Frida Kahlo: Will Gompertz reviews new show at London's V&A ★★★★☆

- Published

If you're anything like me, I bet I know what you do with those few fleeting moments of spare time you have (between watching episodes of Love Island or World Cup matches).

You reach deep into your bookcase and pull out your much-thumbed 1990 edition of The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Art & Artists. Because why wouldn't you?

It's a terrific read, packed with expertly abridged biographies of Old Masters and pithy explanations for arcane techniques like encaustic painting (a favourite of Jasper Johns).

No wonder we keep going back to it.

But, like all things, it is not faultless. There is one surprising and glaring omission. Open it up at page 239, look under K, and you will discover there is no entry for Frida Kahlo beyond the words: "see RIVERA, DIEGO".

Frida Kahlo with her husband, Diego Rivera, circa 1945

Rivera, who was Kahlo's husband, is afforded a lengthy entry in which he is described as a "…most celebrated figure" and "leading artist", who made art "glorifying the history and people of the country [Mexico]…".

It is not until you reach the bits-and-pieces information right at the end that we learn, "He had numerous love affairs and was three times married, his second wife being a painter, Frida Kahlo (1907-54)."

Not "the" painter, or "fellow artist", but simply a glib dismissal as "painter".

Given Kahlo's current status as one of the most famous and revered artists of the 20th Century, it seems like the most extraordinary oversight. And so it is, but it is also instructive. We learn at least three things about the art establishment from the omission:

The tendency by (predominately male) art historians to erase female artists from the accepted canon.

Frida Kahlo has only relatively recently been anointed by establishment curators in Europe.

The art world's limitless talent for post-hoc myth making.

The idea that any reputable art history directory would omit Frida Kahlo today is laughable.

Indeed, the current edition of The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Art & Artists boasts a reasonably lengthy entry under her name. But, once again, it is revealing.

The Rivera entry begins with his art credentials: "Mexican painter, the most celebrated figure in…fresco painting that is Mexico's most distinctive contribution to modern art."

Whereas Kahlo's entry begins: "Mexican painter. In 1929, when she was still at school, she suffered appalling injuries in a traffic accident, leaving her a permanent semi-invalid, often in severe pain."

It is her personal story, the bolstering of her myth that is deemed the most important thing to say about her, not the nature or style of the paintings she produced, which is surely the reason for the entry in the first place.

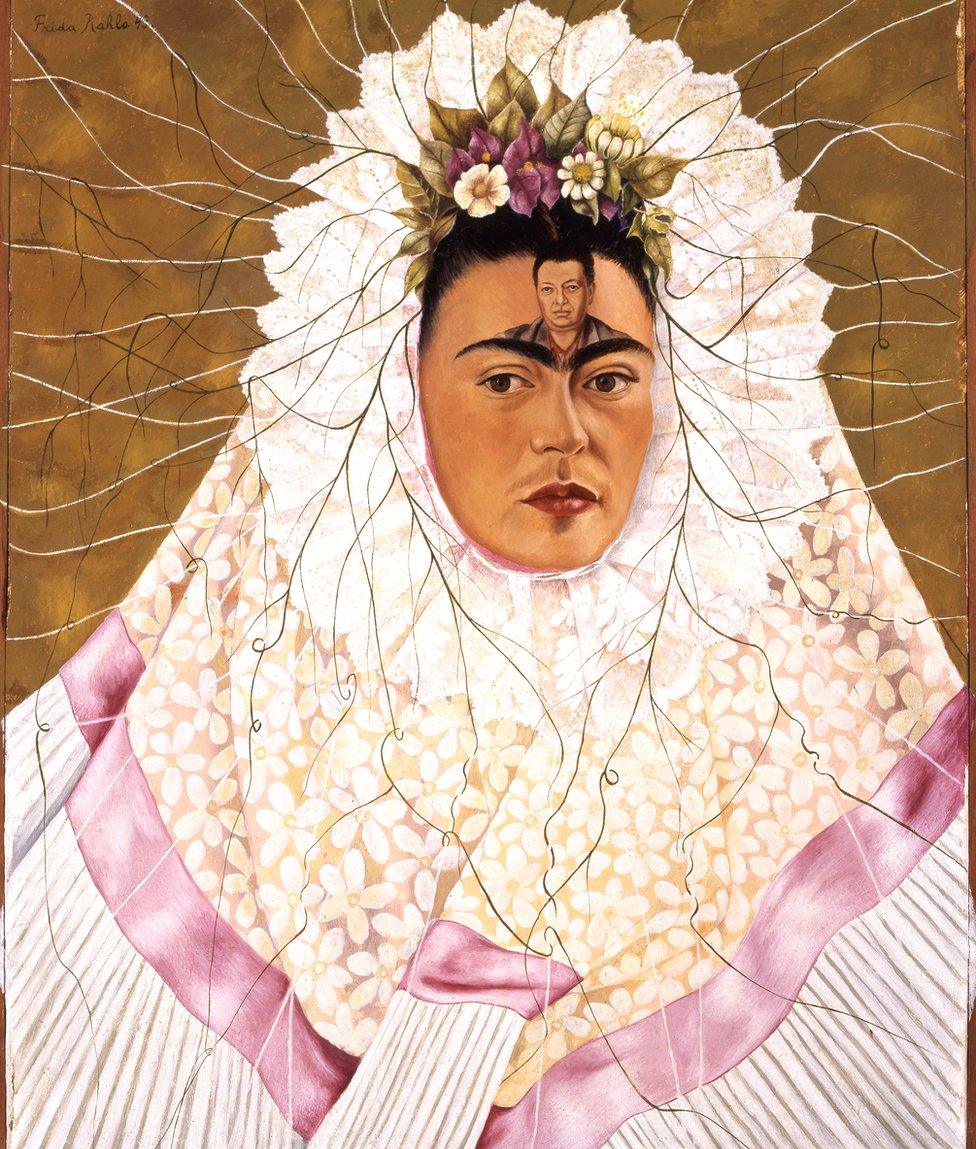

Self-Portrait as a Tehuana, 1943

So, here we are, more than 60 years after her death aged 47, totally fixated by the cult of Kahlo: a packaged personality that all but obscures what we should really care about, which is her work.

The exhibition at the V&A is a typical case in point. To their credit, the curators are not trying to hide the fact that they are selling a show based on the artist's iconic image rather than her paintings, by giving it the title: Frida Kahlo, Making Herself Up.

To be honest, my heart sank when I was told the premise of the show was to look at how she constructed her personality and why. Here we go again, yet more myth making. Couldn't we examine how she made her work and why instead? Wouldn't that be more interesting?

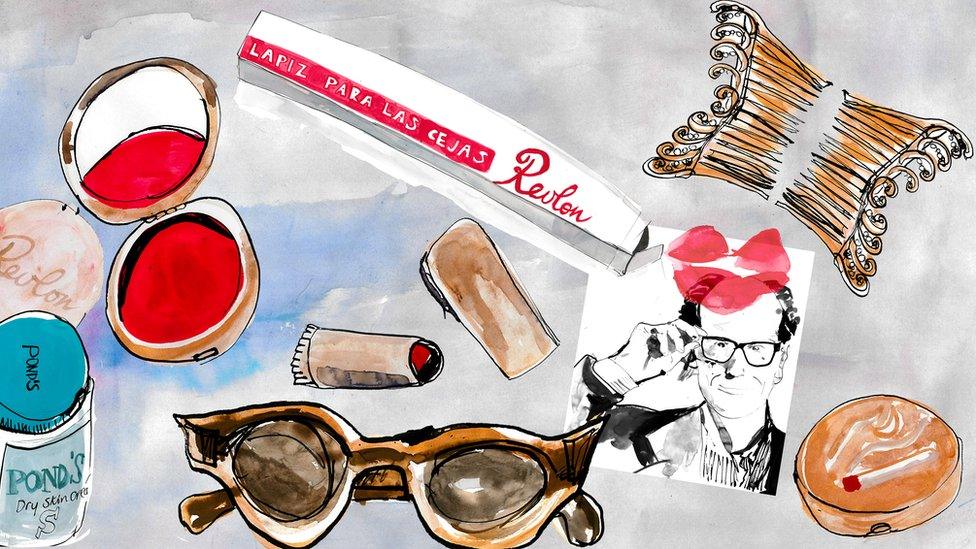

But as I walked around the show, the vast majority of which is made up of objects that were locked away in the bathroom of her house in Mexico for half a century (more myth making), it became increasingly apparent that in Kahlo's case there is no separation between art and artist: they are one and the same.

Frida Kahlo endured multiple operations, and had to wear orthopaedic corsets, including this one made of plaster, which she painted and decorated

It turns out the show isn't a hackneyed hagiography at all, but a revelation.

From the early family photograph in which an androgynous-looking Frida is wearing a three-piece suit, to the image of her sitting on a Manhattan rooftop dressed in her spectacular Mexican clothes and smoking a cigarette, it becomes crystal clear that from her late teens onwards, Frida Kahlo was essentially a performance artist.

Frida on the roof-deck in New York, 1946

The image we have of her, the public image she developed (even when pictured in "private"), the Frida on show here, is as much an artwork by her as one of her paintings.

The traditional Mexican clothes she wore, the indigenous jewellery she collected, the photographs for which she posed, the monobrow, the moustache, her attitude: every detail was meticulously considered and curated by the artist to communicate to us her ideas, ideals, and feelings.

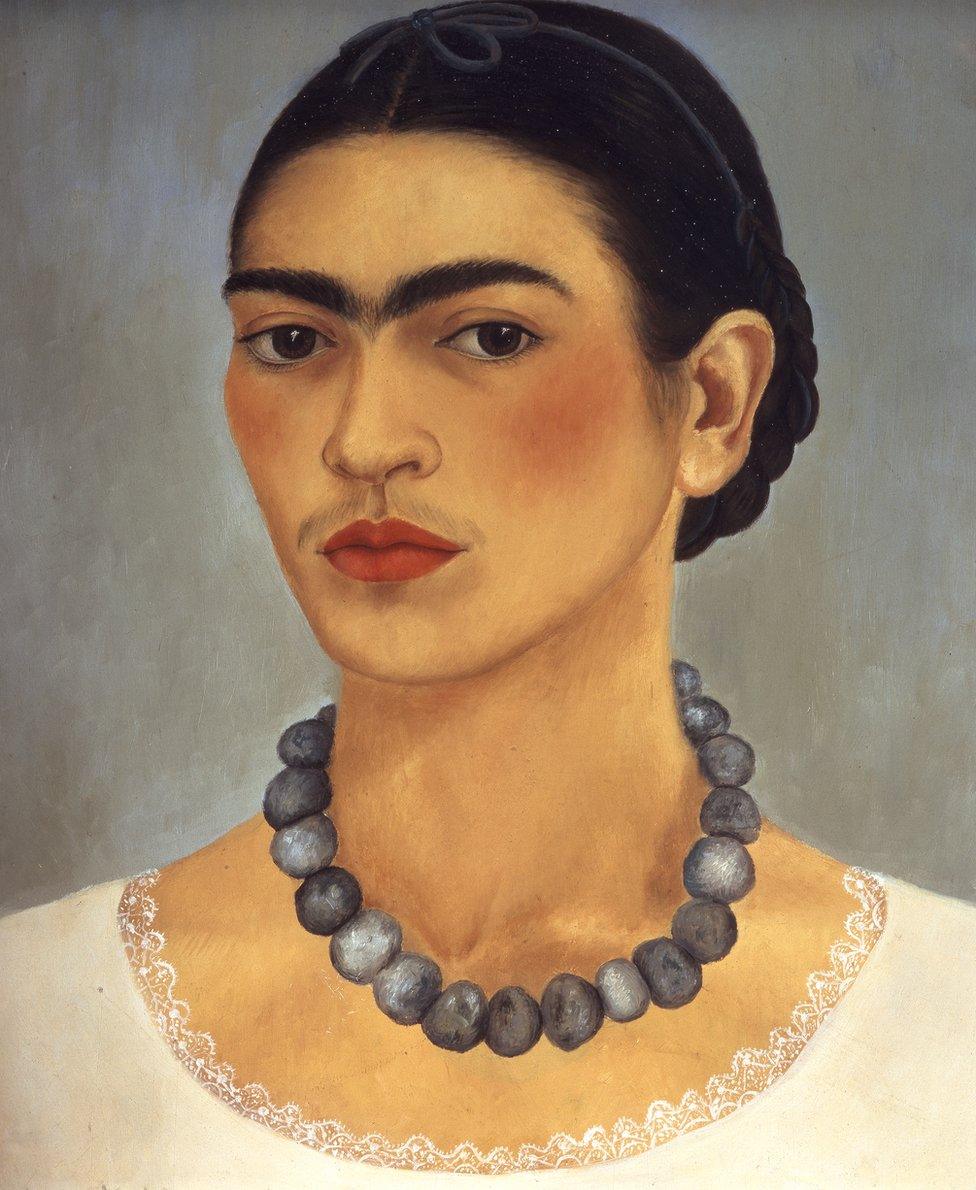

Self-portrait with Necklace, 1933

There is clearly also a performative aspect to her paintings; in so much as she is usually the main protagonist acting out the picture's narrative. The sense of her using her body as a canvas is most explicit in the way she decorated the plaster corsets and prosthetic leg on display in a gallery full of her medicines and medical equipment.

One of the most intricate objects in the collection is Frida Kahlo's prosthetic leg with leather boot, and silk appliqué with embroidered Chinese motifs, 1953

And so the more this exhibition seeks to unmask the 'real' Frida the further she disappears behind her defiant façade.

By the time you emerge from the theatrical last room of dresses and shoes, you know for sure that you have absolutely no idea who the real Frida Kahlo was.

You only know what she wanted to show: what pain looks like, what Mexico looks like, what gender looks like; what love looks like.

It is her agenda, not ours.

We can mythologise her all we like, but to do so is to miss the point. As this exhibition makes abundantly clear, maybe not entirely intentionally, Frida Kahlo only ever revealed one thing to us: art - in all her guises.

Frida Kahlo, 1939

Listen to Will Gompertz's Heat Map on BBC Radio 5 live on Sundays at 11:00 BST.