Review: Artemisia Gentileschi - forgotten portrait of artist who endured rape trial ★★★★★

- Published

Great literature can be a good way of gaining an insight into art.

For instance, Rodin's monumental sculpture The Gates of Hell (1880-90) is a complex work that becomes more comprehensible when you realise the artist's source material was Dante's Divine Comedy.

Similarly, it helps to know Ophelia (1851), a painting by Millais, was inspired by Shakespeare's Hamlet.

The same applies to the art world, an opaque place that is occasionally illuminated by a gifted writer such as Tom Wolfe.

But it takes a wordsmith of quite exceptional talent to produce a book to help us understand the truly baffling vagaries of today's art market.

Fortunately there is such a writer.

His name is Roger Hargreaves, and the book in question is his 1972 miniature masterpiece Mr Topsy-Turvy.

Mr. Topsy-Turvy by Roger Hargreaves helps us fathom the unpredictable workings of the art market

No literary character better sums up the bizarre, seemingly cockeyed monetary value placed on art nowadays.

In the book, Mr Topsy-Turvy goes to an art gallery and turns all the pictures upside down. One can only assume he walked happily past the auction houses having noted the sale prices were already the wrong way round.

The amount of money being paid for modern and contemporary art in comparison to the sums fetched by the Old Masters will come to be seen as nonsensical as Pulp's Common People being kept off the number one chart spot by Robson and Jerome in 1995.

Take Christopher Wool, for example. He is a good contemporary artist, But is he $30m good, which is around the figure someone paid at Sotheby's for his text piece UNTITLED, RIOT in 2015?

Maybe.

But if so, what does that make a painting by Artemisia Gentileschi worth, given that she was the greatest female artist of the Baroque period?

Twice as much?

Ten times more?

Rather less, it turns out. The National Gallery in London paid £3.5m for her Self Portrait as Saint Catherine (c 1615-20).

Admittedly, it wasn't in tip-top condition. There was a small tear in the canvas, the image was covered with a layer of yellowed varnish, and there were some obvious paint losses.

The restoration of Artemisia Gentileschi's Self Portrait as Saint Catherine of Alexandria took five months of painstaking work including cleaning the old varnishes

Still, feels like a bargain when you think the gallery could have bought a 1978 Andy Warhol Oxidation Painting for roughly the same amount: a "painting" the artist made by asking a friend to urinate on a canvas.

Instead it went for the Gentileschi, then passed it on to its conservation department to clean and restore before hanging it in the Central Hall alongside a group of other Baroque paintings, where it looks very good indeed. The picture has, as they like to say in auction houses, wall power.

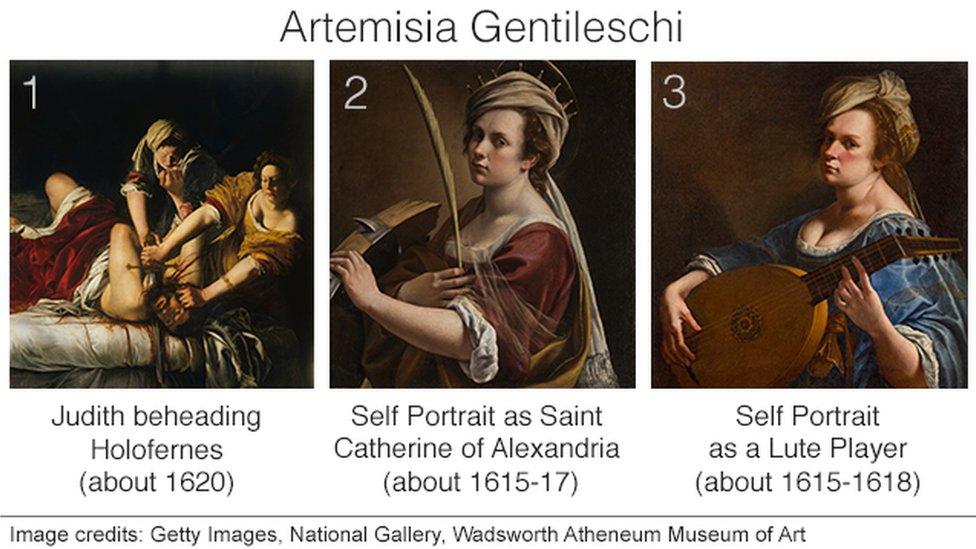

Artemisia Gentileschi brought a female point of view to a man's world and well known subjects. (1)

She often used herself as the model, sometimes as a "self-portrait" of a carefully selected historical figure. She's always making a point. (2)

The idea of presenting yourself partially disguised as someone else such as the Lute Player has been taken on by contemporary, post-modern artists from Cindy Sherman to David Bowie. (3)

It also has a striking back story.

Artemisia Gentileschi was born in Rome in 1593. Her father, Orazio Gentileschi, was an artist heavily influenced by Caravaggio's dramatic "chiaroscuro" lighting technique, where the painter accentuates the contrast between light and dark to model forms and create a sense of theatricality.

Boy Bitten by a Lizard (about 1594-5) by Caravaggio, whose lighting technique greatly influenced both Orazio Gentileschi and his daughter Artemisia

Soon, Artemisia was making her way as an artist in the roughhouse that was 17th Century Rome. She produced her first known work - Susanna and the Elders - when she was about 16.

A year later, she was raped by an acquaintance of her father's called Agostino Tassi, the result of which was a trial that saw Tassi convicted, but only after Artemisia had endured torture to prove she was telling the truth. She left for Florence shortly afterwards.

It was while in Florence she painted the National Gallery picture, in which she presents herself as the Christian martyr Saint Catherine, another woman who had endured torture at the hands of men.

She faces us in a three-quarter pose with an inscrutable expression on her face. Her left hand rests on a broken wooden wheel (Catherine Wheel) inset with metal spikes, an implement that was intended to torture and kill her. Her right hand, which holds the martyr's palm, is held to her chest.

In this painting, Artemisia Gentileschi portrays herself as Saint Catherine of Alexandria, who was also tortured by men

A single light source makes her white sleeve appear to jump out of the picture.

Your eye is then drawn towards the silky red sleeve of her dress and upwards towards her beady left eye, which is giving absolutely nothing away.

The golden arch of the palm is echoed by her halo at the top of the picture, and her shawl at the bottom of the frame.

It is a well-balanced, tonally sensuous painting, which is only slightly compromised by the proximity of the palm to the sitter's face (the same motif is better placed in another version she painted of the same subject, which is now in the Uffizi Gallery in Florence).

For a painting that is almost 400 years old, it feels incredibly modern.

Imagine if the sitter was a contemporary figure like Cindy Sherman, an artist who has also made a career out of depicting herself as other people?

Untitled Film Still #21, 1978, by Cindy Sherman, who like Artemisia Gentileschi, presents herself as other figures

We would read it as a fresh and subversive image.

Which it was and is.

Artemisia Gentileschi was a woman operating in a man's world, making weighty pictures that celebrated and represented women. Her near identical pose in Self Portrait as a Lute Player, and the gruesome depiction of Judith Beheading Holofernes, both show a familiar image from a female point of view.

It is a difference in attitude that can be seen by looking at Caravaggio's painting of The Lute Player and of Judith's murderous act.

Same story, different perspective.

Which brings us back to Mr. Topsy-Turvy.