Will Gompertz reviews When We Have Sufficiently Tortured Each Other ★★★★☆

- Published

Gruesome theatre... Will Gompertz on plays that will (probably) make you faint

Life is full of disappointments. The rain-soaked summer holiday. A terrible blind date. Passport photos. Politicians. We know, let-downs are inevitable.

Obviously, we do our best to avoid them.

For example, if you were going to splash out on a night at the theatre to see a new play, you might want to check out the talent first.

If one of the actors was a two-time Oscar-winner whose work you greatly admire, playing opposite a first-class character-actor who's just been in a hit TV show, you might be inclined to give it a go. Especially if you also spotted it was being staged by one of the finest theatre directors in the country, at the National Theatre, and had been written by a leading playwright.

You might even feel a little smug that you had a ticket to the sold-out show when others were queuing from 4am in the hope of buying one of few made available on a first-come-first-served basis every day.

That was certainly the vibe in the house on Wednesday at the National's Dorfman Theatre for the opening night of Martin Crimp's latest play, When We Have Sufficiently Tortured Each Other: his riff on Samuel Richardson's 18th Century novel, Pamela.

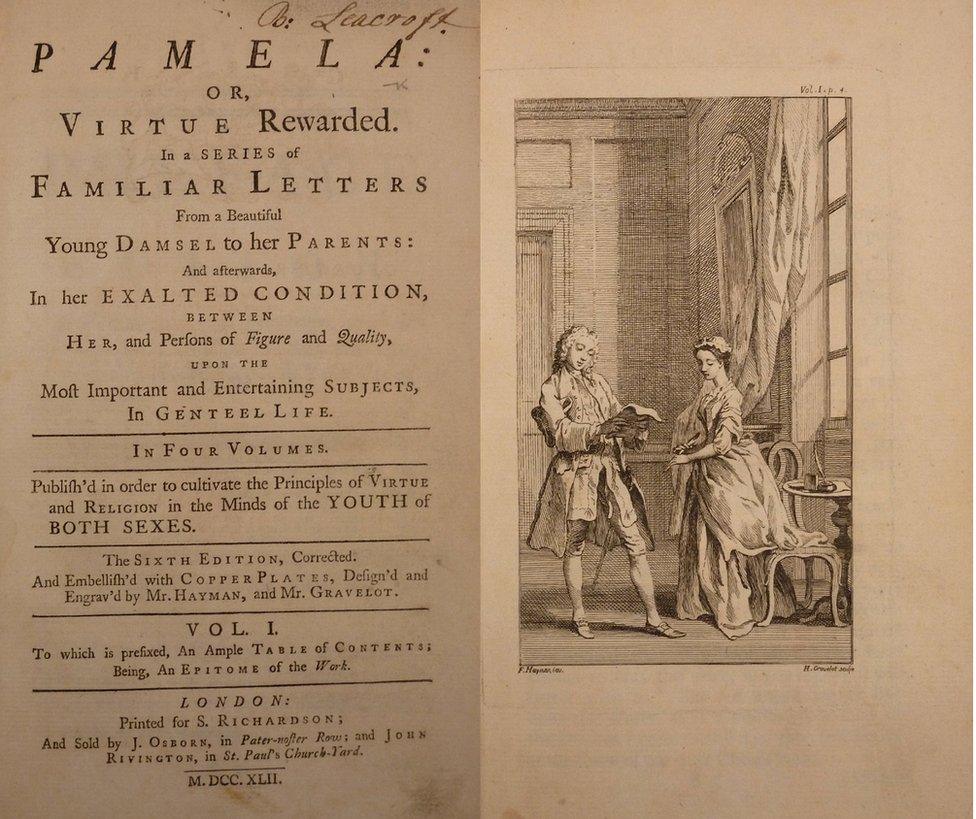

Martin Crimp's play draws on the novel Pamela, which shocked 18th Century society

The book caused a sensation when it was published in 1740, what with its 15-year old protagonist Pamela, being abducted, abused and threatened with rape by Mr. B, a charismatic libertine with a very nasty streak.

There had been talk of the play being even more outrageous, with scenes of sex and violence so graphic theatre-goers were fainting.

Hence, a palpable sense of expectation as the audience waited for the actors to enter the stage, which had been transformed into a suburban double garage with a black Audi parked in one bay, and a fridge and a few chairs scattered about in the other.

That sense of anticipation went up several notches when Cate Blanchett (The Aviator, Blue Jasmine) appeared in a dark blue dressing gown with black masking tape covering her mouth.

Woman's (Cate Blanchett) turn to be in the driving seat as she engages in sadomasochistic power games

And then Stephen Dillane (Game of Thrones) entered, accompanied by a menacing-looking small gang, all of whom were similarly gagged. It felt very ominous. You could almost hear the audience collectively buckling up.

This was going to be a shocker.

And so it turned out to be.

A shockingly disappointing play.

At least, it was in terms of it being a play in the conventional sense. Blanchett and Dillane, the two main characters, are known to us only as Woman and Man. They spar continually, each taking turns to be the dominant character, while constantly changing and swapping clothes and identities in two hours (without a break) of sexualised role-play.

Stephen Dillane and Cate Blanchett role play as groom and bride

Sometimes they get into the car and thrash about a bit and argue, sometimes they sit in chairs and thrash about a bit and argue.

She writes, he whinges; he boasts, she whinges.

They are both unbearable bores.

They are watched throughout by four youngsters who also change roles at the flick of a light switch. Mrs Jewkes (Jessica Gunning), one of the gang, plays the role of the complicit Housekeeper from Richardson's novel, except here she is brandishing a whip and trying to get off with Woman.

There are occasional moments of sex and violence, which are more hammy than horrid. I couldn't see anything obviously faint-inducing as has been reported. Maybe the person who witnessed such an occurrence was mistaken and the audience member in question had simply nodded off (someone behind me was snoring very loudly).

Foreboding background music is played throughout to generate a sense of unease and imminent danger. It works. An air of suspense hovers over the production like a dark cloud.

Except nothing ever happens.

The whole thing is a tease.

Which is the point of course. That's what the two middle-aged, self-obsessed, S&M lovers like to do when dressed up in their matching French maids' outfits. Their chosen form of torture is more the psychological kind rather than physical.

That said, there is one moment early on when Woman allows herself to be the victim of violence, which Cate Blanchett plays to perfection.

In fact, she is excellent throughout. As is Stephen Dillane and the rest of the cast. Added to which, so is Katie Mitchell's directing and Vicki Mortimer's set. The problem isn't with them, it is with the play.

Cate Blanchett as Woman, dressed up for sexualised role play

Stephen Dillane as Man, he too has a French maid's outfit - underneath the suit!

Babirye Bukilwa and Emma Hindle as Girl 1 & 2, voyeurs and occasional participants in the dark games played by Woman and Man

Jessica Gunning as the complicit Mrs Jewkes, part-time housekeeper, enforcer, and when needed, priest

A black Audi car inside which some of the action takes place

Wine glasses on top of a fridge. Woman likes a drink… or two

It just doesn't work as a piece of theatre in the traditional sense. You don't care about the characters, the dialogue is tedious, and the dramatic elements are clunky.

An out-and-out flop, then?

Err. No. Not at all. Quite the opposite, actually.

Approached another way, not as a regular play in a theatre but as a piece of performance art installed within a proscenium arch, When We Have Sufficiently Tortured Each Other becomes a very different thing. The need to suspend disbelief recedes, as does the desire to be entertained.

The fact that it is disjointed, knowingly performative, and more interested in exploring textual ideas than sexual mores, becomes a delight not a downer.

Woman dressed in her blood-splattered wedding gown after a sexual encounter

Encounter it as a piece of site-specific art frees you up, it allows you as a viewer to engage with the work in a different way; your expectations change: your relationship with it is on a different footing.

And from that point of view it is a very successful, intellectually challenging, exploration of the spoken and written word. It isn't so much about gender dynamics, which might be the obvious reading of the play, but more about the shifting power and effects of language.

So, all that incessant banter between Woman and Man suddenly becomes endlessly fascinating, because it is the talking, the words, which are the essential subject of the piece, rather than simply being a device for describing the action taking place.

The text is the scaffolding around which Martin Crimp builds what amounts to short vignettes to investigate how the meaning of words and language change when seen and heard from different angles. And how that, in turn, might affect us emotionally, intellectually or psychologically.

There is so much to explore in this complex, complicated, atypical work. If you go expecting a classic three-parter with a conventional plot and dramatic arc, you will be disappointed. In fact, I suspect you'll hate it.

If, however, you're up for a work of art that is difficult, oblique, frustrating, and at times tedious - in other words, hard work - then set your alarm clock for 4am and start queuing.

I'll see you there.