When Burnley was Britain's theatre capital

- Published

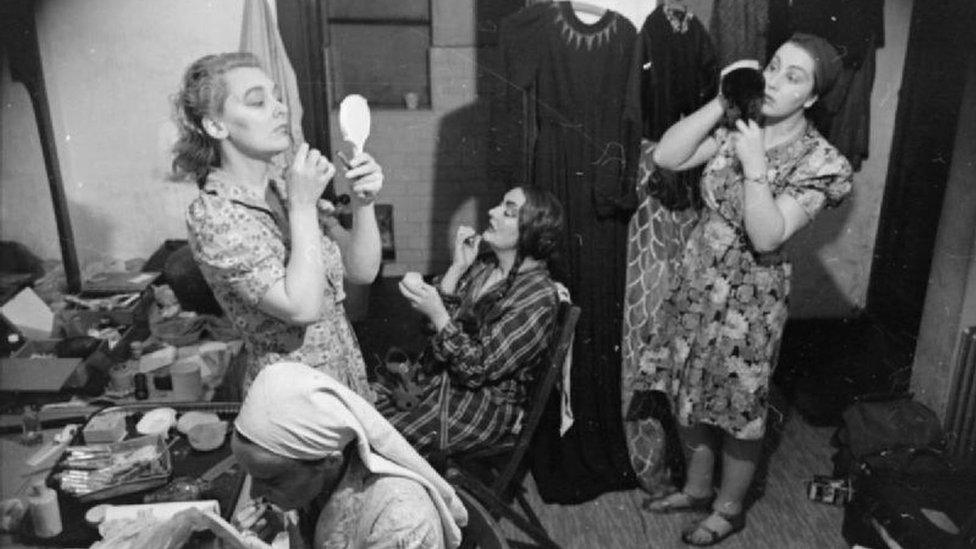

A makeshift dressing room for touring Old Vic actors

London has always been the undisputed heart of British theatre - except, that is, for two years in the 1940s, when the country's top drama, opera and ballet companies were based in Burnley.

It was with both pride and surprise that a programme for a show at Burnley's Victoria Theatre in January 1941 noted that the Lancashire town, built on mills and mines, had suddenly become "the most important creative centre in the English theatre".

Burnley had acquired its somewhat unlikely status when the illustrious performers and crew from London's Old Vic and Sadler's Wells relocated there to escape the Blitz.

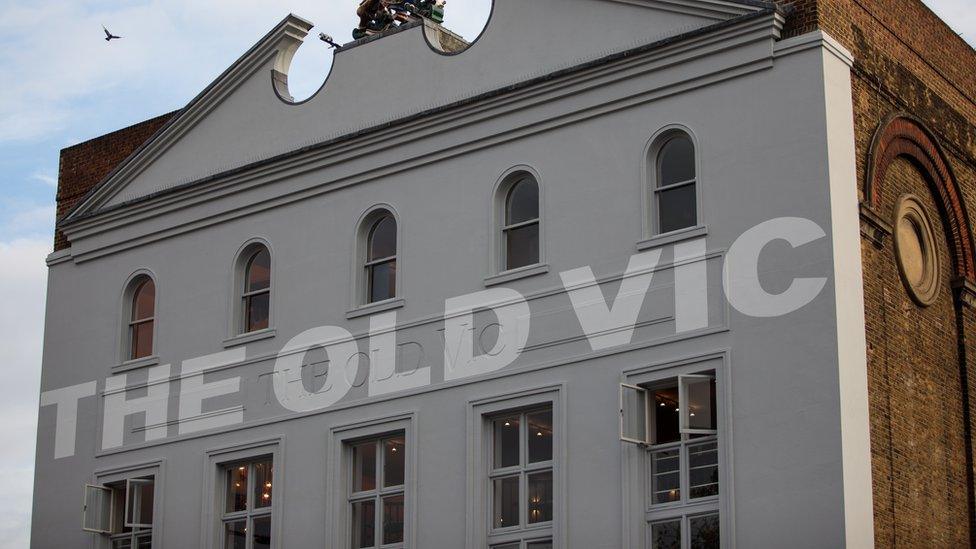

The wartime evacuation of the Old Vic - which is celebrating its 200th birthday on 11 May - remains one of the most curious periods in the theatre's history.

As well as Friday's bicentenary, there's another anniversary - 10 May marks exactly 77 years since the historic Waterloo venue took a direct hit from a German bomb.

Like most London venues, the Old Vic had already shut by then, and the theatre's company had moved north, along with its sister ballet and opera companies from Sadler's Wells, whose home had been converted into a refuge centre.

The theatre staff made their homes in Burnley, with its "dark throbbing factories"

These grand companies made their makeshift base at Burnley's Victoria Theatre, to the delight of local audiences. From there, they also embarked on far-reaching tours to village halls and miners' institutes across the north of England and Wales.

The hub of this activity was an office in a "quaintly decayed slum building" (with an outside toilet) in the town centre, amid Burnley's "dark throbbing factories [and] black forbidding tabernacles", as Vic-Wells director Tyrone Guthrie put it.

But at least Burnley was out of the way of the German bombs, and any apprehension about the companies' temporary home was soon overcome by the warmth of the reception from the locals.

"By the third day, strangers were greeting me in the street, and asking me how I was getting on," the Old Vic's booking agent Charles Landstone wrote in his memoir, Off Stage.

The move was "hugely successful in every possible way", and the thespians enjoyed their stay in Burnley, according to Dr Christopher Fitz-Simon, who published Rise Above!, a collection of Guthrie's letters, earlier this year.

"It's a British thing that they keep smiling in spite of adversity, and the people of Burnley were very welcoming to these peculiar artists that turned up, and these artists were very happy to be out of London because of the bombing," he says.

The unexpected relocation gave the company a chance to take their work to parts of the country that hadn't experienced top-quality drama, opera and ballet for years.

The Old Vic in London's Waterloo is 200 years old on Friday

The programme for the opening show in Burnley in January 1941 read: "For too long London and the great metropolitan cities have owned altogether too much of the cultural life of the country.

"One of the most important and encouraging symptoms of the turmoil which we are now enduring is the dispersal of the treasures and art and culture throughout a wider area of the land, and a wider range of the people."

In the Burnley office, the Old Vic and Sadler's Wells staff organised up to four tours to be on the road at any one time - two drama, one opera and one ballet.

Sadler's Wells ballet - which later became the Royal Ballet - had recently had a narrow escape in Holland, where they were touring when the Nazis invaded.

Upon returning to England, they headed north with dancers including a 21-year-old Margot Fonteyn. However, when they performed in Burnley, Landstone said, "the idea of ballet was still so foreign and strange outside London, that the auditorium did not begin to fill until the second week".

Of the two Old Vic drama companies that went on the road, one was initially sent to south Wales while the other toured north-west England.

Actor Lewis Casson driving the furniture van that transported scenery on tour

The north-west cast included Shakespearean grandee Ernest Milton, Sonia Dresdel (who would become best known for the 1948 Oscar-nominated The Fallen Idol), Esme Church and Alec Clunes (father of Doc Martin star Martin).

In keeping with the wartime spirit, these stars had to make the best of the meagre resources and facilities, and there was little trace of showbusiness luxury or glamour, even by the standards of the day.

Shakespeare's King John, which Landstone noted was "the most important Shakespearean production of 1941", first faced an audience on an "improvised stage" at Lancaster Town Hall.

But "the audience at Lancaster were as enthusiastic as any London first night audience", he recalled.

Landstone also relayed how, after getting lost for several hours driving back to Burnley in the blackout, he was locked out of his digs and ended up sleeping in the office on a bed made of "a dozen Shakespearean costumes which happened to be lying about".

The King John tour ended in Harrogate, where the company, "much to its disgust", was asked to sleep in cabins in the town's swimming baths.

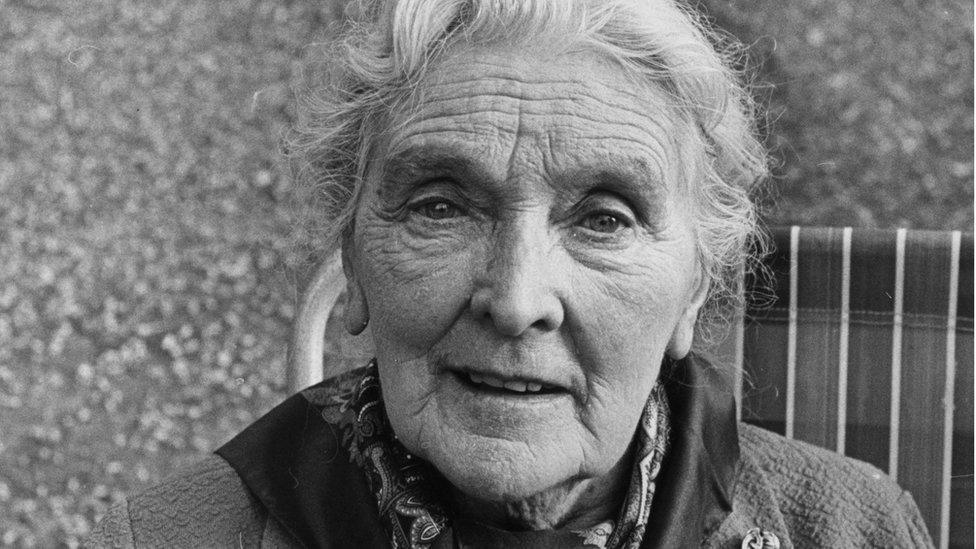

Dame Sybil Thorndike was put up in miners' homes on tour

Meanwhile, members of the Welsh tour, led by Dame Sybil Thorndike - the biggest name in the Old Vic ranks at that time - stayed with mining families, whom the actress described as "wonderfully hospitable".

The reaction of the audiences made an impression on the actress too.

"We've never played to such audiences," she wrote. "None of them move a muscle while we're playing, but at the end they go wild and lift the roof with their clapping. This is the theatre that we like best - getting right in amongst people."

The Welsh crowds would often respond by breaking into song at the end of the show.

Tyrone Guthrie recalled: "I shall never forget the moment when in a mining village not far from Swansea, a packed audience, about 1,000 strong, rose at the end of the performance and fairly lifted the roof off with a hymn - a magnificent, thrilling gesture of appreciation and thanks."

You may also be interested in:

In the crowd in the Carmarthenshire village of Garnant was a 10-year-old evacuee named Patrick Dromgoole. He described the performance as "absolutely electrifying and terrifying", adding: "I knew then that I wanted to be a part of theatre."

He grew up to be a director, staging the premiere of Joe Orton's Entertaining Mr Sloane in 1964. And he passed the theatre bug to his son Dominic, who was artistic director of Shakespeare's Globe from 2006-16.

The Old Vic turned down a request from Vivien Leigh (pictured with husband Laurence Olivier) to join

The Old Vic cast in Wales was meant to have included a 19-year-old Paul Scofield, who went on to become one of Britain's great classical actors.

He turned up for rehearsals, but developed mumps and never performed - although he did leave the mumps behind among several younger members of the company.

Assembling a cast and crew was a constant struggle. Guthrie wrote in 1942 that the opera company almost had to pack up when two "absolutely indispensible" singers were refused further military deferment.

And at one point, he complained that a wigmaker had been denied army leave and so was unable to travel to Burnley (instead, "the little women round all corners have been called up"), while Guthrie trained two girls from the Vic's theatre school as electricians.

But the Old Vic also turned some stars down. Laurence Olivier and wife Vivien Leigh, who was fresh from playing Scarlett O'Hara in Gone With the Wind, took Guthrie a kitten after his cat was run over in Burnley - and tried to persuade him to let Leigh join the company.

Guthrie declined, saying her film star image meant the audience would be there for the wrong reasons, and besides, she wasn't a good enough stage actress.

The Vic-Wells director Tyrone Guthrie kept the show on the road during the war

But the Old Vic and Sadler's Wells didn't need her for their performances to be successful.

The company was crippled by debt when it moved north. When it returned to London in early 1943, as the threat of bombing receded and theatres in the capital reopened, its annual report said the years since 1940 had shown "continuous prosperity".

With the damage to the Old Vic's Waterloo home repaired, the venue reopened in 1950. Burnley's Victoria Theatre went into decline and was demolished five years after that.

Today, there is no professional theatre in the town. However, Burnley's contribution to the theatre landscape left its mark.

Although there had been talk of setting up a National Theatre for years before the war, Charles Landstone wrote that from its first Burnley season, "the Old Vic ceased to be merely metropolitan; its function as a national organisation began to take shape".

Under Olivier's guidance, the National Theatre Company was formed at the Old Vic in 1963, and moved to its present home on London's South Bank 13 years later.

London was once again the magnetic centre of the nation's theatre scene.

In recent years, the National Theatre has ramped up its tours around the country. But it's never been as truly national as when the Old Vic was based in Burnley.

Follow us on Facebook, external, on Twitter @BBCNewsEnts, external, or on Instagram at bbcnewsents, external. If you have a story suggestion email entertainment.news@bbc.co.uk, external.