating and destructive as to drive you to the point of insanity.

So, while you walk around this exhibition and see painting after painting that explores his passion for Marie-Therese, together with their little in-jokes and furtive allusions, there is something ominous about these images of the young, athletic woman being depicted and manipulated.

Take a look at The Dream for example; a technically excellent painting that makes you feel uneasy. We see Marie-Therese asleep in a red armchair, her head resting on one shoulder, with her left breast exposed in the classical manner.

Le Reve (The Dream)

Her hands rest suggestively on her lap, while half her face has been turned into a phallus.

The explicit suggestion being she has sex on her mind. But does she? Isn't she asleep? The artist couldn't possibly know what she was dreaming, could he? Isn't this more likely the imposition of Picasso's unconscious (or conscious) thoughts projected onto his young lover?

The exhibition asks you that question time and time again. What's going on here? Which is probably exactly what Picasso was asking himself, as he pushed the boundaries and possibilities of his art further and further.

The result of this intense period of painting and sculpting (the bulbous, phallic busts he made of Marie-Therese's head have a disturbing Elephant Man-like quality), is a year's worth of work that is very impressive on many fronts.

What painter today is challenging the medium in the same way Picasso did nearly 80 years ago? Maybe he took it as far as it would go?

He certainly took a lot of risks, not all of which paid off, and that is the joy of this show - you actually get to see him struggling to find a new form of visual expression.

Picasso might have been a flawed man, but see this show and be in no doubt, he was a truly great artist.

- Published21 September 2017