Will Gompertz reviews Christian Dior: Designer of Dreams at the V&A ★★★★★

- Published

Three ways Dior changed fashion forever

On Wednesday 12 February 1947 at around 09:45, a queue of insanely glamorous people stood outside 30 Avenue Montaigne, Paris, shivering in temperatures below -5C.

Among them was the artist Jean Cocteau, the socialite Lady Diana Cooper and the editors of American Vogue and Harper's Bazaar.

It was the coldest winter in a generation. They were freezing.

Meanwhile, inside the recently derequisitioned house, people were scurrying around adding the finishing touches to a radical new womenswear fashion collection.

Tensions were running high.

It was the launch of an haute couture label thought to have cost millions of francs.

At 09:59, a portly, middle aged man with a passing resemblance to Alfred Hitchcock walked between the countless flower arrangements installed throughout the house, calmly spraying the scent that Paul Vacher had created for him to set the tone of his eponymous business.

At 10:00 precisely, he instructed a member of his staff to open the front door.

The 42-year old host, whom the photographer Cecil Beaton described as "a bland country curate made out of pink marzipan", welcomed each guest individually and invited them to relax before the presentation of his highly anticipated first collection.

Everything was arranged perfectly.

It had to be.

That was this particular man's way: it was the mark of Christian Dior.

Christian Dior's first collection in 1947 was the hottest show in town

You can find out what happened next at the V&A in London, which is presenting a retrospective of the Dior label's subsequent 72 years among the international fashion elite.

It starts where the story stops at 30 Avenue Montaigne.

Christian Dior knew that the townhouse at 30 Avenue Montaigne in Paris would be the home to his couture label

As you walk up to the imposing front door, your way is blocked by a black mannequin wearing the two-tone two-piece that defined both that inaugural 1947 show and Christian Dior.

The Bar Suit caused a sensation.

It was an extravagant, rebellious response to the grim austerity of post-war Europe. Instead of a dull boxy jacket and no-nonsense skirt that required minimal fabric or imagination to make, Dior presented a soft-shouldered, wasp-waisted silk jacket fanning out over the hips to reveal a long, dark blue pleated skirt, which took many metres of fabric to produce.

With its feminine silhouette, the Bar Suit (1947) became the the emblem of the New Look

It was outrageously decadent in an era of rationing, but also fabulously exciting: a vision for the future that was colourful, opulent and beautiful.

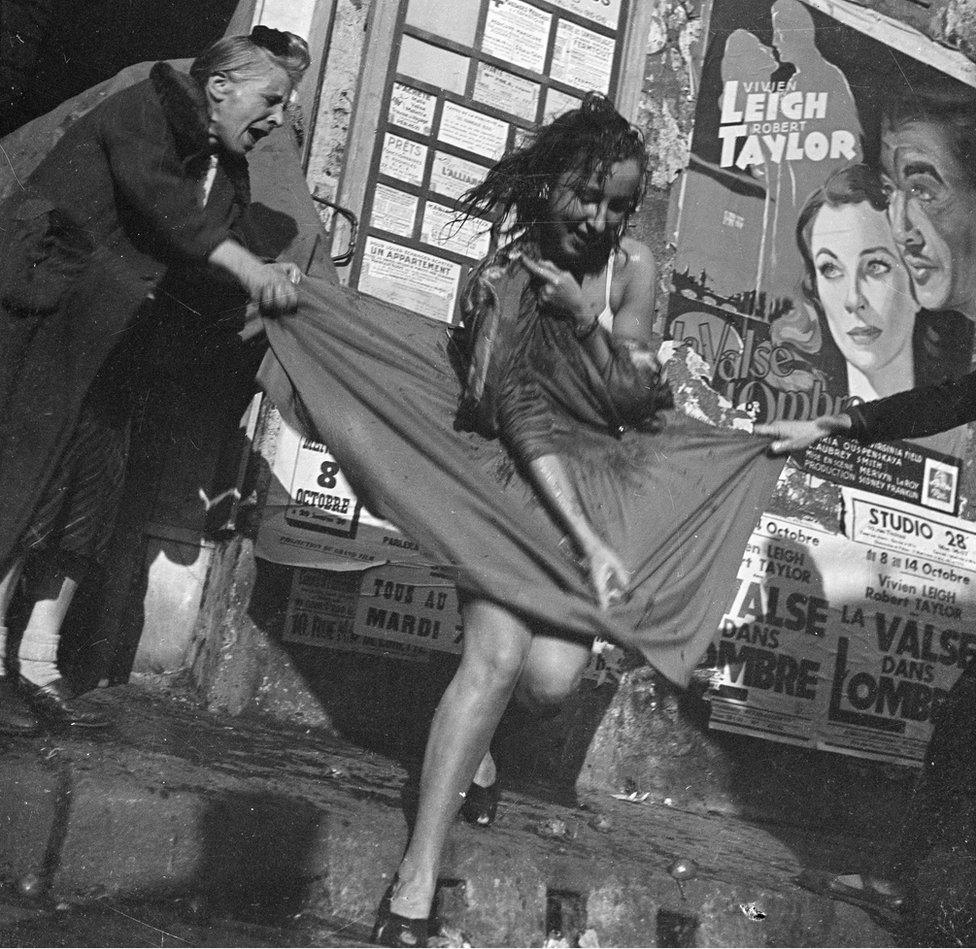

The politicians hated it, as did some members of the public who notoriously spat at and attacked models wearing Dior. There was even an incident, famously captured by the photographer Walter Carone, where a young woman was set upon and stripped by two older ladies of the "make-do-and-mend" school who were appalled by what they perceived as her wanton wastefulness.

Walter Carone captured the moment a young woman had her clothes torn off by women outraged at what they saw as a waste of fabric

The fashionistas saw things differently. They absolutely loved what was immediately known as the New Look.

Christian Dior had arrived.

Why his work had such an immediate impact is obvious when you step over the threshold and into the first gallery. The designs he produced and the fabrics he used were the epitome of old-school glamour, with elegant lines - or silhouettes - cut from luxurious materials. They are a wonder to behold, at least on the outside.

I imagine the whalebone corsets and under-wired structures needed to retain the shape felt neither elegant nor luxurious. Still, Il faut souffrir pour être belle, as they say.

Christian Dior with model Lucky, circa 1955

Princess Margaret commissioned the Frenchman to make her 21st birthday dress; here - at last - was a designer producing clothes for modern young women, not rich old ladies.

The gown he produced for Margaret is displayed beside Beaton's famous photograph of the princess modelling it, behind which is a double-decker display case of the dresses Dior made for other members of Britain's next-gen high society.

Christian Dior designed this dress for Princess Margaret, which she wore for 21st birthday celebrations

When you enter the third gallery, everything changes… for a reason. Christian Dior is dead.

A decade after that cold February morning in 1947, the designer, who had by now become a household name, suffered a fatal heart attack in Italy.

There was talk of closing the business, but Dior had a 21-year-old assistant who was showing some promise, so the board decided to give him a go.

Yves Saint Laurent didn't let them down.

You can see his Dior design classics mixed with those produced by the five creative directors who followed him, including pieces of Baroque ebullience by John Galliano. They all have their own idiosyncratic style, but there is a "Diorness" that unites them, which is most apparent in the display of their re-imagined Bar Suits.

Yves Saint Laurent was just 21 years old when he was appointed Dior's creative director, but didn't disappoint

John Galliano at Dior pushed the definition of haute couture with his extraordinary and lavish designs

Themes rather than chronology take you through the rest of the exhibition.

There are galleries dedicated to historicism, the garden, the ateliers and, finally, a glitzy ballroom featuring animated glitter erupting across the ceiling and down the walls. The effect is only marginally compromised by non-slip rubber matting underfoot rather than a sprung wooden floor polished for dancing.

Christian Dior wasn't known for skimping on costs, and nor has the V&A.

The museum created a rod for its own back with its blockbuster Alexander McQueen show in 2015. It changed visitor expectations forever. A couple of display cases of some nice dresses won't cut the mustard nowadays - punters want a theatrical experience to remember and post on Instagram.

And curator Oriole Cullen has delivered just that. This is a fantastic show that builds from a modest scrapbook of family photos at the beginning to a climatic end with over 70-years of creative excellence displayed in the round.

It is an unashamed celebration of Christian Dior's joie de vivre.

This is by far the most successful exhibition to be held in the museum's recently-opened subterranean gallery. It is a space that would make a decent parking lot, but is a fiendishly difficult place to programme. To give visitors any sense of a narrative flow requires the construction of an inner world that costs, I am told, an eye-watering amount of money.

Still, the Kensington institution is expecting a lot of people to come and see the show over the next six months, and so - in the spirit of Christian Dior - it has chosen to invest heavily in Nathalie Crinière's exhibition design.

Notwithstanding a hairpin bend in the third gallery, she and her team have pulled it off with aplomb and presented an environment that I suspect Christian Dior would not only recognise, but would wander through merrily spraying his Miss Dior perfume.