Will Gompertz reviews Elmgreen & Dragset's show at the Whitechapel Gallery ★★★★☆

- Published

Marcel Duchamp was a funny guy.

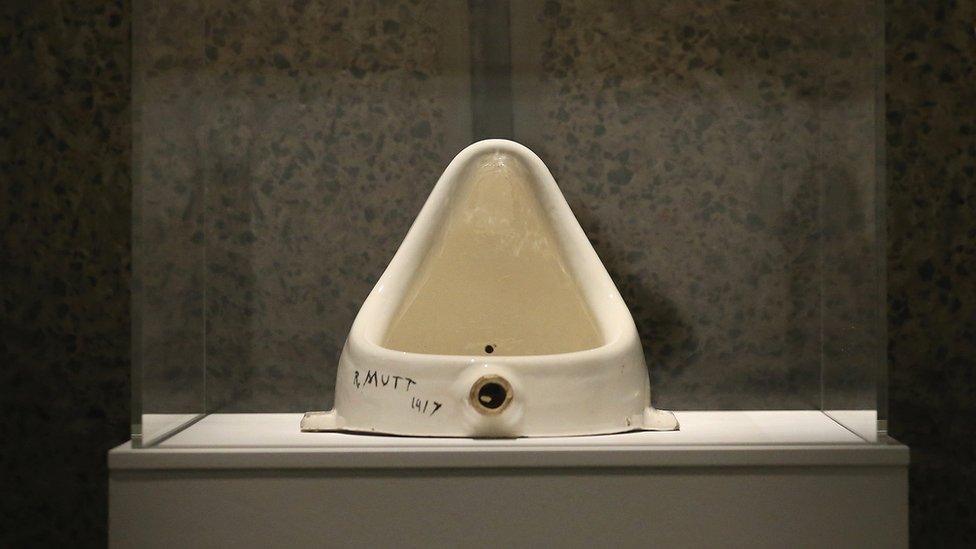

It was he who in 1917 came up with the amusing wheeze to test and tease straight-laced curators by entering a urinal for inclusion in a contemporary art exhibition.

Ever since, artists have been hell bent on trying to outwit and outdo the philosophical Frenchman.

Marcel Duchamp's influential work, Fountain, 1917

And for 101 years they have failed.

There have been some valiant attempts (Robert Rauschenberg's Combines), some famous attempts (Tracey Emin's My Bed), and countless failed attempts (take your pick from those on show at any major modern art museum).

At the better-than-most end of the scale are the Scandinavia double-act Elmgreen & Dragset (Michael Elmgreen and Ingar Dragset), who have been given a mid-career retrospective (the Artworld's version of a minor honour) at the Whitechapel Gallery in east London.

They are the guys who put that fey four-metre high bronze sculpture of a young boy in lederhosen riding a rocking horse on Trafalgar Square's Fourth Plinth in 2012 (Powerless Structures, Fig. 101).

The idea was to gently mock the machismo of the traditional "heroes-on-horses" equestrian statues it faced.

Powerless Structures, Fig.101, by Michael Elmgreen and Ingar Dragset on the Fourth Plinth in Trafalgar Square in 2012

But the capital's then mayor, Boris Johnson, didn't see it that way. He mischievously interpreted it as an emblem to represent Britain's gold medal hopes at the forthcoming London Olympics.

The artists were not amused.

Their serious social commentary had been turned into exactly the sort of jingoistic metaphor they had intended to undermine.

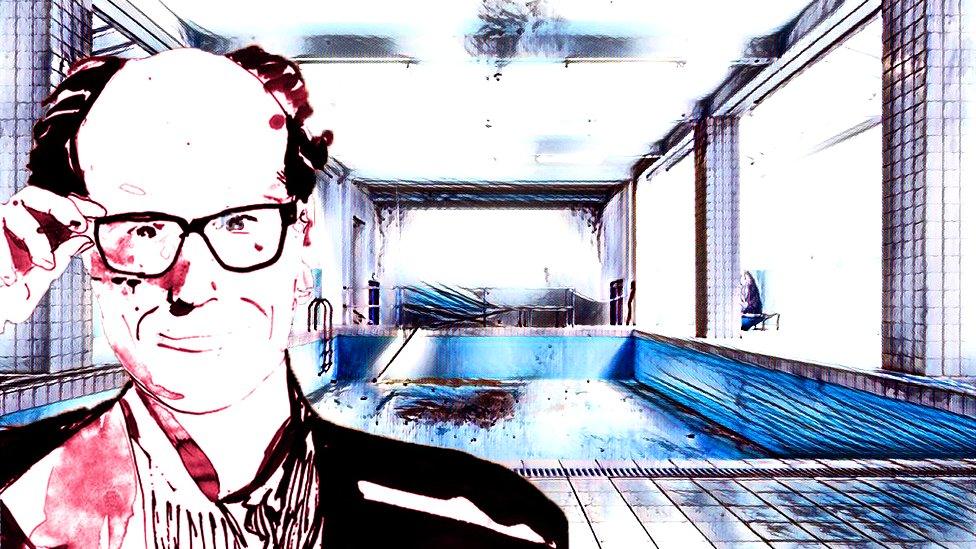

Six years later, the boys are back in town with a riposte to the ex-foreign secretary and his party's austerity policies. It comes in the colossal shape of a derelict, life-sized, municipal swimming pool, which fills the Whitechapel's ground-floor gallery.

Elmgreen and Dragset's The Whitechapel Pool

It is very convincing, right down to the cracked tiles, dusty rubble, and occasional autumnal leaf.

To add to the sense of drama (Ingar Dragset's background is in theatre not art; Michael Elmgreen was a poet), the gallery assistants are dressed as security guards, replete with gaoler's keys and surrounded by little details: a slug climbs a piece of wood, an ice box sits abandoned in a corner; eeriness pervades all.

Little details, such as a slug climbing a piece of wood, are dotted about the pool

On the wall by the entrance door there is a panel on which the backstory of The Whitechapel Pool is told.

It was built in 1901 and paid for "by funds made available by the Borough of Tower Hamlets."

It was renovated in 1953, welcomed 292,000 visitors a-year in "its peak years", and "it is believed that artist David Hockney made his first drawings of the surface of a swimming pool's water at this site".

And then…

"After being abandoned for nearly thirty years, the building was sold to GenTri (geddit?) Investment in 2016, during Boris Johnson's last year as Mayor of London. In January 2019, renowned architecture firm Corner Leviathan (Duchamp loved to play on words, too) will start a comprehensive renovation of the building for the international Desert Flower Art Hotel & Resort."

And there you have it.

A space and a place that was once for the benefit of the general public has been sold off by their bête noir Boris to become a luxury hotel exclusively for the super wealthy.

Of course none of it is true, the story is as fabricated as their swimming pool.

But that's not the point.

The point is the point.

And their point is that civic spaces are being lost to private developers. And so they are.

But not the Whitechapel Gallery thankfully, which was founded in 1901 to "bring great art to the people of east London." It now sees itself as having a "unique role in the capital's cultural landscape and is pivotal to the continued growth of east London as a leading contemporary quarter".

In fact, the increase in civic spaces and buildings in which the public can see art for free has grown massively in the past twenty years, while libraries and other municipal spaces have withered.

You could argue that the likes of the Whitechapel and Tate Modern can precipitate the type of capitalist regeneration that the duo lament; cultural cornerstones that lead to gentrification and rocketing real estate prices.

Michael Elmgreen (left) and Ingar Dragset reveal their new installation The Whitechapel Pool

Next week, both public institutions and Elmgreen & Dragset are likely to be schmoozing the very millionaires and billionaires this work criticises (bankers, developers, hedge-find managers etc) at exclusive private dinners arranged across the capital for what has become known as Frieze Week (a week in early October when the world's wealthiest collectors and galleries arrive en-mass in London for the Frieze contemporary art fair).

Which is why The Whitechapel Pool feels like the right idea in the wrong place.

The art world at this elite level is far too entangled in the world of big business and the super-rich to be a credible voice for social justice.

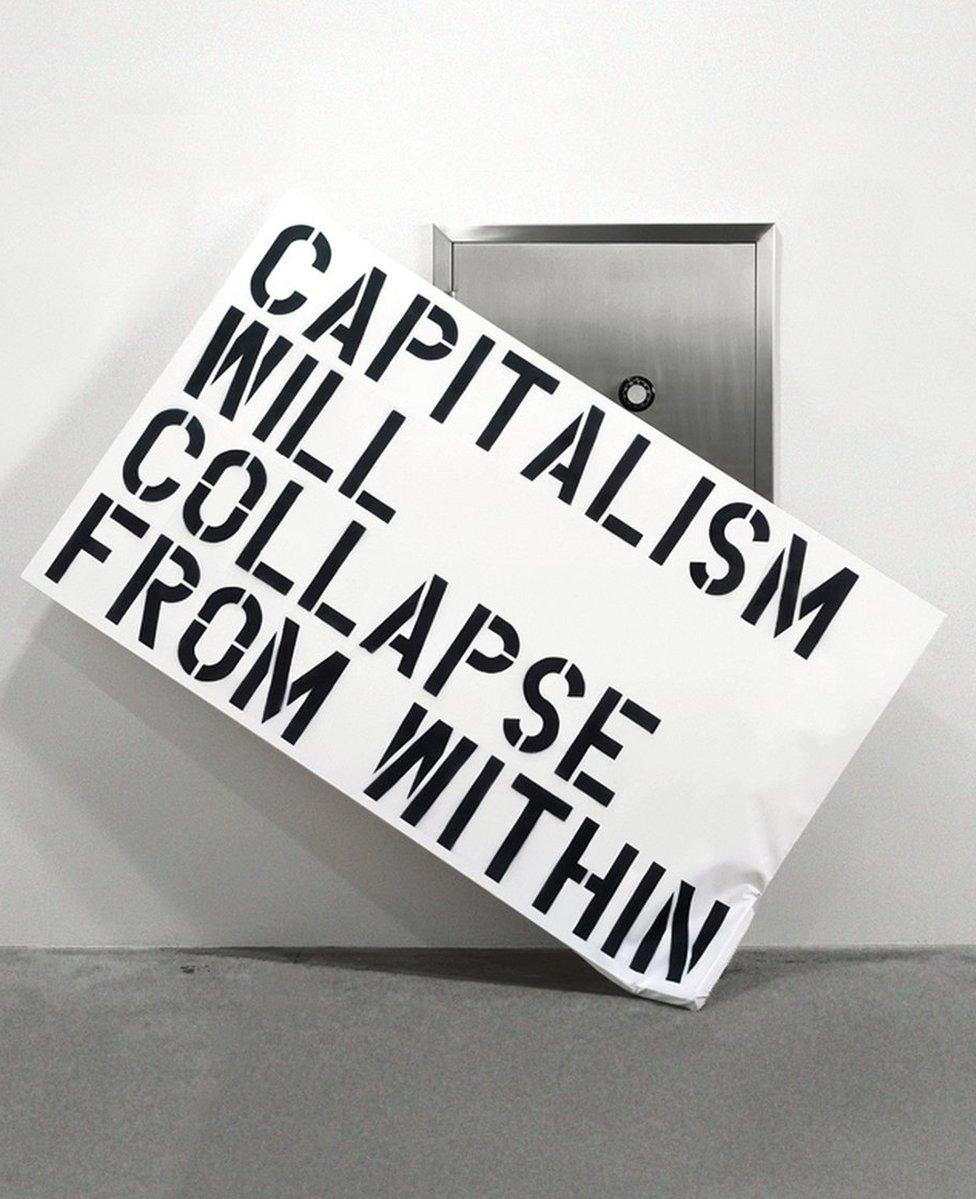

A fact Elmgreen & Dragset acknowledge in a work in the upper galleries called Capitalism Will Collapse From Within (2003).

Capitalism will Collapse From Within, 2003

We see the stencilled proclamation presented in the graphic style of art market darling Christopher Wool: black text on white canvas.

It is hanging off the wall to one side to reveal a safe behind, suggesting that art and money are one-and-the-same: commodities to be stashed away and out of sight at home for personal gain not aesthetic pleasure.

It's not subtle, but then nor is any of their work.

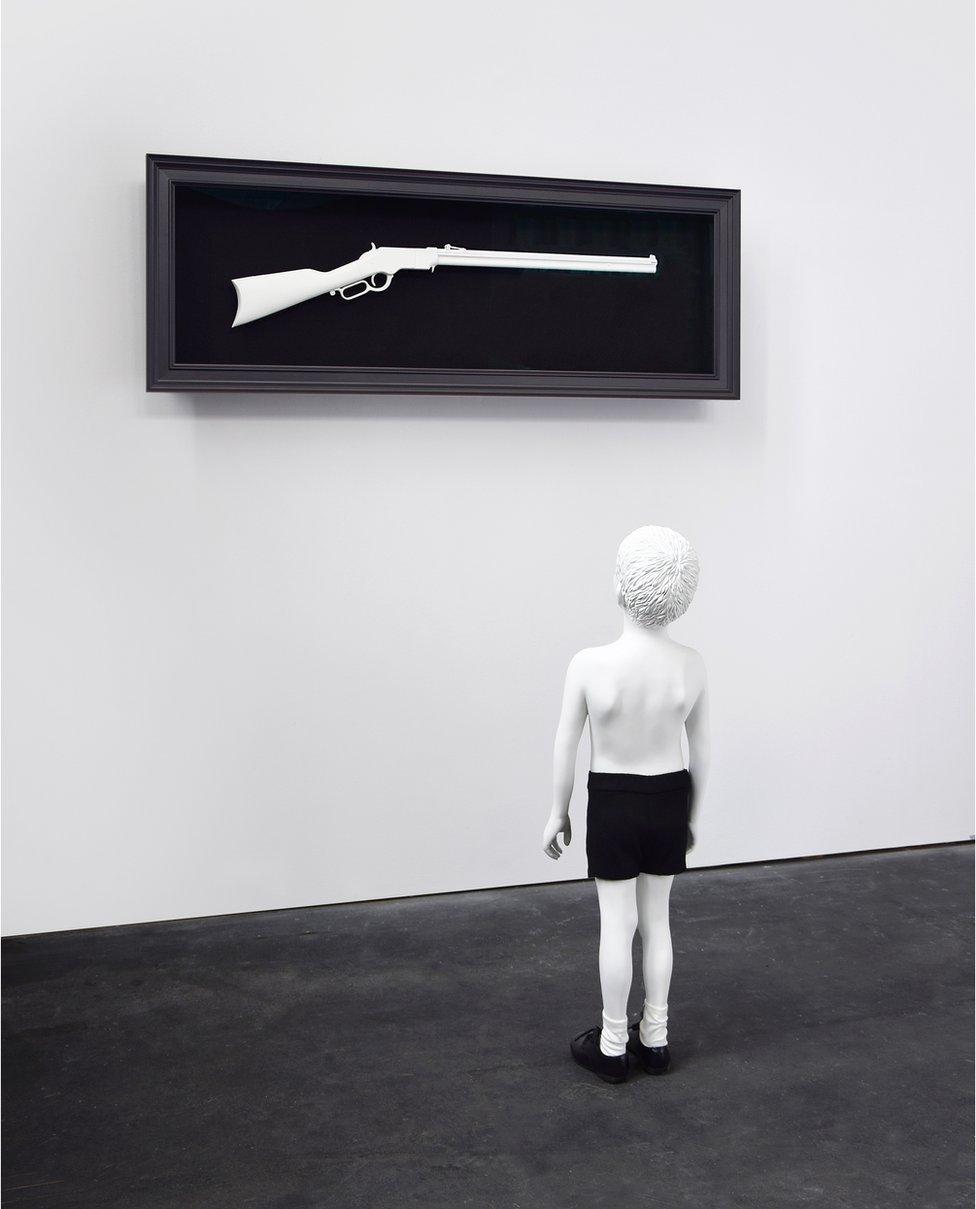

One Day (2015) is a monchrome sculpture in which a boy looks up at a rifle mounted on the wall

One Day (2015), for example, is a monochrome sculpture in which a bare-chested little boy wearing black shorts, white socks, and black shoes looks up innocently at a rifle mounted in a frame on the wall.

Any possible future consequences are incomprehensible to him.

Gay Marriage (2010)

Gay Marriage (2010) consists of two wall-mounted urinals connected by twisted chrome pipes in a lovers' knot, the symbolism of which doesn't need explaining, other than to say it brings us back to Marcel Duchamp.

Who knows what art, if any, he would be making if he were alive today. My guess is it would be darker, funnier, and more original than the work in this show.

But I'm not sure it would make you question the nature of reality quite like Elmgreen & Dragset succeed in doing.

You don't just look at their work, they entice you into their surreal alternative universe, which exists somewhere between The League of Gentleman's Royston Vasey and The Truman Show.

You start to question what you're seeing. Is it a sculpture? Or is it a gallery thermometer? Is it art? What is art? What is real?

They make you think, they make you look, they make you doubt; they make you feel. What more could you possibly want from art?