Talking horses and perfect faces: The rise of virtual celebrities

- Published

Virtual YouTubers are animated characters, often anonymously controlled by human users

A different kind of internet celebrity is emerging; virtual characters that talk on YouTube or pose on Instagram like living, breathing people. Is this the dawn of a new breed of star?

Kizuna AI has 2.3 million YouTube followers. She posts videos nearly every day, talking to camera about life, love and video games.

But she is also a CGI construct; a fictional character made to look like a young woman, voiced by an actor, claiming to be an advanced artificial intelligence.

Her channel is part of a growing trend in Japan for so-called virtual YouTubers, or VTubers.

Much like regular YouTubers, these personalities speak about everyday subjects - from relationships to TV shows - but under the guise of an animated avatar, created using inexpensive motion-sensing technology.

This type of virtual personality is growing in popularity. Earlier this year, the Tokyo-based data research firm User Local Inc reported that the number of VTubers had exceeded 4,000, external; more than doubling over the course of two and a half months. And it's not only people in Japan that are interested in this subculture.

"It's a trend that's gained a lot of attention in the past year," says Minoru Hirota, who runs the Japanese virtual reality news website, Panora.

"Kizuna AI has gained popularity in Europe and the United States, as well as Thailand and South Korea. It's said that over half of the subscribers to the YouTube channel come from overseas."

Kizuna AI has more than 2 million followers on YouTube

Since Kizuna AI started making videos in 2016, a wave of popular VTubers have emerged. These include the cat-eared Kaguya Luna, external, Baacharu , external- who appears as a suited horse - and Nekomasu, external; "a cute girl who has fox ears, but the voice of a man who works part-time at a convenience store," explains Hirota.

One London-based VTuber, Ami Yamato, external, appears as a CGI character in the midst of "real" locations, often being shown beside flesh-and-blood humans in her videos.

This overlap between the real and virtual is a common theme. In August this year, the Japanese record label Sacra Music hosted , externala "concert" for Kaguya Luna, bringing together 200 spectators. Instead of a physical venue, the event took place in a shared digital world. Each audience member sat at home using a virtual reality headset, but appeared in the "concert" as a brown blob wielding a pair of glow sticks. Collectively, the crowd of avatars watched the avatar of Kaguya Luna perform on stage.

Manufactured celebrity

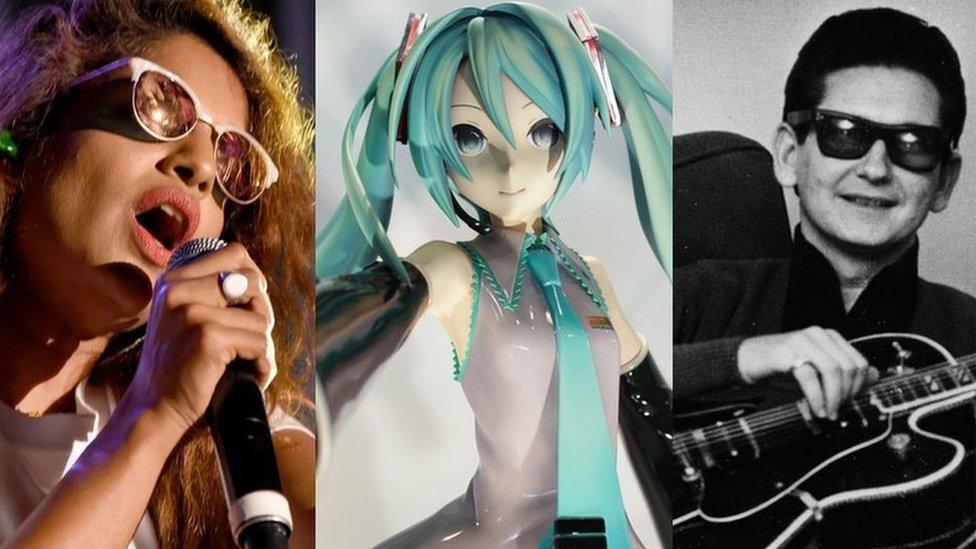

VTubers like Kaguya Luna and Kizuna AI aren't without precedent. In 2007, the Japanese media company Crypton Future decided it wanted a relatable character to be an image for its voice synthesiser software. The result was Hatsune Miku, external, a 16-year-old with turquoise pigtails that would go on to appear in various manga, anime and video games, and eventually appear "live" in concert as a hologram.

In the West, at the same time as VTubers are emerging in Japan, virtual personalities have infiltrated Instagram. Lil Miquela, for example, has built up 1.5 million followers with candid CGI selfies. Much like Ami Yamato, she will often appear beside actual people in real places. Claiming to be a Brazilian-American 19-year-old model, Lil Miquela has even had relationships and feuds with other CGI Instagrammers - all of which are connected to an LA-based company with backing by major venture capital firms, external.

Another virtual Instagram star is Shudu Gram, external, who caused a great deal of confusion when she first appeared on the scene in 2017 with highly stylised images featuring a golden iindzila; neck rings sometimes worn by the Ndebele people of South Africa. The pictures were staged and lit like fashion photography, even though they had actually been created using a 3D software programme.

Allow Instagram content?

This article contains content provided by Instagram. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read Meta’s Instagram cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

"Fashion is so retouched and filtered, that our expectation of what a fashion photograph looks like is completely different from our expectation of what a person on the street looks like," Cameron-James Wilson, the photographer who created Shudu Gram, tells me. "We have this idea that supermodels are perfect anyway, so a 3D supermodel doesn't stand out that much."

Unlike Lil Miquela, any illusion of Shudu as an autonomous CGI character was shattered when Wilson stepped forward as the creator. As a white man from the UK who had created a black, female virtual Instagram star, Cameron was criticised for projecting a fantasy of black womanhood, external, and for profiting from images of blackness without having to pay a black model.

He acknowledges the criticism but says he has made it a point to be transparent about his role in the project.

Shudu is among the digitally-created 3D models used in fashion brand Balmain's latest campaign

"As an artist you do want to provoke thought and inspire debate. I do talks and interviews as myself; putting myself out there. I like to know that when people support what I do they are supporting me as a person."

Behind the mask

In the world of virtual personalities, anonymity can be a powerful force. What would the reaction to Shudu Gram be if the identity of its creator remained a secret? Would Kizuna AI be as popular as she is if the account wasn't built on the fantasy of an autonomous artificial intelligence?

One subculture within this subculture, which Hirota calls "Virtual-Bishoujyo-Juniku", or "virtual beautiful girl incarnation", is based around male illustrators drawing female characters that they then inhabit using a voice changer. The internet has long made it easy of people to present themselves as different genders, although Hirota compares this to an even older tradition in Japanese Kabuki theatre, called Onnagata, where male actors play female roles.

In Japanese Kabuki theatre, an onnagata is a male actor who plays a woman's role

Dr Griseldis Kirsch, lecturer in contemporary Japanese culture at SOAS, thinks anonymity could also play another, more political, role for VTubers in Japan.

"Japan has very strict internet laws, and very strict broadcasting laws," she says.

"If you use motion capture to turn yourself into an animated character, you can be critical, cheeky; you can bypass censorship."

In 2017, the UN's special rapporteur on freedom of expression, external reported "significant worrying signals" about Japan's approach to freedom of expression. The investigation claimed that a law permitting the government to suspend broadcast licences for TV and radio outlets for spreading misinformation was being misused, putting pressure on those organisations not to cover sensitive political stories.

Gaze across VTuber feeds and you won't find much in the way of political debate, but the mask of an avatar nevertheless allows VTubers to talk to an audience without showing their face.

According to Hirota, that is a core reason many people create CGI avatars in the first place: "There are many people who resist appearing on the internet in Japan. Being a VTuber helps those people."

A lucrative subculture

Ultimately, though, the driving reason for the rise of virtual internet celebrities is likely to be money. Dr Kirsch mentions the "Otaku" culture of anime and manga enthusiasts in Japan, and how VTubers - with their, mainly female, anime avatars - overlap with this scene.

"It's a lucrative subculture, and brands spend money on it deliberately. These virtual YouTubers are riding the same wave."

Several VTubers, including Kizuna AI, are popular characters for cosplayers

Much like regular YouTubers or Instagram influencers, the likes of Kizuna AI and Lil Miquela attract attention from high-profile companies, who will pay to have their products featured. Indeed, using a controllable CGI avatar rather than a human model for this purpose could have its advantages.

"I definitely think the character-driven nature of advertising helps elevate the VTubers in Japan to something more enticing than a regular person, as they're much easier to market and project on to," says Lauren Hunter, a cosplay (dressing up) and anime enthusiast.

This sentiment is echoed by Wilson, who says he can envision a time when fashion brands have their own CGI characters, akin to Crypton Future's Hatsune Miku, each with their own social media channels; a mascot or model.

"Otherwise, they could put work into raising a model's profile, only for them to leave for a competitor brand several months later when their contract is up. With this kind of technology, they could develop a character in parallel to using real life models."

At a time when facial recognition technology is becoming ever more accessible, it has never been so easy to inhabit a fiction. Whether virtual YouTubers and Instagrammers become part of the internet's make-up, or fade as a short-lived fashion, for now the lines around reality continue to blur.

Follow us on Facebook, external, on Twitter @BBCNewsEnts, external, or on Instagram at bbcnewsents, external. If you have a story suggestion email entertainment.news@bbc.co.uk, external,

- Published3 December 2018

- Published3 October 2018

- Published27 October 2018

- Published29 December 2017