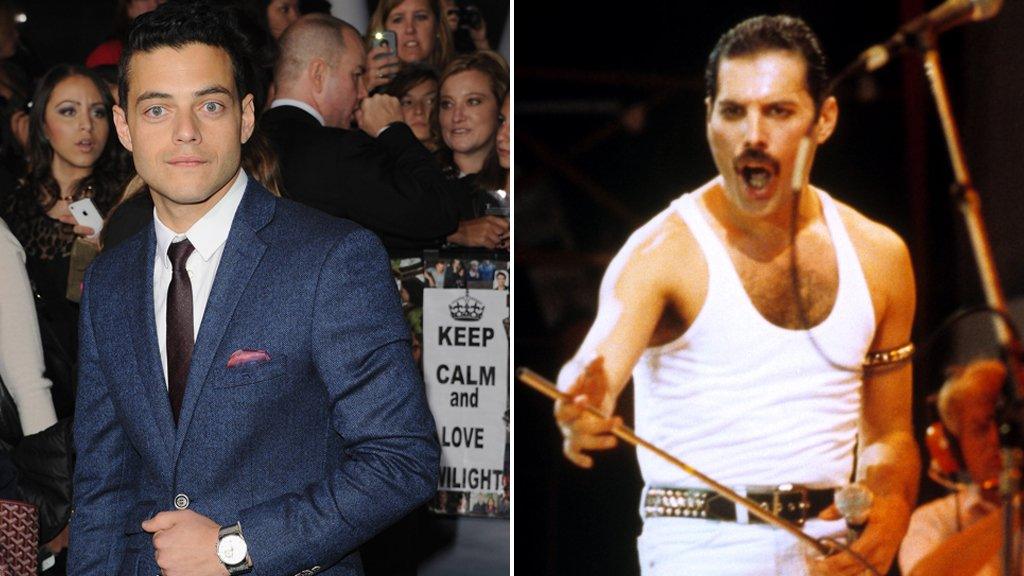

Bohemian Rhapsody: How Rami Malek became Freddie Mercury

- Published

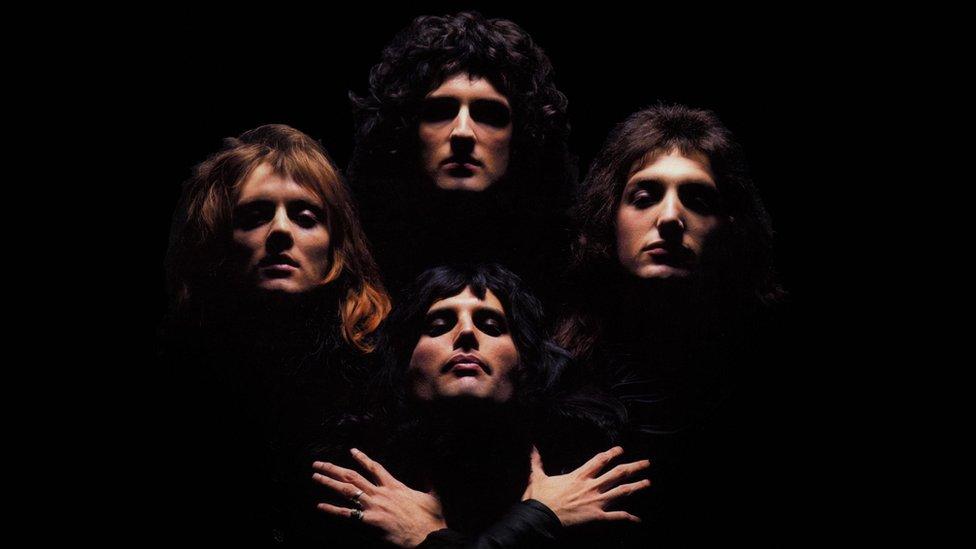

Rami Malek studied hundreds of professional and amateur films of the musician to prepare for the role

Every impersonator will explain how they are always looking to find and exploit a "tell" - a little catchphrase or physical tic a famous person had that helps a person imitating them to slip into character.

To become De Niro, it's "You talking to me?". For Adele, it's THAT cackling laugh.

And for Rami Malek, becoming Freddie Mercury was as easy as going, "Awlright".

That gave him the star's effete British accent and, more importantly, told everyone on the set of the Mercury biopic Bohemian Rhapsody that he was ready for action.

"Everyone on set would hear me going 'Awlright' and that meant 'hurry up and move it along, let's rock and roll'."

But Malek's portrayal of Queen's frontman goes beyond an impersonation.

He has the preening, peacock strut of the star's stage persona down to a tee. So much so that, watching the film's breathtaking recreation of Queen's Live Aid set, it's easy to forget you're not watching the real thing.

He also excavates the star's psyche to reveal a vulnerable, anxious soul - who disowns his birth name, Farrokh Bulsara, but whose alter-ego only comes alive in the spotlight.

"There's just something quite unsettled about him," says Malek.

"He has such a compassionate side, and he longs for the sense of community and love and companionship… but there's a sense of distance there, somehow."

The film recreates the Live Aid concert in 1985

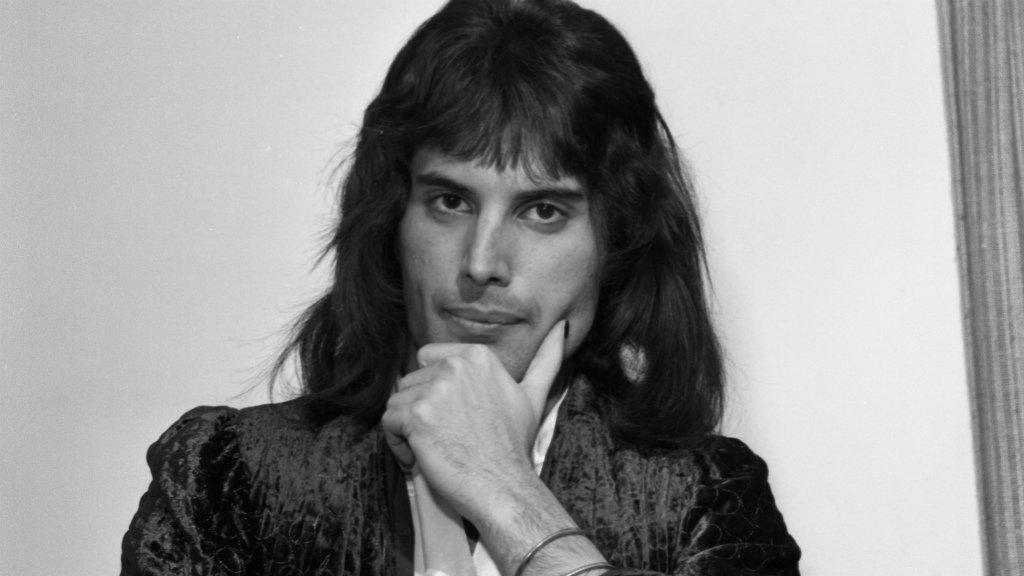

It was hard to uncover the real Mercury, though. He was famously waspish in interviews, which he viewed as a chore, describing himself as "a dandy" and "a musical prostitute" instead of revealing anything too intimate.

Because of his untimely death of Aids-related pneumonia in 1991, there are no memoirs to give a glimpse of his innermost thoughts.

"I kept searching for ways into the man and then I realised, he left us a diary and it's in all of the songs," says Malek.

Two of the most revealing were Lily Of The Valley and You Take My Breath Away - both of which are quieter and more contemplative than the bullet-proof confidence of Don't Stop Me Now or Another One Bites The Dust.

"Trust me, I pushed for those songs to be in the movie, because they informed so much of Freddie to me," he says. "But no-one's singing those ones at karaoke."

Indeed, the film has been accused of obscuring "the real Freddie". It glosses over his excesses - the sex, the drugs, the parties with naked waiters and dwarves carrying trays of cocaine on their heads.

Others fretted the story would be "straight-washed" - but despite focusing on his common-law wife, Mary Austin, Mercury's closeted bisexuality is a key part of the film's script.

"It's not a documentary," stresses Malek, "and we take liberties with the chronology because we have two hours to tell the story.

Freddie Mercury was born in Zanzibar but raised in Feltham, West London

"It was tricky at some points. We thought, 'Are we going to show him in Zanzibar as a child? Will we show him in St Peter's boarding school?' And those are things that we shot but we realised we have a finite amount of time.

"So we chose to focus on this period from the early 70s to 1985. The agenda was to celebrate this human being."

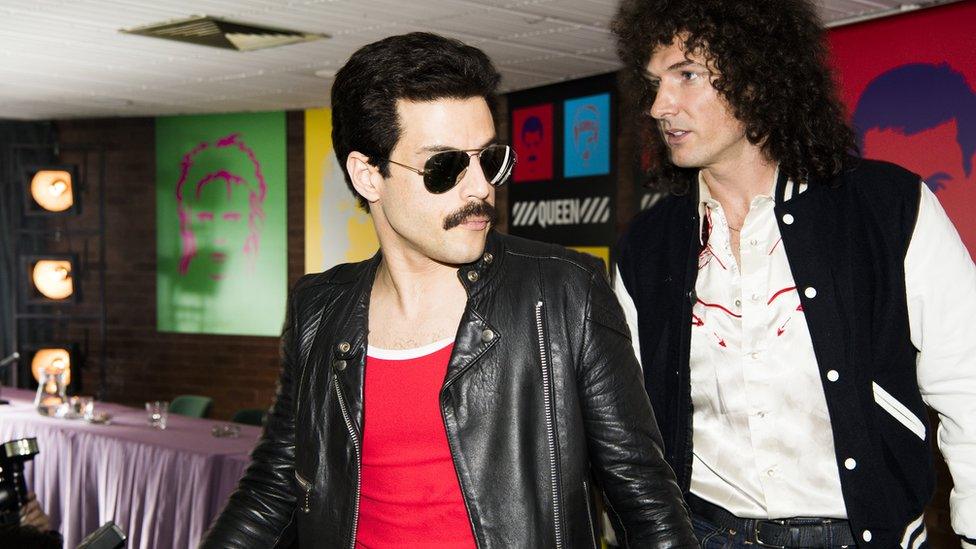

No-one can question Malek's commitment to the role. He auditioned for six hours, long before the film was financed; and spent hours studying shaky, fan-shot Queen videos to pick up Mercury's mannerisms and stage patter.

During development, he'd fly to London for singing and piano lessons, working with a dialect coach and choreographer Polly Bennett, who encouraged him to watch Mercury's inspirations - Jimi Hendrix, David Bowie and, especially, Liza Minelli in Cabaret.

Malek also had to get himself some new teeth…

As the film explains, Mercury was born with four extra incisors, which pushed his upper teeth into an extreme overbite but also, he believed, gave his voice extra resonance.

The actor got his false teeth made months in advance of the film shoot, wearing them between takes on his TV series Mr Robot to make sure he didn't lisp or slur on the set of Bohemian Rhapsody.

Production troubles

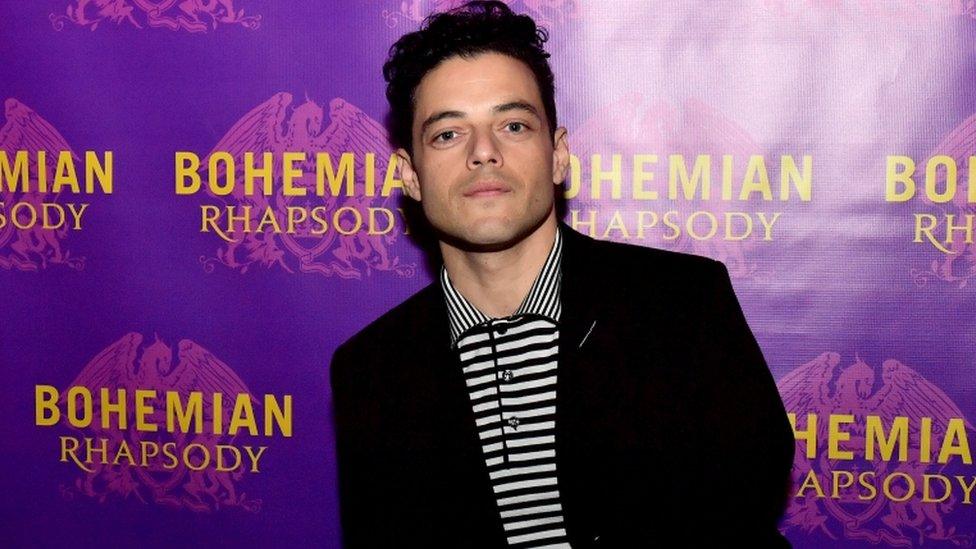

All the hard work paid off. Early reviews are split on the movie's quality (Kyle Buchanan of The New York Times called it a "glorified Wikipedia entry, external") but everyone is agreed on Malek's "outstanding" performance.

"If the idea was to firmly plant Rami Malek among top contenders for the best actor Oscar," wrote Deadline's Pete Hammond, external, "then it was mission accomplished".

That's pretty remarkable, given the film's troubled gestation.

By the time Malek signed on, it had already burned through three lead actors, several scripts and two A-list directors. Then, with 16 days of filming left to complete, director Bryan Singer was fired for erratic behaviour after failing to turn up on set.

Dexter Fletcher was brought in to complete the project, amid rumours that Singer and Malek had butted heads.

The actor has admitted there were "creative differences" on set but shrugs off the change of director as a mere bump in the road.

The standard (and presumably studio-approved) explanation, repeated in a multitude of interviews, is that he was used to having multiple directors on Mr Robot, and this situation was no different.

"It's not odd for me," he told Collider, external. "It's not debilitating to have a fresh voice in there, especially on the last legs, when everybody gets tired."

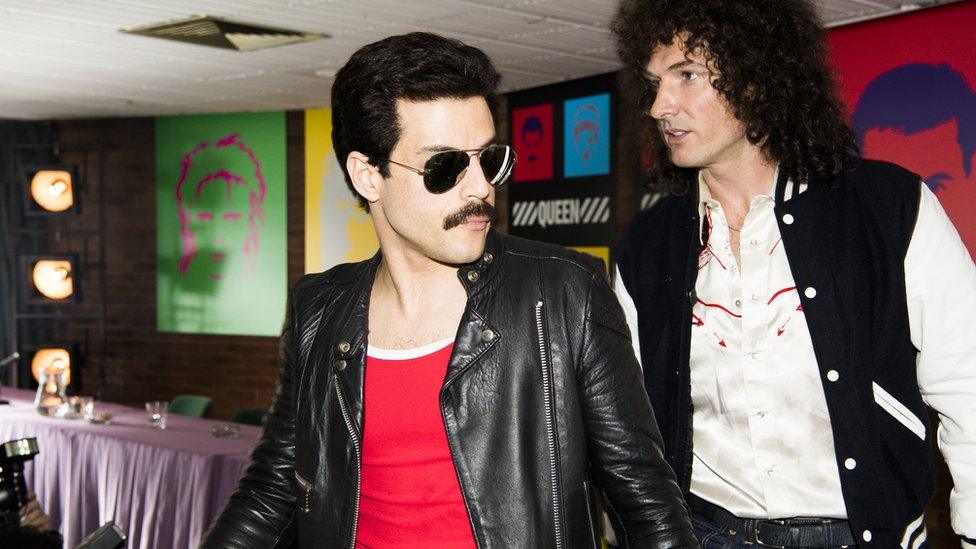

Rami Malek and Gwilym Lee go back to the 80s

But if the film's pre-publicity focused on its troubled gestation; the reveal of the first trailer left everyone talking about Malek's stellar transformation.

What, I wonder, was the part of Mercury he couldn't leave behind when the cameras stopped rolling?

"I think just his spirit," he says. "This refusal to be stereotyped, this refusal to conform.

"He's a revolutionary, I think, because I don't think he ever allowed himself to be marginalised or segregated into one particular group.

"He essentially did what we as a collective society are all aspiring to do at the very moment - which is to not be labelled, to be as authentic as we possibly can without anybody trying to put us in a particular box.

"He was chastised for it at the time, but you look at it now and realise he was trailblazing. He was saying, 'I am going to be me, and if you don't like it, you can get stuffed.'"

Follow us on Facebook, external, on Twitter @BBCNewsEnts, external, or on Instagram at bbcnewsents, external. If you have a story suggestion email entertainment.news@bbc.co.uk, external.

- Published29 October 2015

- Published15 May 2018

- Published6 September 2017