Obituary: Christo Javacheff, the artist who wrapped the world

- Published

Once a penniless painter on the boulevards of Paris, nobody did art like Christo.

The charismatic Eastern European refugee became world famous for monumental installations, covering huge objects in miles of fabric and rope. Every project was preposterous in concept, taking decades to design, finance and deliver.

He wrapped enormous buildings, avenues of trees, entire coastlines and island chains. Each one cost millions with official permission almost impossible to get. Yet, when finally completed, they were gone again in a matter of weeks.

It was a life of herculean tasks. His determination to see them through never dimmed.

Even in his eighties, he was working on a scheme to rival the pharaohs. A vast stairway to heaven in the deserts of Abu Dhabi, made from 410,000 brightly coloured oil barrels. A final, grand statement larger than the Great Pyramid itself.

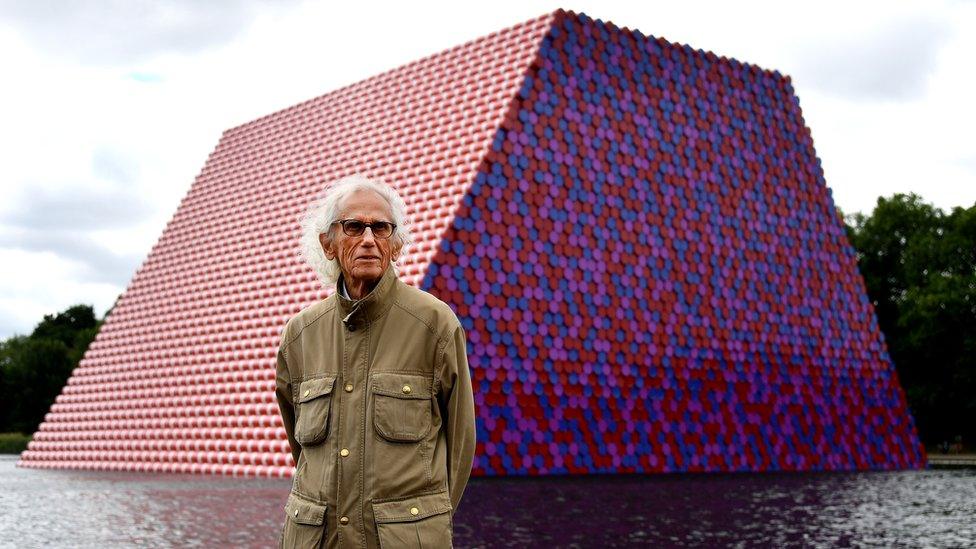

Workers construct The Mastaba, an installation made of plastic barrels, on the Serpentine in London in 2018

Christo Vladimirov Javacheff was born on 13 June 1935 in Gabrovo, a small town in the Bulgarian mountains.

His father Ivan was a chemist who ran a factory making fabrics. His mother, Tzeta Dimitrova, a political activist. Their social circle was one of artists and intellectuals, the household a swirl of radical ideas questioning the boundaries of contemporary culture.

A bohemian childhood, where artistic creativity was encouraged from the start, was constantly disrupted by war. As a boy, Christo saw his country first brutally uprooted; first by the Nazis and then the Russians. Politics, as well as art, shaped his early years.

In 1952, he attended the Art Academy in Sofia. There he was expected to join the Communist Youth and produce realistic, anti-capitalist work glorifying the values of socialism. He turned out the kind of populist propaganda pieces the system demanded. But he found it suffocating.

"The work of art," he would say, "is a scream of freedom."

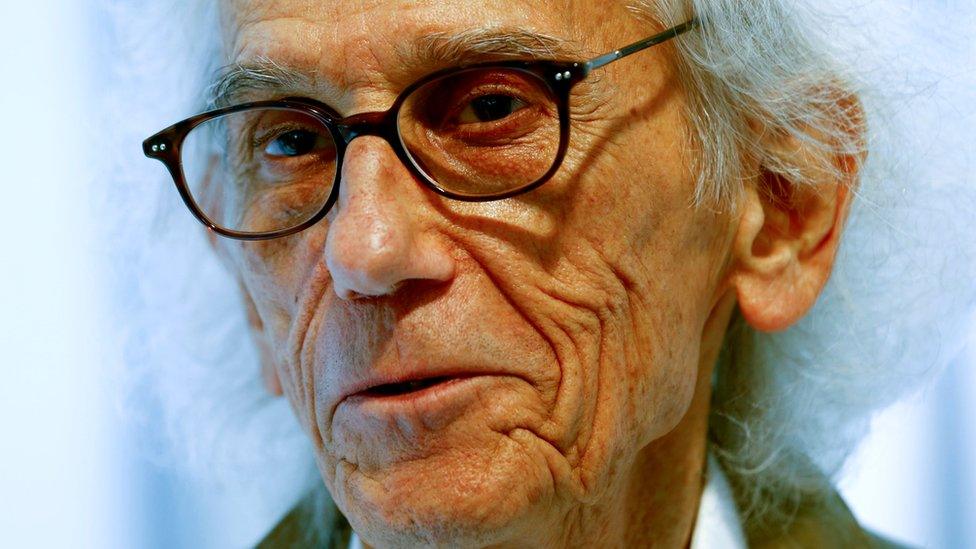

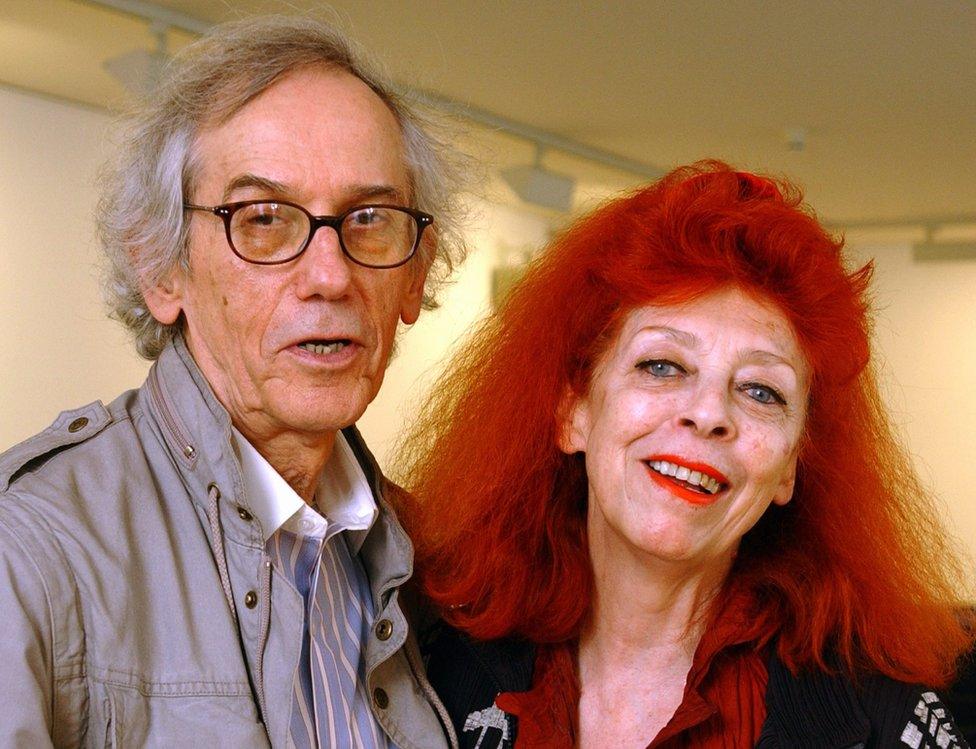

Christo's wife, Jeanne-Claude, was his long time creative muse and business partner

He moved to Prague, got into theatre design and immersed himself in the works of great artists; Miro, Matisse, Kandinsky. When the Hungarian revolution broke out, he saw students and intellectuals like himself dealt with ruthlessly. So he fled.

Bribing a railway worker, he hid on a train taking medicine to Austria. He made it to Vienna but found himself officially stateless - dirt poor and unable to speak the language in a Europe awash with refugees.

Jeanne-Claude

A few years later, he washed up in Paris. He scraped a living painting portraits on the street, something he likened to prostitution. A woman saw an example at the hairdressers and liked it, inviting the struggling artist to her chateaux to paint a picture of her.

The woman's daughter was flame-haired Jeanne-Claude. She would become Christo's wife, his muse, his voice and life-long business partner and creative soul mate.

"Mother's brought home another stray," she thought at the time. Fortunately, that first impression didn't last.

He showed her his 'real work'. In 1920, Man Ray had wrapped a sewing machine with a blanket, appropriating an everyday object and making it art. Profoundly influenced, Christo's garret was stuffed floor-to-ceiling with similar pieces. "My God", she recalled thinking. "This guy is crazy!"

She got pregnant and married a more suitable man but walked out after three weeks. She and Christo were never apart again. Jeanne-Claude's father, a four-star general in the French army, didn't speak to her for years.

Art on an epic scale

What followed was an extraordinary artistic collaboration lasting more than 50 years. At first, their work was credited to Christo alone, feeling that it was easier for one person's name to become established. Only latterly did Jeanne-Claude's contribution get the equal billing it deserved.

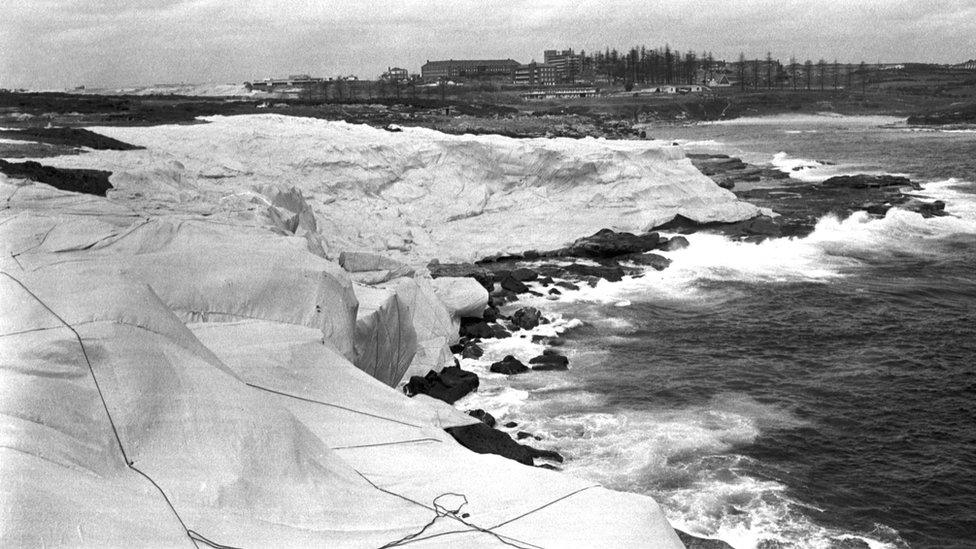

Little Bay, south of Sydney - in 1969, the artists wrapped more than 2km of the Australian coastline

She encouraged him away from small objects in favour of the monumental. In 1962, reacting to the building of the Berlin Wall, they blocked off the Rue Visconti in Paris with a pile of oil drums some 4m high. They begged the police to let it stand for a while but within hours it had gone.

They moved to New York, living in an illegal squat as undocumented migrants. He began producing the sketches and project plans they sold to finance their creations. She took on the logistics and gathered the necessary permissions.

In 1969, they wrapped more than 2km of coastline in Little Bay, Australia. In places, the cliffs soared to more than 26m high. It took an hour to walk from one end of the installation to the other.

Next, they created a fabric fence in California - nearly 40km long and 6m high. Nine lawyers were hired to persuade dozens of local farmers to give their blessing.

"Running Fence", California - the artists built a continuous fabric barrier more than 24 miles long

In 1983, the couple surrounded 11 islands in Miami's Biscayne Bay with more than 600,000 square metres of bright pink polypropylene. The material was individually cut to fit each shoreline. Four hundred people were needed to put everything into place.

Walkways were sewn into the fabric for the public. The 'exhibit' was up for just two weeks, then all 11km of it was taken down.

The absence of meaning

Christo and Jeanne-Claude wanted their works to be joyful and beautiful, encouraging the observer to see the familiar anew. But they refused to give these vast creations any 'meaning' past an immediate aesthetic impact.

The direct impact on the environment was controversial. The couple were careful to recycle everything they used. And none of it was built to last.

Its temporary nature was a key part of the concept. Like the rainbow, its momentary existence was what made it all so wonderful.

"They all go away when they're finished," Christo once said of his creations. "Only the preparatory drawings and collages are left, giving my works an almost legendary character. I think it takes much greater courage to create things to be gone than to create things that will remain."

Up to a point, perhaps. The site-specific creations might have been designed with a fleeting wow factor in mind, but as a body of work they spoke to important themes - impact on the environment, 20th Century human conflict, and the need for perseverance in defence of freedom of expression.

Christo and Jeanne-Claude: How we wrapped the Reichstag

In 1984, they wrapped the Pont Neuf in Paris. It took them nine years to persuade the mayor, Jacques Chirac, to let them do it. Forty thousand metres of golden sandstone fabric was used, chosen to imitate colour of the pavements at sunset.

Next was a $26m project to erect thousands of huge umbrellas - blue ones in Japan, yellow ones in southern California. They were paid for, as always, by the sale of Christo's drawings. They never accepted sponsorship, which would have imposed unacceptable limitations on their art. Three million came to look and picnic in the shade.

Years of lobbying came to fruition in 1995, when the German parliament allowed them to spread 100,000m of fireproof material around the Reichstag. All tied down with 15km of rope.

The most difficult was the one closest to home. Its title, The Gates, Central Park, New York 1979-2005, referred to the years it had taken them to persuade the city to let them do it.

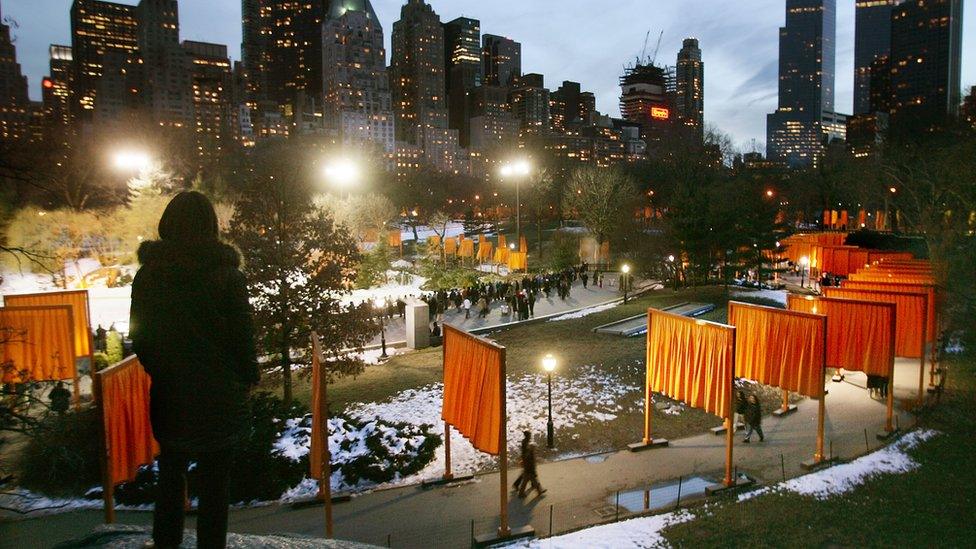

The Gates in New York's Central Park featured 7,500 frames with orange-tinted fabric

In February 2005, more than 7,000 gates made from saffron coloured fabric were finally placed along the paths that wind through the Big Apple's green lung. Together, they formed a fluttering trail 37km long. Five million came to be amazed. A week later, everything was packed away.

Legacy

Jeanne-Claude died in 2009 after complications following a brain aneurysm. For years she had been seen as little more than Christo's business partner and PR manager. In reality, they were two sides of the same creative coin, travelling in different planes so that, if one died, their artistic vision would survive.

Without her, Christo pushed on with their unfinished projects. In 2016, he installed a series of walkways on Lake Iseo near Brescia, Italy. Visitors could walk for more than 3km, just above the calm surface of the waters, from the mainland to the islands of Monte Isola and San Pedro.

The Floating Piers on Lake Iseo, Italy - spectators could walk between the mainland and two small islands

"The most beautiful part," he said, "is about the people walking nowhere. It's not like going to the shop, not going to see your friends. It's really going nowhere."

Despite his claim his work was nothing more than the impact of the aesthetic on the human senses, Christo will be remembered for a body of work that pushed artistic boundaries.

He challenged the idea that sculpture has be something fixed and permanent. He deliberately blurred the line between art and its natural environment. And he did it on a truly epic scale.

His death means we will never see all his visions come to reality. There were plenty that never made it past the drawing board. Even decades of lobbying never let him wrap some of the skyscrapers in New York.

He cancelled a plan to cover the Colorado River, despite spending $14m getting permission, in protest at the election of Donald Trump.

A plan to wrap the Arc de Triomphe in Paris is still set to go ahead next year, but who knows if his scheme in the desert will ever make it from design stage to reality in his absence? It is intended to be 500ft high, with a base the size of the piazza at St Peter's in Rome.

And this one, the only one of all his projects, was designed to be permanent. A lasting tribute to an extraordinary creative partnership whose every scheme was more innovative, ambitious and dauntingly complicated than the last.

- Published1 June 2020