Review: America's Cool Modernism at the Ashmolean ★★★★☆

- Published

A quick glance at the form-book of blockbuster exhibitions will tell you we like paintings with people in them. Rembrandt's portraits for example, or Da Vinci's Mona Lisa, or - currently - Picasso's depictions of his young lover at Tate Modern. They all get us going.

True, we don't mind the odd landscape, but usually only when it reminds us of Nature's great power and beauty and our place in it. And yes, we'll happily tip up to a show of abstract art as long as it's packed with Matisse or Rothko-like emotion.

Mostly, though, we like to look at ourselves.

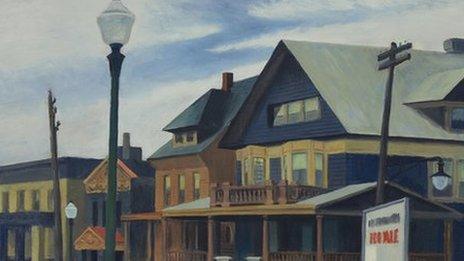

Which makes the Ashmolean Museum's decision to mount a major exhibition of inter-war American paintings - on the basis that they are aggressively unpopulated and as emotionally charged as a paving slab - appear quite bold.

It's called America's Cool Modernism, but that's a misnomer.

People-free zone: Illinois Central by George Josimovich

The paintings you'll see by artists, many of whom you've probably not heard of - Ralston Crawford, Louis Lozowick, Samuel Margolies - are not cool.

They're chillier than the Beast from the East.

We see isolated grain silos and deserted cityscapes, uninhabited interiors and bleak factories.

People? There are none. Humanity's imprint is there but we are missing.

A surreal, macabre atmosphere hangs over this exhibition like the Great Depression. Think Giorgio de Chirico without the warmth and the wit.

Fun, it is not. Which is not to say it isn't good. It is, on the whole.

Edward Steichen's The Sunflower - nice cop?

The first room is thoroughly enjoyable. It plays a sort of nice cop before you meet the miserable cop in the subsequent rooms.

The first painting you see is of a joyful, colourful, Leger-inspired still-life by Edward Steichen called Le Tournesol (The Sunflower - 1920). Tonally, it is a world away from most of the other works in the show, but it does represent some of the main themes.

The first was the breakaway the American painters wanted to make from the largely Paris-based European avant-garde after the First World War. They were trying to create a distinct visual language to reflect America's coming of age as a super-power, in the same way the Constructivists had done for the newly communist Russia.

It wasn't easy. We see painting after painting owing everything to those all-pervasive early 20th Century European …isms: Cubism, Futurism, Fauvism and Orphism.

Sound by EE Cummings (the poet)

There's one by EE Cummings (yes, that one), which is his attempt to take on Delaunay and Kupka at their own game. Suffice it to say, becoming a poet was the right career choice for him.

But there are others where you start to see an independent voice break out.

A small abstract painting from 1919 by Georgia O'Keeffe, called Black Abstraction, combines European concerns for perspective with a uniquely American sensitivity to a high-rise urban life.

Abstraction by Georgia O'Keeffe: An independent voice

Next to it is a still-life by Helen Torr, called Purple and Green Leaves (1927). It's not the best painting in the world but she was clearly a painter who knew how to make an impactful image. I liked its allusion to a stained-glass window.

She was one of several artists in the show whose work I didn't know at all - I was delighted to see it for the first time. Particularly Houses on a Barge (1929), a predominately dark brown painting made in an abstracted naive style.

It is terrific: dark but wry, a Noah's Ark of homes, which foreshadows Louise Bourgeois's surrealist 1940-50s Manhattan images.

The main gallery is packed with pictures of urban emptiness, many of which have been lent by the Metropolitan Museum in New York, the most famous being the colourful, Picasso-inspired I Saw the Figure 5 in Gold (1928) by Charles Demuth.

I Saw the Figure 5 in Gold by Charles Demuth appears to be inspired by Picasso

What a fine artist he was, as you will see from this well-known work that makes visible William Carlos Williams' poem The Great Figure, external. There are two other paintings by him nearby, both of which are worth spending some time looking at.

The same does not apply to all the work in the show. An odd piece called Painting No 50 (1914-15) by Marsden Hartley in which he references a tepee, is one I wouldn't have included.

But for every miss there are plenty of hits.

Two small, simple pictures by Jacob Lawrence from his early 1940s Migration Series gives an all-too-brief African American perspective on this extraordinary period of American History.

Their titles tell you all you need to know: The Migration Series, panel No 25 ("They left their homes. Soon some communities were left almost empty") and The Migration Series, panel No 31 ("The migrants found improved housing when they arrived north").

Migration 31 is a simple picture by Jacob Lawrence

There are pictures in this show you will remember forever. One of which is Charles Sheeler's vertiginous Americana (1931) in which you see a deserted sitting room with everything left just-so. It's eerie and disorientating, with its extreme perspective and clashing rug patterns combining to make a visual assault on your senses.

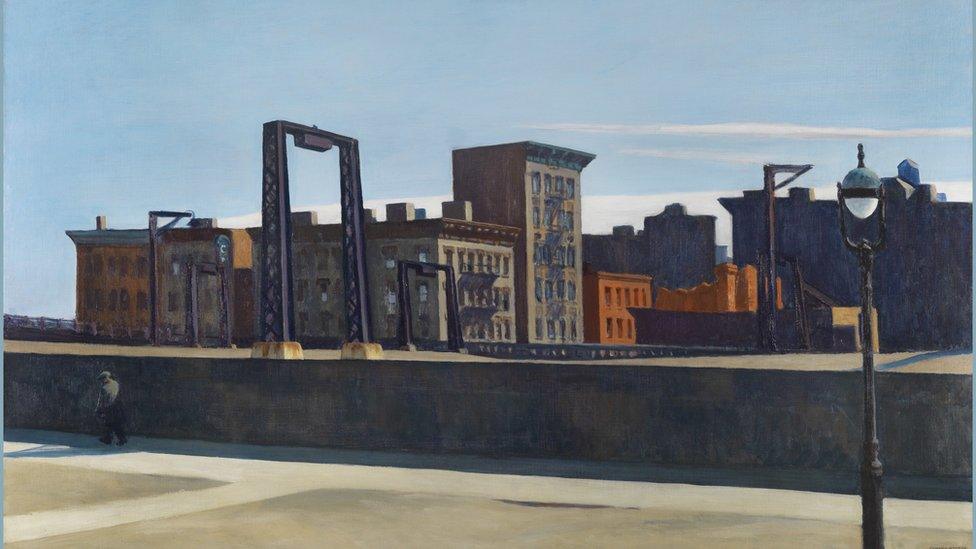

By the time you arrive at the three paintings by Edward Hopper, with which the show ends, your mind has been re-set, making these works by one of the most famous American artists of the period jar a little.

They feel overly fussy, more moody and emotional than what has gone before - added to which two of them contain human beings!

And that, if anything, gives you a sense of this impressive, intelligent show. After all, it really takes something to make an Edward Hopper painting feel overly populated.

Manhattan Bridge Loop by Edward Hopper

- Published6 December 2013

- Published13 June 2012