The rock stars of poetry explain why the art is in demand

- Published

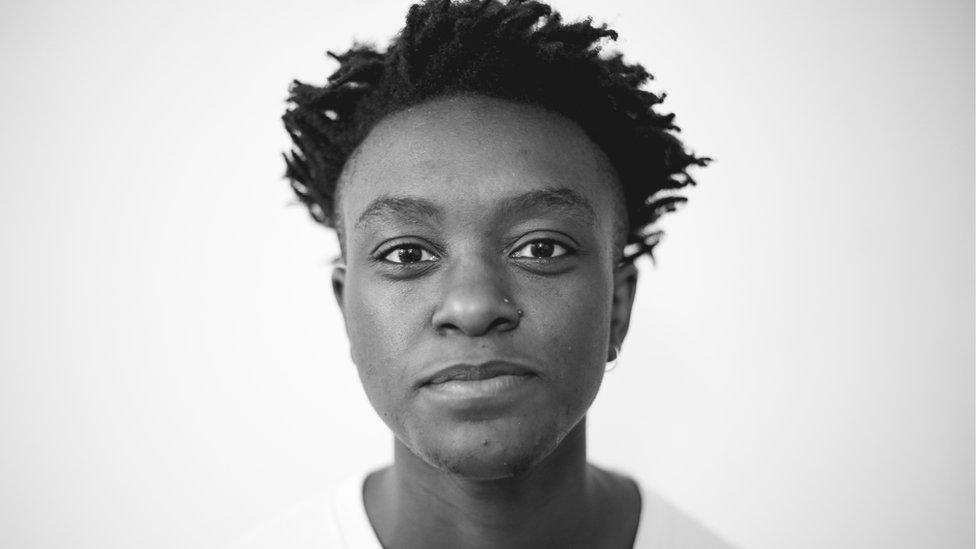

Jay Bernard's first collection, Surge, is published in June, but has already won an award

Jay Bernard's teenage poetry was terrible, something the award-winning poet is happy to admit.

The 31-year-old south Londoner began writing at school, printing out poems, stapling them together, and charging classmates £2 for a copy.

More than a decade later, Jay, who self-describes as non-binary, has won the 2018 Ted Hughes Award for Surge: Side A, an exploration of the New Cross Fire in 1981 - which killed 13 young black people in south-east London.

Jay's poetry is personal and explores identity, politics, and what it means to be young and black in Britain.

According to Susannah Herbert of Forward Arts Foundation, which runs National Poetry Day and the Forward Prizes for Poetry, Jay is part of the changing face of poetry.

Ten or 15 years ago, Susannah says, the major UK publishers and booksellers knew little about the poetry audience and tended to assume "real" poetry was highbrow, niche, and plainly presented with no pictures or introductions.

But last year poetry book sales increased by £1.3m - and two-thirds of buyers were younger than 34, according to statistics from Nielsen BookScan.

Susannah believes the increase in poetry sales is linked to changing attitudes towards sexuality, race and gender - forcing poetry, like many other industries, to become more relatable.

"Social media has changed this: now that we can track poetry shares and likes, we can see a huge, mass, need for words that matter, words that touch on truth," she says.

"So when news footage of the black, non-binary, Danez Smith reading Dear White America gets viewed 300,000 times on YouTube in 24 hours, it makes immediate sense for a long-established publisher like Chatto & Windus to publish them."

According to Susannah, 30 years ago poets from black and other ethnic-minority backgrounds were virtually invisible.

She says that, before social media, "a handful of middle-aged men in high places set the tone, publishing poetry they liked to read and, often, to write themselves".

Jay agrees: "At one stage in the UK, if you knew about poetry it was probably because you had an elitist education, and people have started to challenge that.

"They now want to see an open and democratic approach to poetry."

Arrival

By Jay Bernard, coming from the forthcoming collection Surge, published by Chatto and Windus in June (poem contains language some may find offensive).

remember we were brought here from the clear waters of our dreams

that we might be named, numbered and forgotten

that we were made visible that we might be looked on with contempt

that they gave us their first and last names that we might be called wogs

and to their minds made flesh that it might be stripped from our backs

kept hungry that we might cry in our children's sleep

close our smokey mouths around their dreams

swallow them as they gaze upon us

never to be full -

snap, crackle

amen

Not only are sales of poetry books up by almost 50% since 2014 (£12.3m in 2018, compared with £8.3m in 2014), Instagram also featured more than 27 million posts using the hashtag #poetry last year.

Among those who self-publish on Instagram is Ashanti Wheeler-Artwell, a 25-year-old mixed-raced, working-class spoken word poet.

Growing up in Oxford, she started writing poetry at the age of nine, and went to what she describes as a "very white and very middle class" school.

Ashanti says finding relatable poets online gave her the courage to perform

She said she studied poetry at school and remembers a GCSE anthology called English: Poems From Other Cultures, but recalls her surprise when the photos used in the textbook only featured white writers.

"It was crazy, what were four white faces doing on a multicultural anthology?" she asks.

"I loved the poets we studied at school, but partly because I had fantastic teachers. Now when I look back, I didn't realise that you can access different types of poets.

"For example, without the internet it would have been years before I discovered Maya Angelou, and other amazing black poets. I wouldn't have known there were spaces to discuss the issues that are important to me, such as class and race etc."

Ashanti, who has struggled to make an income from her poetry, said she wouldn't have considered a career in the industry before the internet - partly due to the fact that she had never seen black women performing poems they had written.

But then she discovered them online and says: "It gave me courage to perform. People don't realise that it is actually very difficult, as a black woman, to get up and talk about race - in a room full of white people."

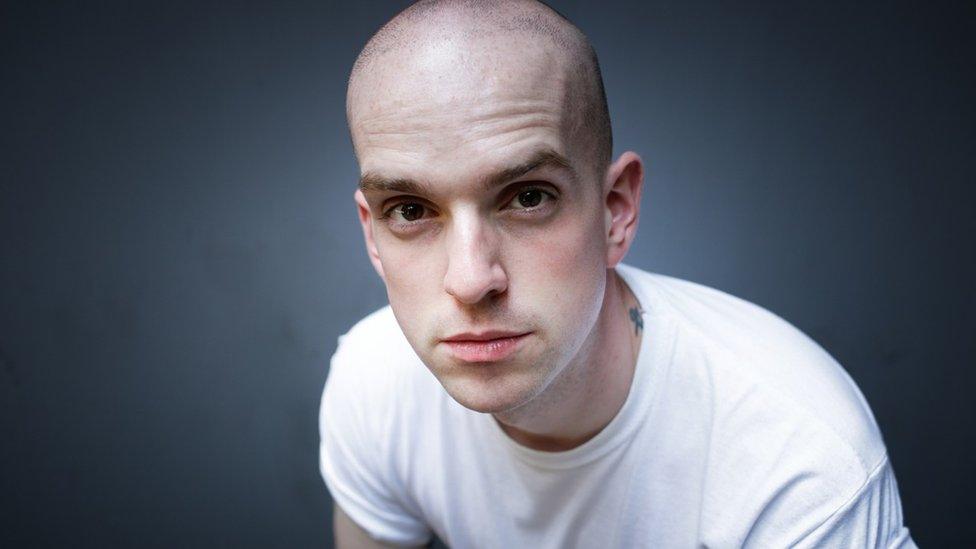

Andrew McMillan writes about bodies and says he is inspired by the unpoetic

Unlike Ashanti, Andrew McMillan, 30, grew up in a house where books of contemporary poetry were on his family's bookshelves. But the 30-year-old from South Yorkshire agrees that attitudes towards poetry have changed.

Andrew's debut collection, Physical, was the first poetry collection to win the Guardian First Book Award.

The award-winning poet and senior lecturer at Manchester Metropolitan University says that, although more young people are buying poetry books, the industry isn't lucrative, as many poets still need part time jobs to fund their passion - unless they are already "independently wealthy".

Perhaps because of this, he believes poetry will always be niche, but that social media has made poets and poetry more accessible.

He explains: "The form has adapted to different technology, but poems and poetry has become more freely available."

He says the "very serious, very anxiety-inducing, dangerous times" also have a part to play as the world enters "a very difficult decade of geo-politics" as he describes it.

"Poetry becomes a way to stand back, to bear witness, to contemplate."

- Published24 June 2018