How WWI shaped the nature of filmed news

- Published

A lot of Peter Jackson's film comes from the material of the groundbreaking documentary The Battle of the Somme

For Remembrance Sunday BBC Two is screening Peter Jackson's World War one documentary They Shall Not Grow Old - an extraordinary reworking of newsreel archive from the western front, much of it colourised to show soldiers as though filmed only yesterday. But a century ago how did the early newsreels cover life and death in the trenches? And were they showing the real thing?

Only the keenest silent film buffs know much about cameramen Geoffrey Malins and J B McDowell. But hundreds of millions of us know their work on screen - and many more are seeing it now thanks to They Shall Not Grow Old.

Virtually all British footage from World War I trenches and battlefields was filmed for the government-controlled organisation British Topical. Malins and McDowell shot the great majority of it and their work has featured in countless documentaries in the decades since.

Dr Lawrence Napper has studied the way newsreel coverage changed during the war.

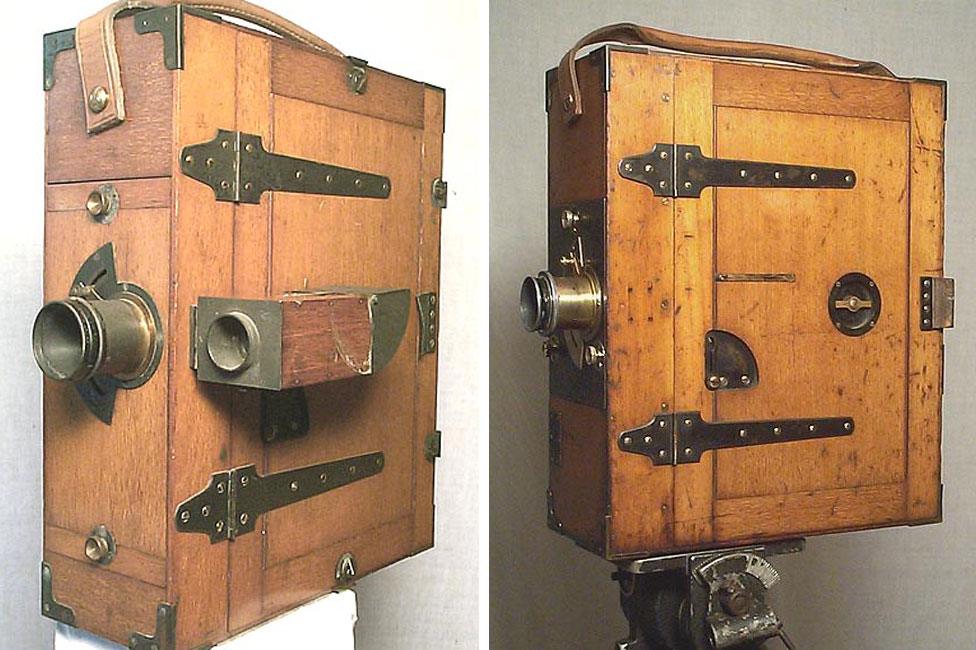

The kind of ancient Moy and Bastie camera which the newsreel cameramen used in World War 1

"War broke out in July 1914 but it wasn't until almost the end of 1915 that British news cameramen were allowed to France," he says. "Partly it was that film had been seen as entertainment for the working class - no-one in Whitehall knew what to make of endless requests from companies like Pathe for access to the trenches. Newsreels were a pretty new medium and pre-war they'd dealt only with soft stories - the Boat Race or a royal visit somewhere."

The big turning point came with a documentary called The Battle of the Somme, which lasts around 70 minutes. It used Malins' and McDowell's material and it was a massive hit. "It's been claimed a greater proportion of the British population saw it than any other film ever," Napper says. "There was a real hunger to see how the war was going."

Stephen Badsey of the University of Wolverhampton has been studying World War I footage for much of his career.

"One of the reasons newsreel cameraman were finally allowed out to France was because it became clear Britain could no longer rely on a volunteer army. Conscription was coming and the government needed Britons to see what was being done in their name."

Badsey says there are around 1,000 different items of film, ranging from very short clips to complete stories. "Inevitably there are some sequences which get used again and again - quite a lot of Peter Jackson's film comes from The Battle of the Somme.

'The real thing'

"There's some extraordinary material in the original documentary which impresses even now. You could say it's the first combat documentary ever shot.

"But public taste changed quickly. By the summer of 1917 Britain was getting a bit bored with documentaries and the War Office in effect bought out the Topical Budget company and issued short twice-weekly newsreels. The Whitehall propaganda machine was in control."

Ignoring political machinations at home, Malins and McDowell had continued to operate as best they could on the Western Front. They were using big hand-cranked Moy and Bastie cine-cameras which were normally secured to a heavy tripod and couldn't be moved easily.

"In Peter Jackson's film there's a poignant scene of men waiting to go into battle," says Dr Lawrence Napper

All of which raises the question - how much of what we see of British Topical's work (which means most of what we ever see from the trenches) is genuine? And how much of the action was staged and a century later needs to be treated with care?

Napper thinks the answer is complex.

"In Peter Jackson's film there's a poignant scene of men waiting to go into battle, which is taken from The Battle of the Somme. We know it's the real thing, partly because we know exactly where Geoffrey Malins filmed and when.

"And we're very familiar with scenes of artillery shooting towards the German lines - but that would be a long way from any real Germans because that's how artillery works. So usually you'd assume those sequences are real. But people sometimes think they've seen big battle sequences close up, which in reality barely exist.

British troops on night raid in World War I

"Non-staged material of things exploding was almost always shot low-down with Malins poking his camera briefly above the top of the trench. Any explosions would in reality have been in the distance.

"Reviews have mentioned Peter Jackson's achievement in colourising the material. What has been spotted less is that he's scanned and digitally zoomed in so certain explosions seem far closer than they really were: they look as though they were shot on modern Steadicam. They're real explosions but originally they were smaller in frame and across no man's land."

Napper says the work of Malins and McDowell remained influential even after the war. "In the 1920s you get reconstructions of battles but filmed in peacetime. People were trying to recreate what the two men might have filmed if they could have done so without getting shot."

One thing about their work which is genuine often surprises people - the inclusion of dead bodies. Napper says it was controversial even at the time.

"When the Somme film was shown in 1916 the Dean of Durham was among those who protested at the depiction of death. But there were others who wanted to see the reality of war." It's a debate that goes on a century later.

They Shall Not Grow Old is on BBC Two on Sunday 11 November at 21.30 GMT.