Will Gompertz reviews David Mamet's Chicago ★★★★☆

- Published

If you're thinking of going on a creative writing course, don't.

Save your money and read David Mamet's new thriller Chicago instead. It's a whole lot cheaper and you'll learn all you need to fulfil your literary dream.

Mamet can write. We know that.

He's got a Pulitzer Prize to prove it.

Plays and movies are where he has made his literary name. American Buffalo, Glengarry Glen Ross, The Untouchables, The Postman Always Rings Twice: it's not a bad CV.

Dialogue is his thing.

He's got a reputation for it.

So much so, it has its own name, Mametspeak.

This novel is packed with it: dense passages of jargon-laden conversations between earthy, cynical protagonists who finish off each other's sentences, if the sentences get finished at all.

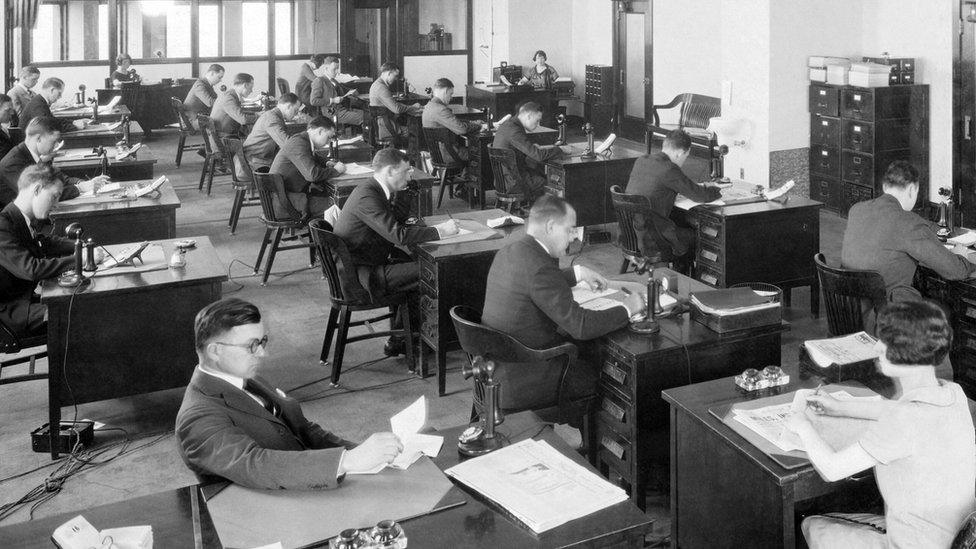

The bulk of the chat in this instance is between two old-school, hard-boiled, inky journalists called Mike Hodge and Clement Parlow who work in Coffin Corner at the Chicago Tribune, so called because "it was the place stories went to die".

Chicago Tribune newsroom, circa 1923

"Is non-coterminous a word?" Parlow said.

"It is if you want it to be," Mike said. "Read Walt Whitman."

"I can't. It makes me sick with envy," Parlow said.

And so it goes.

We're in Prohibition-era 1920s Chicago where the rat-a-tat speed of their conversations matches the sound of guns being fired around the mean streets and back alleys of the corrupt, violent, crime-ridden city on which they report.

Contraband beer being spilled into the streets from barrels during the Prohibition era

It is a story soaked in illicit whisky and the warm blood of dead mobsters. The Italians run one side of town, the Irish the other. Between the two are the Jews. Everyone is on the make; the only thing going straight are the bullets.

The story takes a while to get going. The first third of the book, the set-up, is about getting the atmospherics right; dragging us back a century, filling in the characters' back-stories, hearing them bicker about journalism.

"What do you think they're paying us for?" Crouch [the news editor] had said.

"Man bites dog," Mike had said.

"Bullshit." Crouch said. "Man bites dog is too interesting to be news."

"Then what is news?" Mike said.

"News," Crouch said, "is that which makes its consumer self-important, angry, or sufficiently whatever the hell to turn to page twelve, and, turning, encounter the ad for the carpet sale."

Most of our time is spent hanging out in speakeasies and brothels, where new characters emerge and plot lines are planted with the subtly of a brown paper bag changing hands on a park bench.

By the time the story finally kicks off, Mike has fallen in love, two local "faces" have been murdered, and a couple of goons wearing unusual overcoats are lurking ominously in the background like an old score about to be settled.

At this point the novel morphs from being a thoroughly enjoyable period piece into a slug of genre writing that belongs to the era in which it is set. We're talking Pulp Fiction.

"They said that knowledge is power."

"Power is power," Ruth said. "People say differently don't understand power. Or knowledge. Knowledge is what gets you killed."

The pace changes. There's less chat and more action.

Al Capone makes a cameo.

American mobster Al Capone, makes a cameo appearance in the novel, Chicago

Things turn nasty.

And life gets complicated, as Mike discovers the people on whom he is relying are more unreliable than backstreet gin.

It is not a perfect novel.

There are some bum notes to go alongside the groovy chords Mamet creates with his rhythmic dialogue.

David Mamet

He undermines his character Peekaboo, the all-seeing African American madam at the Ace of Space whorehouse, by making her reveal far more information than she ever would to Mike - without getting anything in return.

And there are moments, not many but some, where he overwrites in a way that the masters of the American crime novel like Raymond Chandler or Elmore Leonard, never would.

That though is being picky.

If you like your language dense, if you're interested to see it being toyed with by a maestro, and if you fancy a blokey whodunnit to while away the hours until some half-decent weather arrives, then you could do a lot worse than hang out in David Mamet's Chicago.