Will Gompertz reviews Russia, Royalty & the Romanovs ★★★★☆

- Published

This exhibition at The Queen's Gallery in Buckingham Palace starts with a huge painting of a huge man: the aptly-named Peter the Great of Russia, the first Tsar to leave his country in over 100 years.

The catalogue says it presents us with "a tall, virile, handsome warrior".

Sir Godfrey Kneller's portrait of Tsar Peter I (1672-1725), who was the first Russian ruler to visit England

The diplomat Prince Boris Kurakin (1676-1727) was similarly enamoured with the artwork. He said: "The famed portrait of His Czarish Majesty standing in all his imperial armour and so attractive, that I have nowhere seen its equal."

I do not share their view.

Godfrey Kneller's very grand and historically significant picture depicts a bug-eyed, 6ft 7in, fey-looking 26-year-old who seems to be as much at home in his suit of armour as Ann Widdecombe was on Strictly Come Dancing.

The painting was Peter's gift to the English king, William III, to mark his three-month-long fact-finding visit to England in 1698. The ambitious young ruler was keen to build a Russian navy from scratch to match those of the great European powers.

William III was happy to overlook Peter the Great's wayward behaviour

So he rented a house in Deptford from the writer and diarist John Evelyn, a chum of Samuel Pepys, and set about learning all there was to know about shipbuilding at the local dockyard, while hoovering up tips on navigation from the nearby Royal Observatory at Greenwich.

The trip was a tremendous success for Peter, who, by the end of his reign, had 28,000 men serving 49 ships and around 800 smaller boats.

It wasn't so good for John Evelyn, though. His majestic tenant had a rock star's approach to renting: paintings were used for target practice, wheelbarrows as go-karts, and the furniture - that which remained - was left in more pieces than a jigsaw of St Petersburg.

William III was happy to overlook the wayward behaviour of his Russian opposite number, seeing the empire-building emperor as an important strategic ally and valued trading partner. And so began a diplomatic relationship between the two monarchies that would span centuries, marriages, wars and the exchanges of many gifts and paintings.

The coronation portrait of Empress Catherine II (1729-1796), by Vigilius Eriksen, was believed to have been given to King George III

On the whole, it is the gifts and subsequent purchases of Russian objects made by the British Royal Family that are the stars of this show.

The paintings are a mixed bag - some good, some bad, none great. Quite unlike the cabinets full of pieces by the Russian jeweller Peter Carl Fabergé, which are exquisite.

His pair of late 19th Century decanters topped off with silver dolphins with mouths formed into spouts are wonderful. As is the gold and blue moire guilloche enamel cigarette case, which is decorated with a diamond-set snake biting its tail, a symbol of everlasting love (it was given to King Edward VII by his mistress, Alice Keppel).

And then there are the three Imperial Fabergé Eggs, the most striking of which is the Mosaic Egg and Surprise. The lattice-like exterior is not only the most beautiful piece of craftsmanship, but is also a profoundly sad vessel encapsulating a tragic event.

Inside the egg, the "surprise" is an enamel portrait of five children in profile, on the reverse of which is a basket of flowers and an inscription of each of their names. Tsar Nicholas II commissioned it for his wife Alexandra - Queen Victoria's granddaughter - as an Easter present. The children it depicts are theirs.

Mosaic Egg and Surprise (1914) by Fabergé, was originally commissioned by Nicholas II, and later bought by King George V and Queen Mary

It was made in the spring of 1914 shortly before Russia became embroiled in World War One. Nicholas was not a great leader, nor a popular figure. Millions of Russian soldiers died, leading to revolution and his forced abdication in 1917. The provisional government confiscated the Mosaic Egg and Surprise.

The Tsar asked the British Royal Family to rescue him - after all, the families went a long way back, as this exhibition demonstrates.

King George V declined.

On 17 July 1918, Tsar Nicholas, his wife and all five children were executed by Bolshevik guards.

Fifteen years later, George V purchased the Mosaic Egg and Surprise from Cameo Corner, London, for £250.

This is but one of the hundreds of historical events reflected in the objects and paintings in this rigorously researched exhibition.

It is a grand tale of international relations and inter-family arrangements, of cultural exchange and competing agendas. The major players line the walls in over-the-top gilt frames, while the objects that fill the exhibition spaces tell their stories.

Laurits Regner Tuxen's painting of the Marriage of Nicholas II, Emperor of Russia, in 1894, to Princess Alix of Hesse, who was Queen Victoria's granddaughter

There are instances when the object is not as interesting as the piece of history it represents, but that is not the case in the sideshow of Roger Fenton photographs of the Crimean War that is connected to the main exhibition, which serves as a reminder that all was not always rosy in the 300-year Anglo-Russian relationship.

Fenton's intelligently composed images of the soldiers and battlegrounds are as good as those produced on any subject since the birth of the medium. When you take into account the limitations of his equipment and the hostile environment in which he was using it, you quickly recognise that his photographs are remarkable.

Having been commissioned by the print publishers Thomas Agnew & Sons to take pictures of British and French soldiers as source material for a studio painting by Thomas Barker, Fenton set off for the Crimea in the spring of 1855 with a makeshift, horse-drawn photographic van and an assistant.

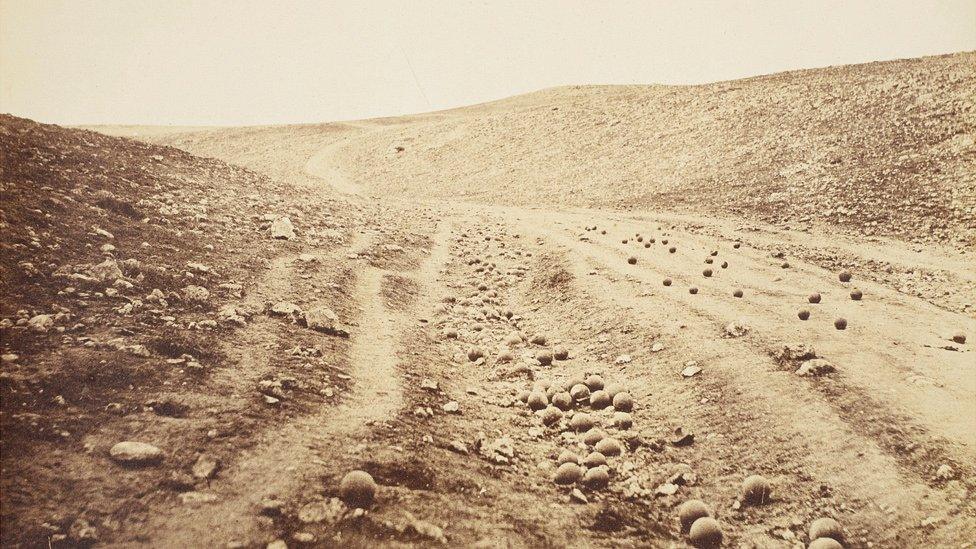

He organised group photographs, individual portraits and desolate landscapes strewn with the debris of war. The most famous photo is Valley of the Shadow of Death - a bleak and barren dirt track littered with cannonballs: an image of Armageddon.

Valley of the Shadow of Death, 1855 by Roger Fenton, who places the viewer at the bottom of the ravine filled with cannonballs

It is a haunting picture of war without any blood or bodies.

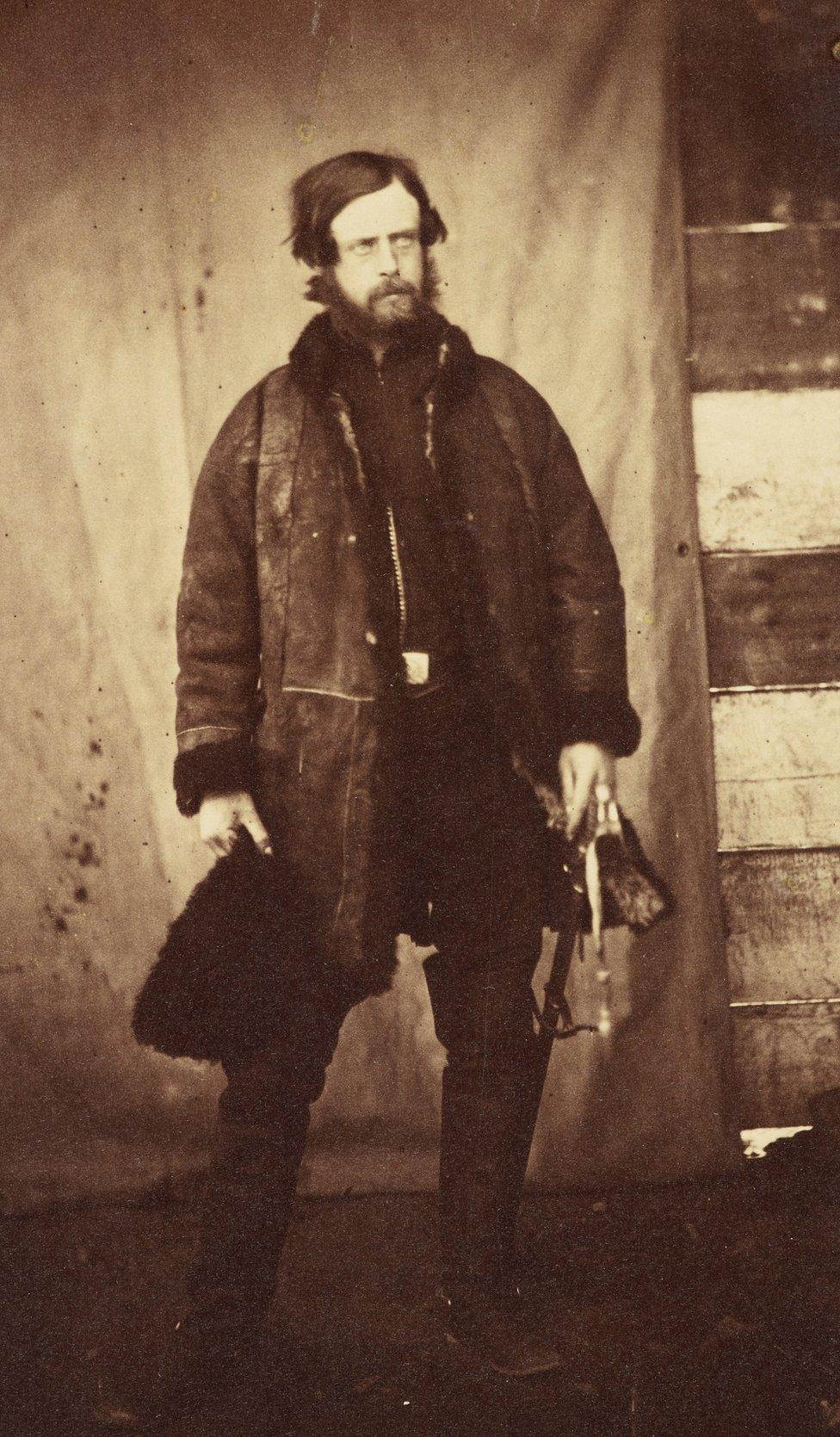

His portrait of the unlucky Lord Balgonie, who stares out into the middle distance in wide-eyed confusion, is thought to be the first image taken of shellshock.

Roger Fenton's photograph of Lord Balgonie in 1855, is thought to be the first visual record of someone suffering from "shell shock"

There are few occasions in the exhibition where a Fenton photograph is hung beside a picture an artist has produced from it - and the comparison is illuminating. It brings home Fenton's genius for finding the truth in his subject, and the utter hopelessness of the artist attempting to do the same.

When he returned home, his Crimea photographs were much admired by Queen Victoria and her tech-savvy husband Prince Albert, who had previously commissioned the photographer to take portraits of the Royal Family.

Queen Victoria and Prince Albert, 1854, by Roger Fenton

Being sensible people, they bought the lot.