Will Gompertz reviews Monet and Architecture at London's National Gallery ★★★★☆

- Published

This is what you will hear at the National Gallery's blockbuster Monet and Architecture exhibition, which opened to the public this week:

"Excuse me."

"Excuse me."

"Excuse me."

"Can I just…"

"Sorry."

"Ouch!"

It is the sound art-lovers make when gathered en masse in a confined space full of eye-popping pictures by one of the finest painters to have ever picked up a brush.

Call it the Monet Mumble: the polite but insistent whispers uttered by well-dressed ladies and gentleman making their way around packed galleries.

Much has been made about the amount of money the National Gallery is charging punters for the privilege of seeing its Monet show while having their toes trodden on (I was on the receiving end twice, and the apologetic perpetrator once).

If you have the audacity to go for the 'Admission Only' option and ignore the explicit and assumed 'suggested' £2 donation, tickets purchased online for those over 11 years old cost £18 during the week and £20 at the weekend (they are £2 more if bought in the gallery). That works out at around 25p a painting (there are 78 in the show).

Value for money, you could argue.

Particularly when you take into account the ever-increasing costs incurred by museums when putting on such ambitious, 'once-in-a-lifetime' exhibitions.

That said, there must be scope to be a bit more innovative and flexible on pricing when planning a sure-fire box office smash, which will be too pricey for too many (e.g. students, families with teenagers, the currently unemployed, low paid workers).

The gallery has clearly thought about the visitor experience.

Houses of Parliament, Sunset (Le Parlement, coucher de soleil), 1900-1

For the first time, there are no wall texts beside the paintings, just a number, which you then refer to in the small booklet that comes with your ticket.

The upshot is rooms full of earnest, bespectacled faces peering down at this bijou publication like race-goers studying the formbook at the Grand National.

From time-to-time we look up and cross-reference text with picture, before an "excuse me" and move on.

It is a better system than having mini essays by pictures, which causes large huddles of people to gather to the side of paintings like giant barnacles. But I'd prefer a half-way house that had a sparse wall caption stating the artwork's date and title, and a booklet for the details.

As for the show itself, well…

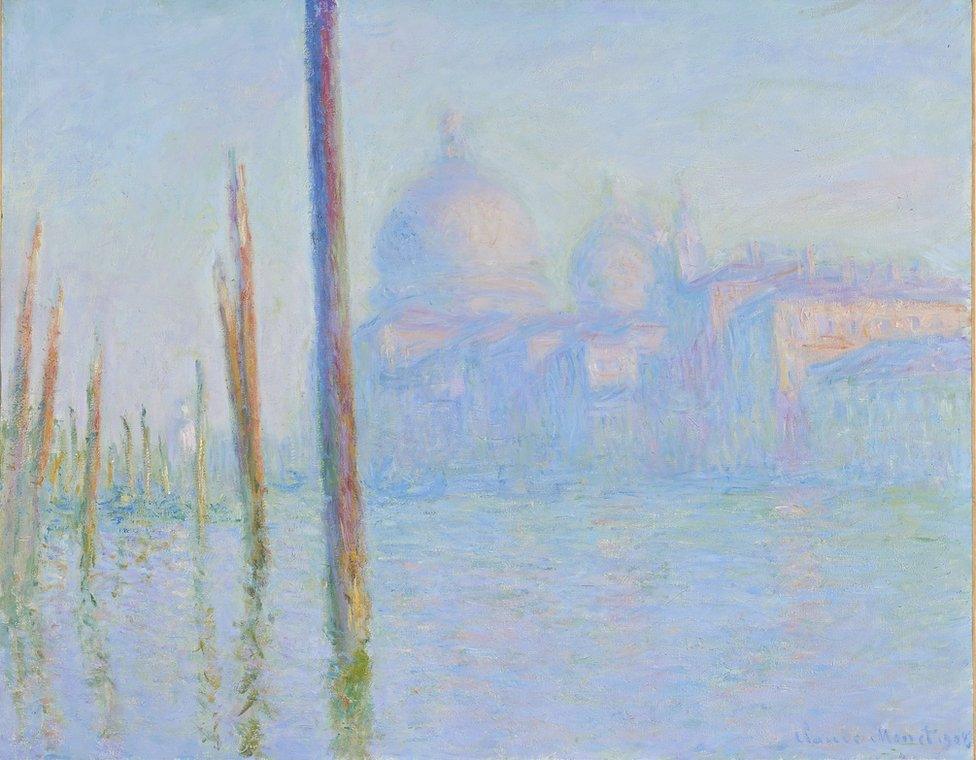

The Grand Canal, Venice, 1908

It is very good.

Although the title is misleading. Monet had no formal interest in architecture.

Canaletto painted architecture.

You could argue Ed Ruscha paints architecture.

But not Monet.

Never Monet.

His concern was with the immaterial.

Monet only ever really painted two things, both of which are as ephemeral as a snap-chat. His subjects were light and air.

The Water-Lily Pond (Le Bassin aux nympheas), Giverny, 1899

"Other painters paint a bridge, a house, a boat" he once said,

"I want to paint the air that surrounds the bridge, the house, the boat - the beauty of light in which they exist."

Yes, there are buildings in every one of the paintings on show at the National Gallery.

Sometimes - as is the case with his spectacular depictions of the medieval façade of Rouen Cathedral - the same building many times over.

But Monet is not exploring its architectural characteristics.

For him it is a superficial motif: a compelling surface on which light falls to create an all-enveloping "atmosphere".

Rouen Cathedral: The Portal (Morning Effect), Normandy, 1894

He painted the same façade from the same spot dozens of times in the early 1890s.

Not to show the intricate details of every nook and cranny, but to capture how the changing light and weather conditions physically altered the 'impression' of what he saw.

"Colour, a single colour, lasts a second, sometimes three or four minutes at most. What can one do, can one paint, in three or four minutes?" He said to the dealer René Gimpel.

Monet was the ultimate Impressionist; an on-the-spot improviser reacting to Nature's every move, however small.

Buildings were useful to him in terms of providing a compositional structure, a consistent reference point, and a means of evoking mood. As you can see in Snow Effect at Giverny (1893), which is an utterly wonderful, beautifully rendered psychological depiction of a rural landscape covered in snow.

Snow Effect at Giverny (Effet de neige a Giverny), 1893

It is not a literal account of what was before the artist, nor is it of what he felt about what he saw (that was Van Gogh's shtick); it is a sensational interpretation of the experience of looking at that particular moment: a manifestation in oil paint on canvas of Monet's senses reporting back live from the scene.

His best paintings, of which there are several examples in this show, have an almost electric sense of immediacy.

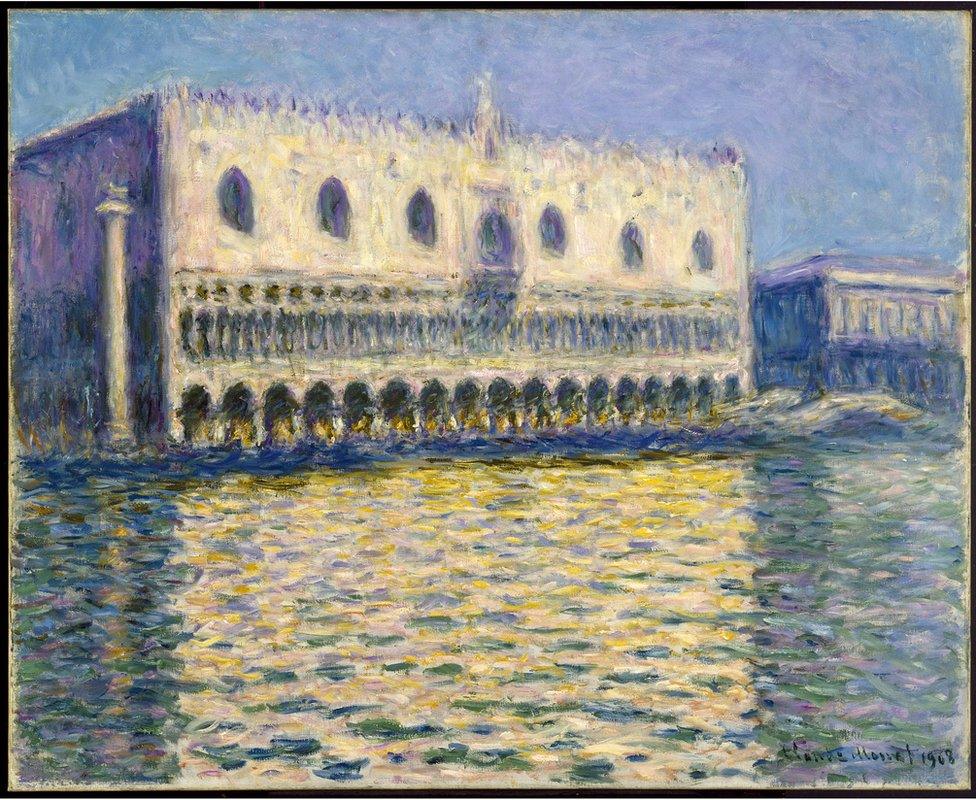

The Doge's Palace (Le Palais ducal), Venice, 1908

Whether it is Normandy, the Netherlands, the Mediterranean coast, or Venice - he takes you there in an instant.

If you can afford the ticket price and don't mind crowded spaces (there's still plenty of room to see the paintings and no sense of being rushed through), I would thoroughly recommend you see this show.

You will meet a Monet you know and one that you don't.

You'll see how he progressed from Courbet-type realism in his early twenties into a dare-devil picture-maker who changed the way we look at our world.

Nobody thought about art in the way he did:

"When you go out to paint, try to forget what objects you have before you, a tree, a house, a field or whatever. Merely think, here is a little square of blue, here an oblong of pink, here a streak of yellow, and paint it just as it looks to you, the exact colour and shape, until it gives your own naïve impression of the scene before you."

The Saint-Lazare Railway Station (La Gare Saint-Lazare), Paris 1877