Rudolf Nureyev: How the dance legend continues to inspire

- Published

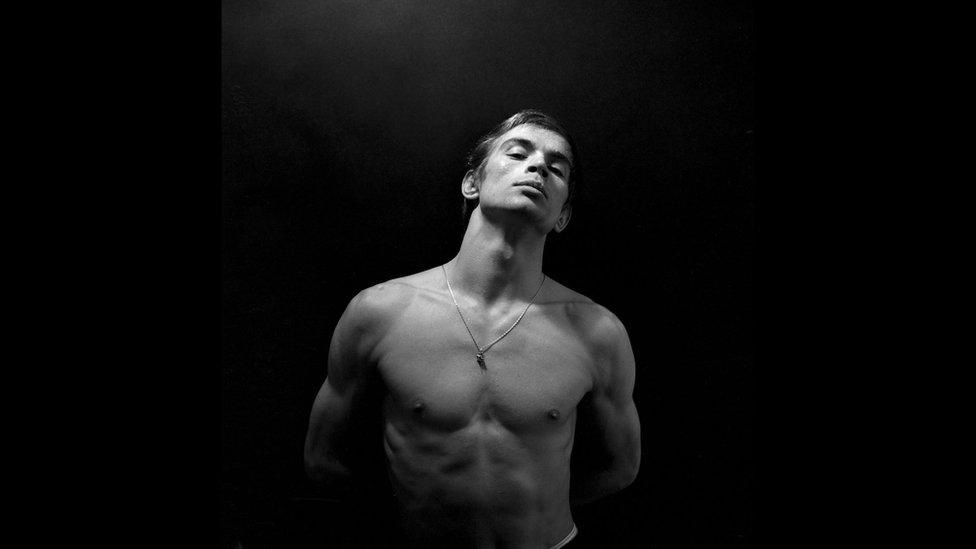

Nureyev's dancing ability and good looks gave him star quality

The Russian ballet star Rudolf Nureyev would have been 80 this year, which also marks the 25th anniversary of his death. Yet, with a new documentary about him just out and a feature film due for release, the fascination in the dance legend clearly still lives strong.

In 1974, Nureyev - at the height of his fame - hot-footed it from a performance at New York's Lincoln Center onto the set of an American TV chat show hosted by Dick Cavett.

There was rapturous applause from the live audience.

"That's more than Mick Jagger got," Cavett said when the clapping finally died down.

Nureyev was dressed in a shimmering snakeskin jacket and purple, crushed velvet trousers.

The clip of this moment in TV history appears in the cinema documentary Nureyev, and underlines just how the Soviet-born dancer, with his good looks and impressive physique, had achieved rock-star-like status in the West.

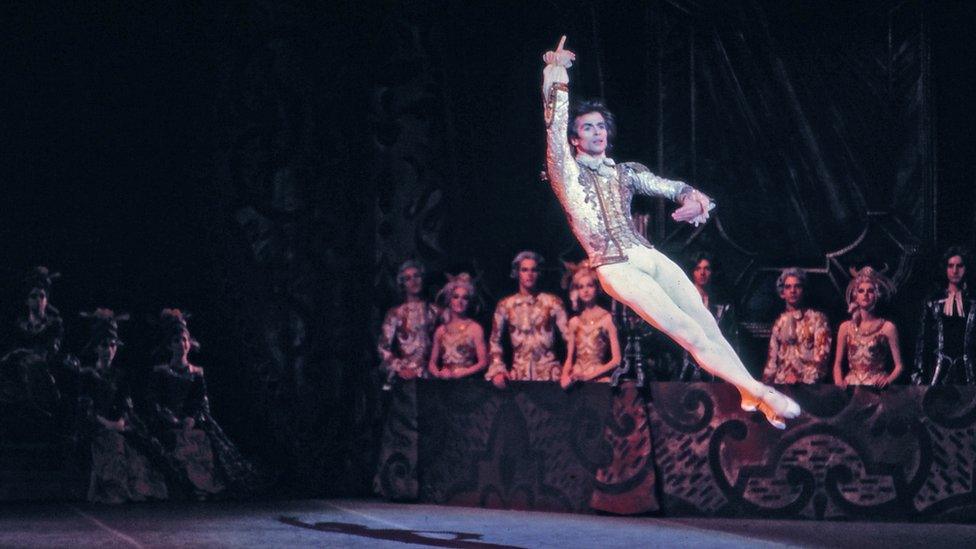

Nureyev was known for his athletic performances

"He was enormous. In my generation, everyone knew who he was," says David Morris, who is in his early 50s and co-directed the documentary with his sister Jacqui Morris.

It shows how Nureyev, as well as dancing on some of the world's biggest stages, crossed over into popular culture. He was on magazine covers, newspaper front pages and in gossip columns, and photographed with figures such as Elizabeth Taylor, Jackie Kennedy and Princess Diana.

He even appeared on the Muppet Show, performing Swine Lake with Miss Piggy.

Nureyev mixed with many famous people, including the Hollywood star Elizabeth Taylor

But, David adds: "Dance is ephemeral and his celebrity sort of died with him."

The brother and sister say they want to introduce Nureyev to new audiences who know little or nothing about him.

"All eyes are on Russia now and we're talking about the Cold War again," says Jacqui.

"What we try to do in the film is introduce elements of the Cold War to a younger audience," she says.

"But always keeping it about him," David adds.

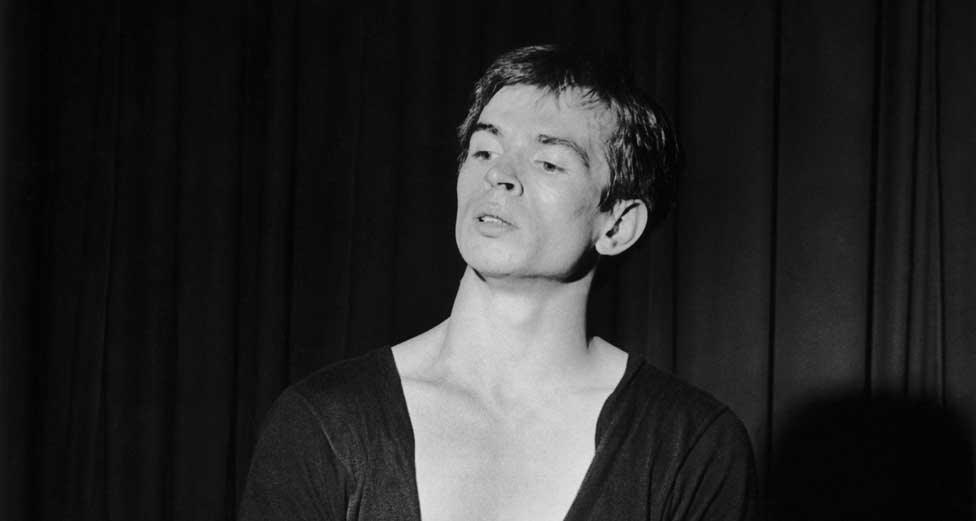

One of the elements is the propaganda coup that Nureyev's defection in 1961, while on tour with the Kirov Ballet in Paris, represented for the West. He defected as he was about to be sent home for breaking the company's rules.

It came just two months after the Soviet Union had got one over the West by sending the first human - Yuri Gagarin - into space.

Nureyev was already one of the Kirov Ballet's star performers when he defected in 1961

"They were on top of the world and the worst thing that could have happened was a high-profile defection," says Jacqui.

Nureyev and his family paid a heavy price. He was only allowed back in the USSR more than 25 years later when his mother was dying, while his Soviet friends' careers were made to suffer.

The film uses archive footage, contemporary interviews with people who knew him and re-enactments by dancers to trace the story of Nureyev's life.

It follows him from his humble beginnings in provincial Russia, to Leningrad where he joined the Kirov and to his untimely death from an Aids-related illness in 1993 at the age of 54. It contains 15 minutes of what the directors say is previously unseen archive footage they unearthed.

It is not the first documentary about Nureyev, and a feature film about him, The White Crow, is due out next year, but it gives a real insight into Nureyev the man, not just the dancer.

One of the most moving scenes is when he is reunited in Russia in the late 1980s with his first ballet teacher, Anna Udaltsava, who took him under her wing when he was 11.

By then she was 100 years old and, on realising who has come to see her, the documentary sees her grasp hold of his arms and say, "My boy". Nureyev seems as touched by that recognition as by any of the recognition he'd received on the world stage.

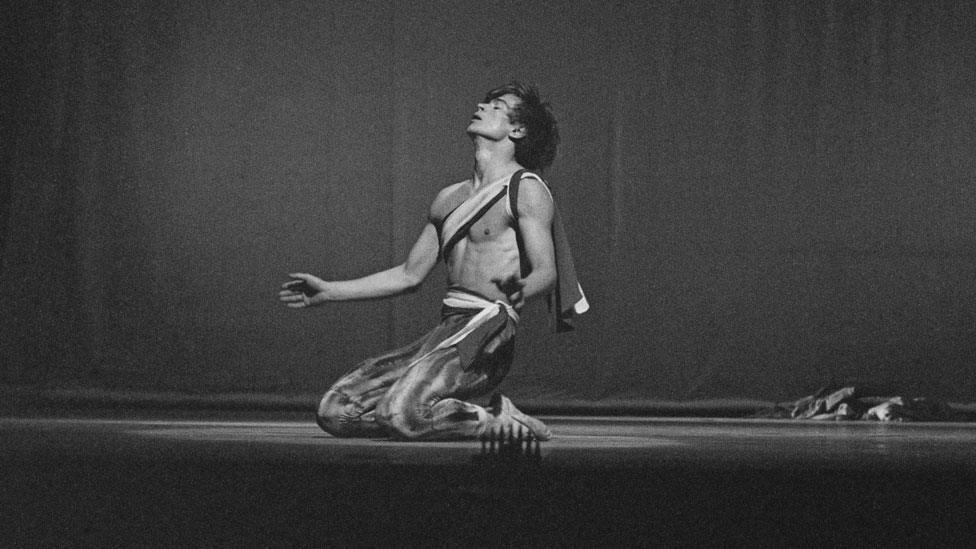

The film argues Nureyev changed the role of the male ballet dancer from mainly supporting the ballerinas to being allowed to take centre stage.

Nureyev was invited to perform in London by Dame Margot Fonteyn

"It was like seeing something from outer space," Lady Deborah MacMillan, who worked as a designer and producer with The Royal Ballet in London, says in the documentary.

"There was the English style, which was extremely polite and refined, and this extremely animalistic person appeared and from then on the bar had been raised," she says.

Nina Loory was a ballerina with Moscow's Bolshoi Ballet from 1963 to 1983. She doesn't agree with Lady Deborah's assessment.

"I don't think he alone changed the role of men in ballet," she tells BBC News. "It started changing in Russia at the beginning of the '30s.

"What he did with the Paris Opera turned them into a top ballet company." But she says his own performances were not always technically perfect and he had a reputation for being "difficult".

Nureyev and Noella Pontois performing in Le Bourgeois Gentilhomme at the Paris Opera in 1979

The film does not ignore the allegations of bullying and even violence against his colleagues.

The 34-year-old African-American dancer Eric Underwood, who was a soloist with The Royal Ballet until 2017, says Nureyev is not a role model for every male dancer.

"His influence is incredibly important, but I couldn't relate to how he looked and moved. Our backgrounds are so different," he says.

The film also focuses on Nureyev's personal and professional relationship with the English prima ballerina Dame Margot Fonteyn, who was 19 years his senior.

There is footage of them in a San Francisco police station, where they are being charged with attending a party where drugs were used. Nureyev observes the proceedings with a mixture of amusement and contempt, while Fonteyn is wearing a grin and a white fur coat.

Nureyev and Dame Margot Fonteyn had one of the most celebrated partnerships in ballet

When Fonteyn was broke and dying of cancer in the early '90s Nureyev paid her medical bills, despite his own health problems.

There is great pathos in the story of the once first couple of dance trying to cheer each other up when he visits her in hospital.

The documentary also details Nureyev's often tumultuous love affair with Denmark's Erik Bruhn, who was one of the world's top male ballet dancers.

"Nureyev eclipsed him and it sort of tore them apart," says David.

Nureyev was to take his final bow as a choreographer in Paris just months before he died

The documentary is being released worldwide, including in some 80 cinemas in Russia, where many of its interviews were recorded.

"They loved him there and wanted to talk about him," Jacqui says.

One of the final scenes shows Nureyev reunited with his friends in post-Soviet Russia, blowing out the candles on his cake on his last birthday in 1992.

Despite everything, Jacqui concludes: "He loved Russia."

Nureyev is now showing in selected cinema.

Follow us on Facebook, external, on Twitter @BBCNewsEnts, external, or on Instagram at bbcnewsents, external. If you have a story suggestion email entertainment.news@bbc.co.uk, external.