Will Gompertz on Mary Poppins Returns starring Emily Blunt and Lin-Manuel Miranda ★★☆☆☆

- Published

Back in the 1990s a film studio undertook some very expensive research in an attempt to discover if there was a formula, based on empirical data, for making commercially successful movies.

To the executives' delight, the research company reported back that it had indeed identified the way to make money. A meeting was hastily arranged.

"We've spent millions on this research," said the suits. "What's the magic formula?" The researchers explained that no movie could ever be absolutely guaranteed a box office hit, but they had narrowed down the odds of failure to significantly minimise the risk of financial catastrophe.

The suits look at each other excitedly. This was going to be a breakthrough moment in the movie business.

What would the answer be?

Horror pictures?

Rom-coms?

Sci-fi, maybe?

"No," the researchers said. "The money-spinning film genre is…sequels!"

I re-tell this old (apocryphal?) story because it is pertinent to Mary Poppins Returns in two ways. Firstly the film is a sequel and therefore enjoys what everybody already knew before the research consultants' "revelation," which is audience recognition and appreciation gives a film a crucial leg-up at the box office.

And secondly, it reveals the ultimate truth of trying to apply business logic to a creative endeavour.

You can't.

Everything about Mary Poppins Returns suggests it should be a great movie. Disney has made it with genuine affection and sensitivity towards its original. It has an excellent cast including Ben Whishaw, Julie Walters, Lin-Manuel Miranda, Meryl Streep, and Emily Blunt - always a mesmerising screen presence - as Mary Poppins.

Jane (Emily Mortimer), John (Nathanael Saleh), Annabel (Pixie Davies), Ellen (Julie Walters), Jack (Lin-Manuel Miranda), Georgie (Joel Dawson) and Mary Poppins (Emily Blunt)

It looks fantastic, the special effects are special, and a great deal of money has clearly been spent in the hope of making it supercalifragilisticexpialidocious.

All of which is great. Except the movie - unlike the eponymous super nanny - never quite takes off.

For all its good intentions Mary Poppins Returns lacks the inherent charm of the 1964 classic starring Julie Andrews.

Julie Andrews immortalised the role of Mary Poppins in the 1964 musical

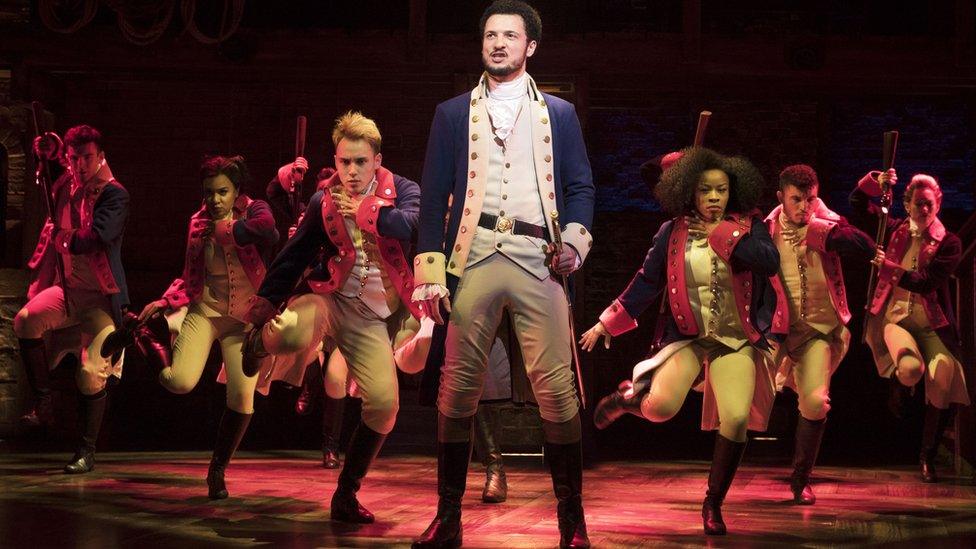

From the first scene, in which we meet Lin-Manuel Miranda (Hamilton) as a cheerful cockney lamp-lighter in "depression-era" London, to a very welcome Angela Lansbury cameo at the end, it seems overawed - starstruck, even - by the Oscar-winning version.

Hamilton creator Lin-Manuel Miranda plays lamp-lighter Jack

It is not helped by the dramatic premise propelling the action, which is as shaky as Lin-Manuel on his Dick van Dyke (if that's rhyming slang for bike - anyway he also has a cameo).

We are back at No.17 Cherry Tree Lane, once home to Mr Banks and his children, Michael and Jane, who Mary Poppins came to look after all those years ago.

It is a few decades later and Mr Banks still lives in his double-fronted mansion. The difference this time is the Mr Banks (Ben Whishaw) in question is the grown-up Michael who has recently lost both his wife and his money. He has taken out a loan to tide him over, but without warning, the bank decides it wants its money back and Michael and his family risk losing their lovely home.

Jane, Michael, John and Georgie greet Mary Poppins upon her return to the Banks' home

This is as much a problem for us as it is for him. Notwithstanding the nasty bank in question happens to employ Mr Banks as it had his father, which makes its aggressive position improbable but just about plausible. But willing us to feel a deep sympathy for a slightly irritating man sitting on a prime piece of London real estate is a big ask.

Frankly, if he can't afford his leafy mansion, do what anybody else would do in his position and flog it to an oligarch or a celebrity and downsize to something a little more modest, like a three-story townhouse in Chelsea.

That doesn't happen.

Instead we see the hapless Mr Banks trying to find a share certificate that will prove his father had purchased some now valuable equity in the bank many years ago. That would solve all his First World problems: he could keep his massive pile in London and have money to burn without having to break sweat.

Fine, but why should we care?

On hand at all times is his sister Jane (Emily Mortimer), who brings much needed warmth and wit to the proceedings, as do all three Banks children who play their parts with an Enid Blyton-type joie-de-vivre.

Unfortunately, Emily Blunt's interpretation of Mary Poppins misses the mark.

Emily Blunt has great presence, but doesn't quite have the magic of her predecessor

I say this as a huge fan of her work, and as someone who had been looking forward to her taking on the role. She's not awful by any means, but her version of the magical nanny is not quite the effervescent, optimistic, can-do cinematic tour-de-force embodied by Julie Andrews.

Blunt's Mary Poppins is a more clipped and angular character, albeit with a winning twinkle in her eye. Her tone is a touch too headmistressy, her knowingness a little too obvious. As for her accent, well that really is something else altogether. It is so ridiculously posh it makes the Queen sound like a member of the EastEnders' cast.

It is when she sings that her Mary Poppins comes alive.

It is too soon to tell if the new numbers will become classics over time - none were instantly memorable - but Blunt and the rest of the cast deliver them with confidence and style.

Frankly, if this were an entirely new venture I suspect it would flounder. But given its heritage and the affection with which the original is held in, Mary Poppins Returns should prove the researchers' rule of thumb that sequels tend to do okay.

- Published23 December 2017