Will Gompertz reviews Epic Games' Fortnite - Battle Royale ★★★☆☆

- Published

So, I was standing there, minding my own business, thinking about what to do next when a young woman who looked a lot like Bjork approached me. She did a little shimmy, jumped up in the air, pushed a shopping trolley my way, and then - without any provocation whatsoever - wiped me out.

And they say Fortnite is a friendly game.

I don't think so.

It might take place on a candy-coloured island reminiscent of a late David Hockney landscape, but there's nothing sweet about the other 99 inhabitants: they want you dead.

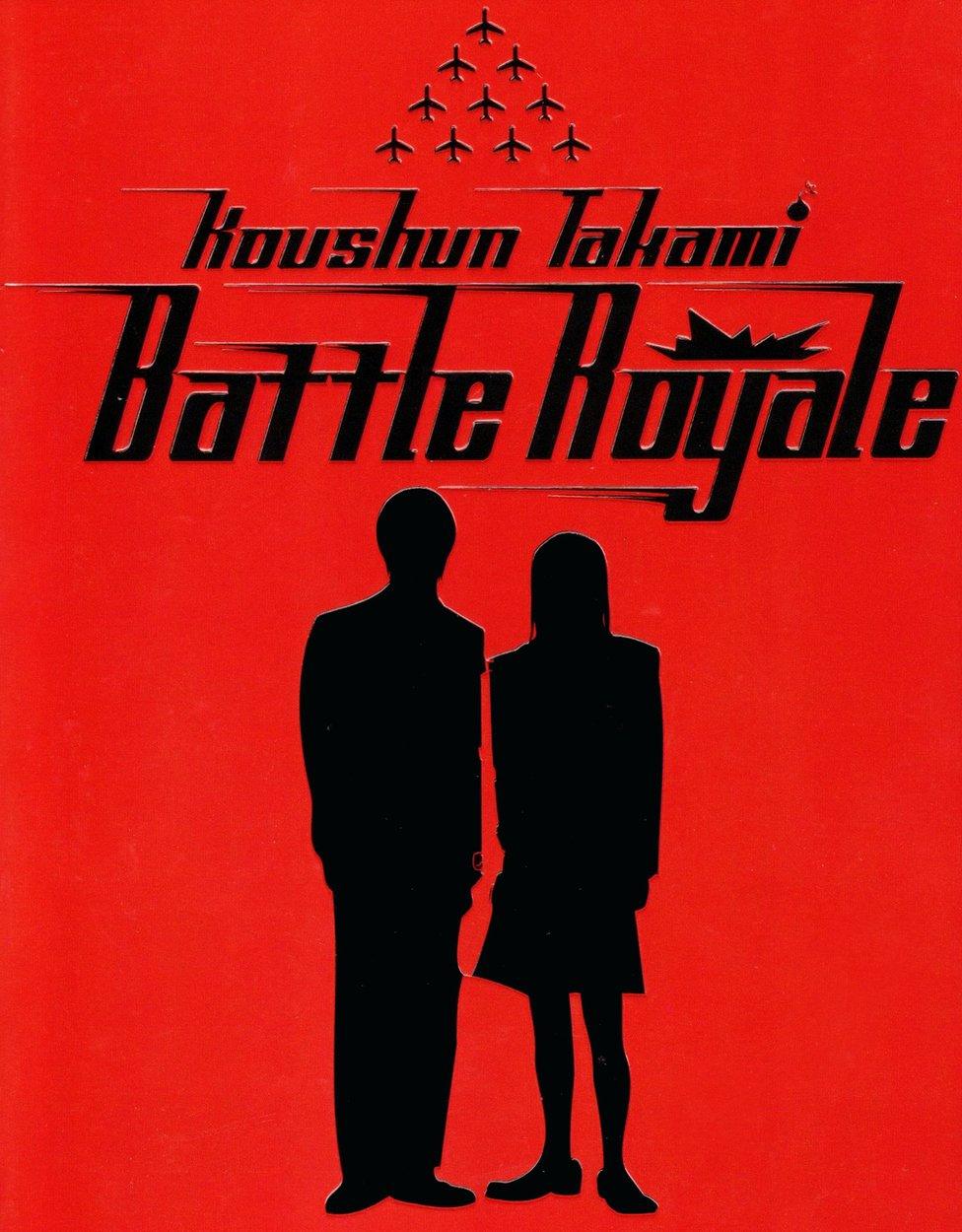

That's the name of the game, in a game that actually takes its name from a dystopian novel by the Japanese author Koushun Takami, which was published in 1999. A year later Kinji Fukasaku, the famous yakuza director, turned Takami's Battle Royale into an extremely violent film, which went on to influence Quentin Tarantino's similarly bloodthirsty Kill Bill movies (Chiaki Kuriyama appeared in both directors' films).

Battle Royale by Koushun Takami

Fortnite is just as deadly but a lot less serious. Or bloody. That's one of its distinctive features. You can go round murdering your opposition with a smile on your face and a flower in your hair - think Lara Croft in pink wellies at Coachella.

The fundamental dramatic structure of Fortnite: Battle Royale is as old as its purple and green hills.

It is basically a last-man-standing game that has been updated by adopting the central conceit of Takami's novel, which is the Millennium Education Reform Act: a nasty piece of legislation passed by the fictional fascistic government of the Republic of Greater East Asia. The Act decrees that each year a class of school children be sent to a deserted island where they will be coerced into killing each other until only one is left: the sole survivor, or put in Fortnite's rather more positive language, Victor Royale.

It is a tried and tested narrative device that's worked for centuries. William Golding (Lord of the Flies), Agatha Christie (And Then There Were None), and Jules Verne (Two Years' Vacation) are but three literary types to have traded on some or all elements of the isolated-group-in-a-desolate place theme.

We've seen it in the Hunger Games, It's A Knockout and I'm A Celebrity. They are all part of the same survival-of-the-fittest genre, which has the sort of in-built jeopardy that makes producers and publishers see dollar signs.

The way in which Fortnite: Battle Royale has adapted the formula is smart, if controversial. The people behind PUBG (PlayerUnknown's Battlegrounds) - an earlier Player-versus-Player (PVP) Battle Royale game, which also whittles 100 contestants down to a single survivor - are claiming their intellectual property rights have been infringed by Epic Games, the company which makes Fortnite.

And for some parents and teachers Fortnite is seen as a triple threat: addictive, expensive (it's free-to-play but you can purchase new outfits "skins" or extras online), and open to abuse.

The latter concern comes from the fact that Fortnite is an internet-based game played online in real-time (in 20-minute sessions if you get to the end), which has social elements allowing players to join forces as a "duo" or "squad". That means you can team up and chat to anybody anywhere in the world, which, of course, has the potential to be taken advantage of by real life baddies (there's an in-game feedback button to report inappropriate behaviour).

All these are important issues but they are not unique to this game. That they have generated so much attention is down to its phenomenal success. Tens of millions of people are playing it, famous YouTubers and pro-game-streamers are making a decent living from talking about it, and a lot of middle-aged people like me are asking what all the fuss is about.

Its appeal is obvious.

The combination of Super Mario's friendly visual language, together with the excitement of a competitive multi-player winner-takes-all eSport, is a compelling propostion.

And it's free (anything you choose to buy won't enhance your chances of winning), on multiple platforms (I played on an iPad), easy to use, and has some nice design touches - such as the free-form building system, with which you can create (design would be overstating it) an instant building or ramp or defensive shield.

Another neat idea taken from the novel is having a device (in this case a gathering storm) to gradually constrict the playing area as the game goes on, thereby forcing those who remain to confront one another.

Fortnite: Battle Royale is a well-made product that has caught the imagination of school children the world over. Which isn't to say that people of all ages can't and aren't enjoying its sugary virtual world, but I am not one of them.

It's OK, but not amazing.

The skydive onto the island that starts the game takes too long, the poppy graphics are irritating, the sound design is dated, and the tools you rely on to survive are crushingly predictable. Added to which, the unsubtle push for players to buy in-game merch is annoying.

For the millions who love Fortnite: Battle Royale, I wish them many happy hours in its brightly coloured world, I am just relieved that the Bjork lookalike saw to it that I no longer have to hang out there.

Listen to Will Gompertz's Heat Map on BBC Radio 5 live on Sundays at 11:00 BST.