Will Gompertz reviews John Lanchester's dystopian novel The Wall ★★★☆☆

- Published

The Gompertz guide to... dystopian novels

Betting is a mug's game. We know that. Doesn't stop it being fun, though. We humans have an imagination - speculating on what might happen is second nature to us.

Of course, you wouldn't want to take a punt on something really important when the odds were clearly stacked against you, but a spot of light conjecture about what the future holds is often the basis for a lively conversation.

Is Andy Murray going to retire before Wimbledon? Will Olivia Colman win at this year's Oscars? Does life exist on another planet?

And if you're in the mood for a long night, what's next for Brexit? There's plenty to wonder about there. Britain's future is currently about as predictable as a game of blindfolded darts played by left-handed toddlers using their right arms to throw.

Nobody has a clue as to what is going to happen. Politicians, commentators and pub bores all have a view they will happily share, but nobody actually knows. Which makes the subject fertile ground for novelists, whose stock-in-trade it is to let their imaginations run wild and hypothesise.

Enter John Lanchester, a first-class essayist and now five-time novelist who has written The Wall, a dystopian tale set in a Britain of the near-ish future. Suffice it to say, things have not gone well.

Climate change ("the Change") has done for the country's coastline, which is now beachless and miserable and home to the eponymous Wall: a 10,000km-long, 3m-wide concrete barricade snaking around Britain's perimeter, patrolled by Defenders whose job is to keep out the Others - desperate, homeless migrants from flooded foreign parts.

If an Other succeeds in breaching the heavily guarded Wall, then the Defender considered most culpable is put out to sea in a dinghy never to be seen or heard of again. It's a bit harsh, but rules are rules.

The home guard of Defenders is made up of young men and women who are conscripted through a new National Service. It's a minimum two-year posting of joyless 12-hour shifts with statutory leave taken at home with parents to whom they do not speak because "the olds" are to blame for not only wrecking the planet, but also thoughtlessly bringing kids into a world without beaches.

The book has many of the standard tropes of a dystopian novel. There is a totalitarian state operating in a bleak post-industrial landscape caused by a climatic catastrophe, creating the justification for a faceless bureaucracy to suppress and control a cowed population.

Our protagonist is young Joseph Kavanagh, a new recruit to the Wall. He is about to embark on his stint as a Defender and soon discovers his working environment is grim, a "cold, hard, unforgiving, desperate place" in which he feels "trapped".

The only way to reduce your stint on the Wall is to become a Breeder and have children, which might seem like a no-brainer but… "people don't want to Breed, because the world is such a horrible place." So that's out.

Kavanagh is reasonable company. You wouldn't rush up to him at a school reunion, but he's a steady chap who might be missing a funny bone but at least is willing to engage in some Wall banter with his fellow recruits.

He is not a rebellious type. Nor is he particularly scathing about the State or questioning of its questionable moral compass. For instance, it used to allow a few Others "who showed they had valuable skills" to stay in the country. But not any more, because doing so would escalate the numbers attempting to gain entry.

A self-defeating policy, you might think, at a time when the country is so short of manpower that Kavanagh's miserable two-year stretch on the Wall might have to be extended by another 12 months.

Surely our rookie conscript would be full of righteous indignation, pointing out the contradictory logic of the state: if it was successfully discouraging the Others by being mean, wouldn't that result in fewer and not more Defenders needed on the Wall? It can't have it both ways, can it Kavanagh? Come on man, sharpen up!

But he doesn't. He's a trusting soul, which is always a mistake in a dystopian novel. Fortunately he's a good swimmer.

John Lanchester's novel Capital became a BBC TV drama in 2015

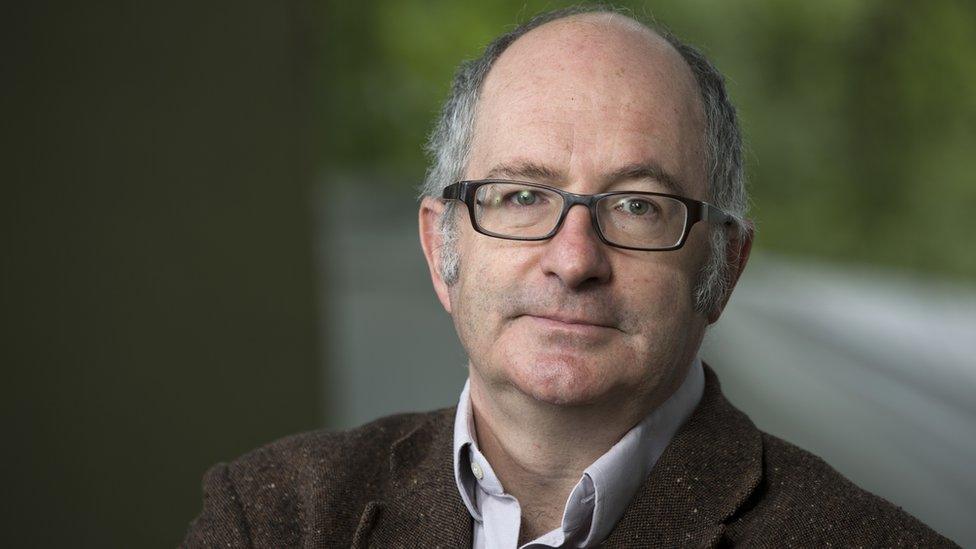

And fortunately for us, John Lanchester is a good writer. As you will know if you've read Whoops! - his non-fiction book about the 2008 financial crisis. He is also a decent novelist. Capital, his previous book - a sort of fictionalised version of Whoops! - did well and was subsequently made into a TV series.

The Wall could well end up on the telly, too. Dystopias are all the rage with producers at the moment: Black Mirror, The Handmaid's Tale, The Hunger Games etc. It would probably require a little something extra, though.

The characters we meet in the book are fine as far as they go, which isn't very far in terms of personality development. They are a low-tech, rather parochial crowd, who aren't nearly as dreary as their environment, but you're unlikely to ever find them showboating in front of a table laden with Big Macs.

Unlike Donald Trump, whose proposed wall is one of the many contemporary political issues Lanchester deftly alludes to in a book that owes more to One State's all-encompassing protective Green Wall in Yevgeny Zamyatin's early 1920s dystopian classic We than it does to the current US president's border project.

John Lanchester

The novel We inspired an entire body of so-called speculative fiction including Brave New World and Nineteen Eighty-Four. All are great works. Which The Wall isn't, quite.

It is very good: a well-structured, well-paced story with a narrative drive that keeps you going through the monotony of life on the Wall. It does, though, fall a concrete slab or two short in terms of its ambition, both intellectually and imaginatively.

It doesn't stretch or challenge the reader or use the future as a device to introduce any alarmingly new social concepts (beyond the idea of the devastating effects of global warming, evidence of which is already just a Google click away).

In fact, I suspect if John Lanchester were to use his learned, measured, insightful mind to produce a non-fiction book about climate change, it would be a far more distressing peek into the future than his latest novel.