The Rolling Stones: How Eel Pie Island shaped the band's career

- Published

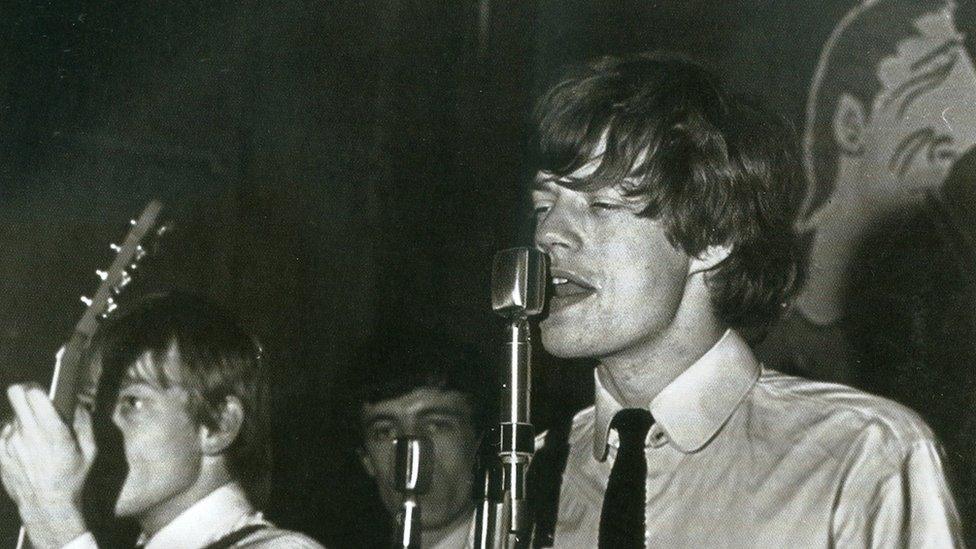

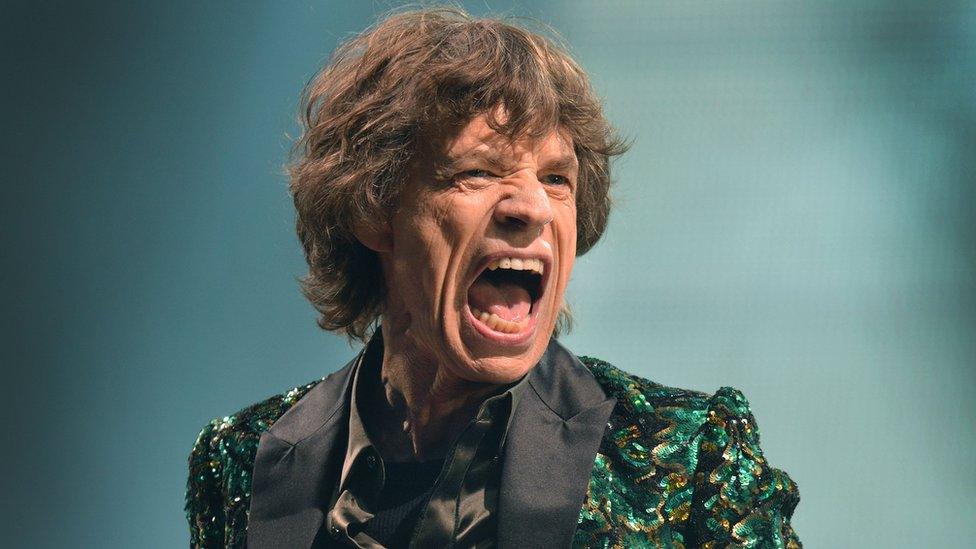

Mick Jagger performing at Eel Pie Island in 1963

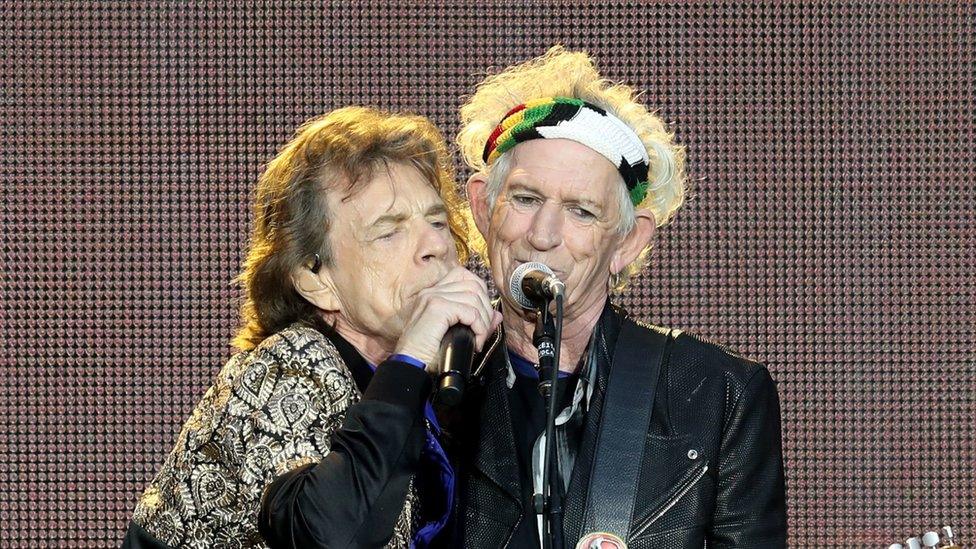

The Rolling Stones' return to Twickenham on 19 June is more than just another tour date - it's a rock 'n' roll pilgrimage five decades in the making.

Back in 1963, exactly 55 years ago to the day, the young band took to the stage just a short walk away from Twickenham Stadium, as part of their five-month residency at the Eel Pie Island Hotel - one of the birthplaces of the '60s revolution.

To mark the anniversary, those involved in the haze of The Stones' riverside gigs in south west London that summer speak to BBC News about their memories and explain just why it was so special.

'Match made in heaven'

Tucked away deep within the enigmatic island, the hotel - built in 1830 - began life as a luxurious three-storey riverside resort, popular with holidaymakers in search of tranquillity.

Despite its apparent calm, it also contained the perfect ingredients for teenage rebellion - a ballroom, sprawling bar, and, most importantly, a sprung dancefloor. Rumours swirled of raucous dance evenings throughout the '20s and '30s, before the venue fell into decades of decay.

But even throughout the wilderness years, these elements remained intact, dormant and ready to be rediscovered. When the rhythm and blues invasion gripped popular culture it proved a passionate match made in heaven.

From 1956, the hotel played host to over 900 gigs. In the words of one early regular, Janet Wedler, it became a "mecca" for fervent teenage desire - soundtracked first by live performances from jazz greats such as Acker Bilk and Ken Colyer, and, by '63, the sound of The Yardbirds' blues.

The Stones' residency that summer coincided with the release of their debut single Come On - a rallying cry that chimed with the youth's insatiable yearning for change.

Allow YouTube content?

This article contains content provided by Google YouTube. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read Google’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

The seeds of the hotel's transformation lay at the hands of Michael Snapper and Arthur Chisnall.

The pair worked together at Snapper's Corner - a Kingston emporium of oddities, furniture and vinyl records, reflecting the flamboyant spirit of its owner.

After visiting Eel Pie Island, Snapper bought the hotel, recognising its potential.

The hotel, originally built in 1830, hosted an estimated 900 gigs

Following the success of some informal jazz nights, Chisnall stepped in, offering to pay the bands and legitimise the venue as a club.

Snapper "saw the dollar signs" and "bit his hand off" says Pete Watt, a journalist and historian at the Eel Pie Island museum.

"He wanted to help people further themselves," Watt explains, adding that Chisnall had realised that music was "the best way to unite young people".

Speaking on Radio 4's The Eel Pie Island Hotel, shortly before his death in 2006, Chisnall said: "I didn't know what impact I was having on the music scene. You've got to remember that my job was to create a world for people and I created that world."

The creation of this alternative reality was galvanised by the bridge that Snapper built in 1957 to replace the ferry service over to the island.

The train line from Windsor to Twickenham was affectionately renamed the Eel Pie Special. For Ray Chellingworth, an Eel Pie regular, making that journey felt like "leaving ordinary life behind".

Hidden down a winding path, the hotel's faded grandeur made it "incredibly unusual - certainly not a normal jazz club or bar".

The bridge, funded by Snapper, transformed access to the island and the hotel, previously only reachable by ferry

Its Wednesday night gigs - which by '62 boasted jive nights featuring Screaming Lord Sutch and the Rebel Rousers - became a huge success, eulogised about by teenagers across London and beyond.

Parental concerns about the hotel intensified amid numerous reports of cannabis raids. It was a time of establishment warnings about the advent of the teenager - a new concept, but this reaction only served to strengthen the hotel's appeal.

The venue played on this mythology. Regular attendees could apply for a passport which would grant entry to Eelpiland, while everyone received an entry stamp - a pledge of allegiance.

However, one night in early '63, Chisnall arrived to find the venue almost deserted. The reason? The nearby Station Hotel in Richmond had The Rolling Stones performing.

'I'm with the band, man!'

A visit to one of their shows convinced Chisnall he needed to act quickly to catch the crest of the cultural wave.

Even at this early stage in their career, The Stones had already become "the great sensation you must pay to see" says Keith Altham, who went on to represent the band from '64.

Chisnall did just that, offering the band an unheralded five-month Wednesday night residency, from April to September, at £45 a show (with the option for them to continue playing in Richmond every Sunday).

Their takeover quickly elevated the club night to dizzy heights.

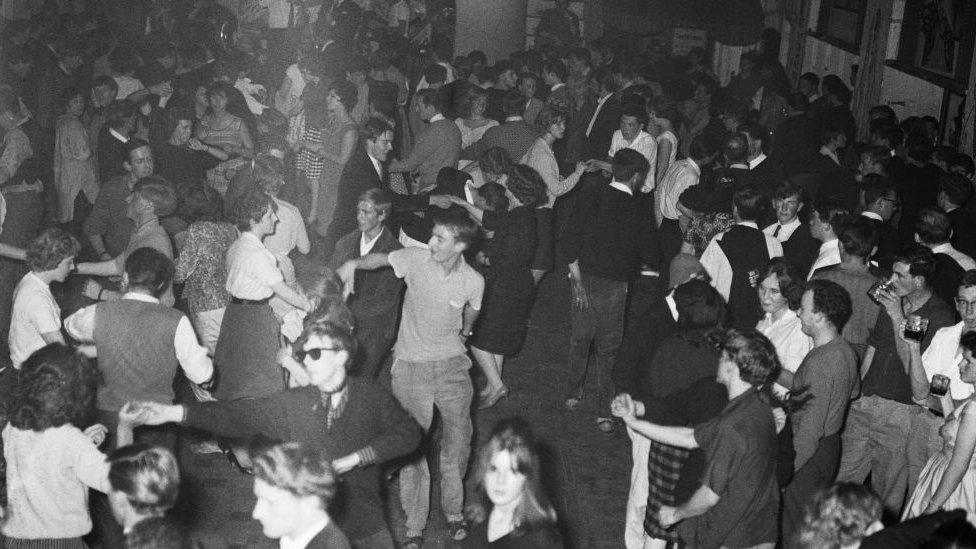

The hotel's sprung dancefloor always kept people moving

Stuart Gurney, who worked on the door at the time alongside Chisnall has never forgotten the sudden, seismic impact the band made.

In a matter of weeks, he admits he went from not knowing who Mick Jagger was to realising he was watching history in the making.

"During one of their first shows, I actually stopped Mick from entering as he didn't have a stamp and I wasn't aware who he was.

"It was only when he said 'I'm with the band, man!' that I realised he was the lead singer," Gurney says.

'At breaking point'

Lengthy queues formed outside the venue, with the ballroom's young rock lovers "packed in like sardines".

"We even had to begin turning fans away, because the venue - always dilapidated - really was at breaking point," he remembers.

The reason for the band's popularity lay, Gurney says, in their "energy and basslines" orchestrated by Brian Jones, Bill Wyman, Keith Richards and Charlie Watts on drums - and the fact they were "just so bloody good".

Chellingworth had a similar experience: "My friends and I were initially disappointed, as we'd gone to see The Yardbirds, but the Stones took their place.

"Mick was typically Mick, he hasn't changed, I remember dancing like crazy."

A strong communal spirit, overseen by Chisnall, kept the hotel's club nights largely free from trouble

The hotel's sprung dancefloor made it almost impossible to stand still. This only added to the atmosphere of the environment - hot, smoky and full of irrepressible energy, as ale flowed freely.

The top floor was meant to be closed off for health and safety reasons, but visitors often made their way up to find some privacy, shall we say.

"There was even a room upstairs for the bands, and girls got up there. That was where the action happened," says Gurney.

Over time, the venue witnessed the teenage years of numerous future stars from Ronnie Wood and his brother Art, to Rod Stewart.

"Rod was far from a big name then," adds Gurney. "He liked a good time but I paid his entrance fee once!"

In the years that followed the venue played host to a vast array of names, until in 1967, the council revoked its licence.

'Rock history gone forever'

Faced with a £200,000 bill for repairs, underpinned by the floor finally falling in (causing one girl to break her leg), Chisnall felt he had no choice but to part ways with his business partner.

Snapper eventually found a new partner in Caldwell Smythe, otherwise known as Colonel Barefoot.

But while the roster of bands continued to increase in calibre under his watch, featuring Pink Floyd, Joe Cocker, David Bowie, and eventually The Who, Snapper was forced to concrete over the dancefloor for safety reasons.

"It lost its charm and became just another venue," says Watt.

Mick Jagger (L) and Keith Richards (R) are currently on tour for the Rolling Stones' No Filter Tour

Towards the end the hotel became an impromptu hippie commune, until in 1971 - just after Snapper had put in redevelopment plans - it burnt down in a mysterious fire.

"No-one knows for sure what happened," says Watt, but "the long-standing slice of rock history was gone forever".

Looking back, could the heady environment Chisnall created exist today? Gurney doesn't think so.

"Health and safety would have a heart attack, especially given the riverside surroundings," he says. "Many people fell in drunk."

While Chisnall enforced few regulations (aside from a strict anti-drugs policy), everyone bought into his vision through a "shared love of music and new experiences".

Ahead of The Stones' return to Twickenham, Gurney hopes "Mick says a few words about Eel Pie", adding: "After all, that's where it all started."

Follow us on Facebook, external, on Twitter @BBCNewsEnts, external, or on Instagram at bbcnewsents, external. If you have a story suggestion email entertainment.news@bbc.co.uk.

- Published15 May 2018

- Published26 February 2018

- Published12 July 2012