Sharp Objects writer Gillian Flynn on why she wants to show recognisable women

- Published

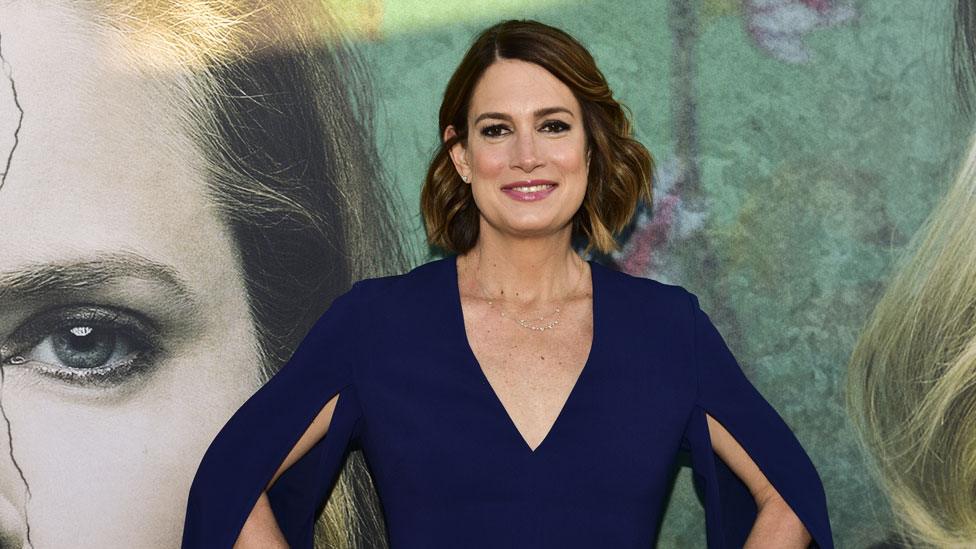

Gillian Flynn at the Sharp Objects premiere

Gone Girl author Gillian Flynn explains why she wants to see "every kind of woman" represented as the TV version of her novel Sharp Objects reaches the screen.

When Gone Girl became a best-seller, some people were taken aback by its protagonist Amy, played by Rosamund Pike in the film.

The problem was, she just wasn't... nice.

And that's exactly the way Gillian Flynn, who wrote the book on which the 2014 film was based, wanted it.

It wasn't the author's first rodeo either, having set out her stall creating dark, complex female lead characters with her 2006 debut Sharp Objects.

That novel has now also been adapted the screen. It stars Amy Adams as Camille, a journalist with a troubled past who is sent to her hometown to report on a young girl's murder.

So why did Flynn decide to write such disturbed, and at times disturbing, characters? Well, you can blame so-called "chick lit".

'Get the guy, get the shoes'

"I wanted to write about a dark, damaged, screwed-up, troubled female protagonist," she tells BBC News. "Those male characters were everywhere you looked - and have been for hundreds of years in literature. That's just been the archetype.

"I just didn't see enough of that anywhere, so I just thought 'I'll write it'. At that time, it was the very height of chick lit, with books like Bridget Jones's Diary.

"They're all great books and all fun - get the guy, get the right shoes and live happily ever after. It was driving me slowly insane.

"I sat down to write the opposite. I mean, you never hear Camille talking about her shoe-wear."

Amy Adams plays the troubled Camille in the Sharp Objects series

That's putting it mildly. The Camille we see in the series is battling demons from her past - including her fraught relationship with her mother Adora, played by Patricia Clarkson - and bearing the scars of self-harm.

Flynn, who has written three episodes and is a producer on the HBO series, admits things have changed since her debut, with dark, complex characters now "much more common".

But, she says, "I've written them ever since. I just can't seem to stop. I remember writing the second one, thinking: 'I'd better not write another troubled, dark narrator'.

"But it's what I'm interested in. The more types of women we see is what's important."

Flynn admits that Gone Girl "opened the door" to a wider variety of female characters.

Camille with her mother Adora, played by Patricia Clarkson

"And it made a lot of money!" she laughs. "Anything that makes a lot of money will make publishers say 'we want more of that'.

"It's really important that it's talked about - let's see more of every kind of woman. That's why I wrote her in the first place. There are women in pain, screwing up, struggling and yet managing to keep their heads above water.

"For any woman out there thinking there's a person they're not seeing in literature, just write it! That, to me, was the whole point."

'No cardboard cut-outs'

So how does Flynn answer the criticism she's received from some quarters that she's been "misogynistic" in her portrayal of women?

"I think it's misogynist to say it's misogynist to write about bad women," she says. "Anytime you tell a woman what she can and can't write about, that's misogyny.

"I mostly ignore it. It's such an insane thing to say, as if you're too delicate to bear the idea of a negative portrayal of a woman."

Literature has moved to represent women in a way that films and TV often haven't, Flynn muses. "I think they have a long way to go," she adds.

"It's important to be able to look on a screen, and turn pages, and see a recognisable human woman, rather than a cardboard cut-out."

Flynn with Adams, Clarkson and series creator Marti Noxon

Not that there's any chance of Adams being described by anyone in such a way. Flynn singles the Arrival star out for praise.

"She has this incredibly unique combination of vulnerability, but also steeliness," she enthuses. "You see her being able to show empathy on screen but also, you don't worry about her too much - you worry about her just the right amount.

"You don't think she's ever going to break; she has this unbreakable quality. Camille is a very damaged human being, but you're not so concerned that you can't bear it.

"You have a realisation this is a woman who has been through a lot."

'Hooking the umbilical cord in'

The mother-daughter relationship at the centre of Sharp Objects was "very important", says Flynn.

"It's something else that I wasn't seeing enough of in literature. I think there can be something about that relationship that's really toxic, and symbiotic in a very odd way.

"Camille has stayed away, and now she's hooking the umbilical cord back in, into that sick place. And she has to do it to figure out what's going on."

Seeing Adams and Clarkson together were "some of the most disturbing and hard-to-watch scenes", the author admits.

Clarkson and Adams have six Oscar nominations between them

"Because Camille was so young when things happened and things were going wrong, she's never really been able to process it or confront it - because the truth is so horrifying," says Flynn.

"She's buried it, but that pain wants to bear witness. I've certainly gone through periods of deep psychological pain.

"That feeling when you're in such terrible pain and you can still manage to walk around and slap on a smile. It's a horrifying and frightening thing.

"You want to scream - 'can't you see how much pain I'm in? Is no-one seeing this?' For Camille she was cutting, because she wanted that pain to be seen, to be witnessed."

'Echoes of myself'

Flynn admits that much has changed for her since she wrote Sharp Objects 12 years ago - and says the process of bringing it to the screen was much longer than was the case for Gone Girl.

"I wrote it in my late '20s, early '30s, and I was living in a different city," she explains. "I hadn't even met my husband. I can hear the echoes of myself in there, from a different time period."

The author admits she hasn't read the book since then, saying she tends not to read her own work once it's finished.

"So to revisit it and see those characters come to life again... it's like a carnival, being put on in front of your eyes," she smiles.

Sharp Objects is available on Sky Atlantic and Now TV.

Follow us on Facebook, external, on Twitter @BBCNewsEnts, external, or on Instagram at bbcnewsents, external. If you have a story suggestion email entertainment.news@bbc.co.uk, external.

- Published4 January 2018

- Published30 December 2017

- Published21 April 2017