Tania Bruguera explains Tate Modern's new Turbine Hall installation

- Published

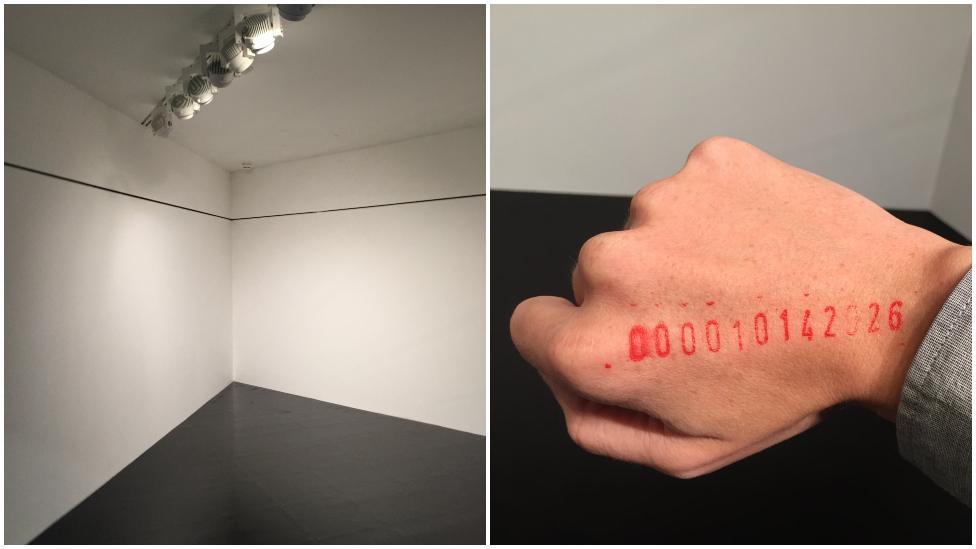

The floor requires body heat in order to reveal the hidden portrait underneath

A new art installation opens today at the Tate Modern. There's just one snag - you can't actually see it.

Walk in to the Turbine Hall and you'll find a plain black floor. The portrait hidden underneath can only be revealed using body heat.

In other words, by getting a very large number people to lie down on it at the same time.

"It's an almost impossible task," laughs Catherine Wood, the museum's senior curator of international art.

"Tania [Bruguera, the artist] chose to put an image under a floor using thermochromic material - heat-sensitive material - because she loved the idea of making a horizontal mural.

"But it's one which is a call to action, because there's no way that you can see this picture unless you join together with many, many other people."

The image which is eventually revealed is a portrait of a young Syrian migrant named Yusef, who fled to the UK from Homs and is now studying medicine.

The theme of migration is one that dominates the whole installation. It's a topic which artists, writers and performers are tackling frequently at the moment.

But where this exhibition differs is that it's actively intended to make you, the viewer, physically uncomfortable.

For one thing, the portrait is accompanied by a "crying room" designed to bring out tears in the viewer (more on that in a sec).

Both come with the constant hum of a bass-heavy, headache-inducing soundtrack, which makes just being in the huge hall an extremely uncomfortable experience.

But, Bruguera argues: "Life is not comfortable. I want people to get out of their comfort zone."

Referring to the giant hidden portrait in the floor, she says says: "The whole idea is we want people to work together, and understand that a lot of things are invisible."

Asked how many bodies it would take to reveal the portrait underfoot, she guesses: "150 maybe? 200?" (We reckon it's significantly more.)

The 50-year-old artist and activist, who was born in Havana, says she was driven not just by the migration crisis itself, but by what she says is the increasingly indifferent reaction to it.

A sign at the exhibition reads: "Journalism and social media bring us 24-hour information on world events. Migration is presented as an ongoing crisis and it often feels like we cannot change what is happening."

The installation, therefore, is intended to "combat the resulting sense of apathy".

But in his two-star review of the installation in The Telegraph, external, Mark Hudson questioned this idea.

"Far worse than the lack of physical impact is the naive and fundamentally patronising rationale behind the whole farrago," he wrote.

"Is apathy really the response of most gallery goers, let alone the British at large, to the phenomenon of migration?

"Wasn't anxiety over migration one of the principal drivers, rightly or wrongly, of the Brexit vote?"

The artist who wants you to cry at her work

In his three-star review for The Guardian, external, Adrian Searle described the installation as "a complicated affair".

"The doomy rumbling bass is perhaps a bulwark against visitors experiencing the latest Turbine Hall project as just another bit of flimsy entertainment. It is a bit unhinging, an intimation of the horrors around us, the horrors ahead.

"Perversely, on a visceral level I like it a lot. But the project as a whole feels somehow unfocused. The overall aim is I think to give us a sense of communality, but instead it feels fragmented."

Away from the floor portrait, the most interesting part of the installation is arguably a small side room off the side of the hall.

This is the crying room.

An organic chemical compound is constantly pumped into the air, which naturally makes your eyes water when you enter.

The sensation is similar to the one you get when chopping onions - where tears often stream from your eyes whether you like it or not.

But the smell here is minty, due to the menthol in the air. The result is similar to the one you'd feel if you chewed a lot of Airwaves, or if you lathered copious amounts of vapour-rub on your chest.

In her four-star review for the i paper, external, Hettie Judah said: "The compound itself is not unpleasant - closer to strong menthol than cayenne pepper - but being subject to a physical response over which you have no control is unsettling."

She added: "A fellow visitor, tear-gassed during political protests, found this sensation anxiety-provoking."

Hudson was also sceptical in his Telegraph review.

He said: "The empathy-inducing vapour made a great nasal decongestant, but did I find myself mentally transported to a leaky boat on the Med? No I didn't."

Part of the experience also involves getting a stamp on your hand with the title of the exhibition - a number referring to a statistic about mass migration which changes constantly.

"It's the number of people who've migrated in the last year around the world, plus the people who have died trying to leave where they're from," Wood explains.

On Monday morning, when BBC News visits, the title of the exhibition is 10,142,926. But it will have already changed by the time you read this.

"The crying room is dealing with the emotional consequences, the emotional fall-out of the migration crisis," Wood explains.

"And it's a sort of antidote to the social media consumption of news and to the tear emoji, to the way people often do this sort of virtue-signalling of tragic content online.

"Tania wanted to created what she called forced empathy."

Follow us on Facebook, external, on Twitter @BBCNewsEnts, external, or on Instagram at bbcnewsents, external. If you have a story suggestion email entertainment.news@bbc.co.uk, external

- Published2 October 2018

- Published2 October 2017

- Published18 September 2018