Will Gompertz reviews Jeff Koons at the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford ★★★☆☆

- Published

The Gompertz guide to... Jeff Koons

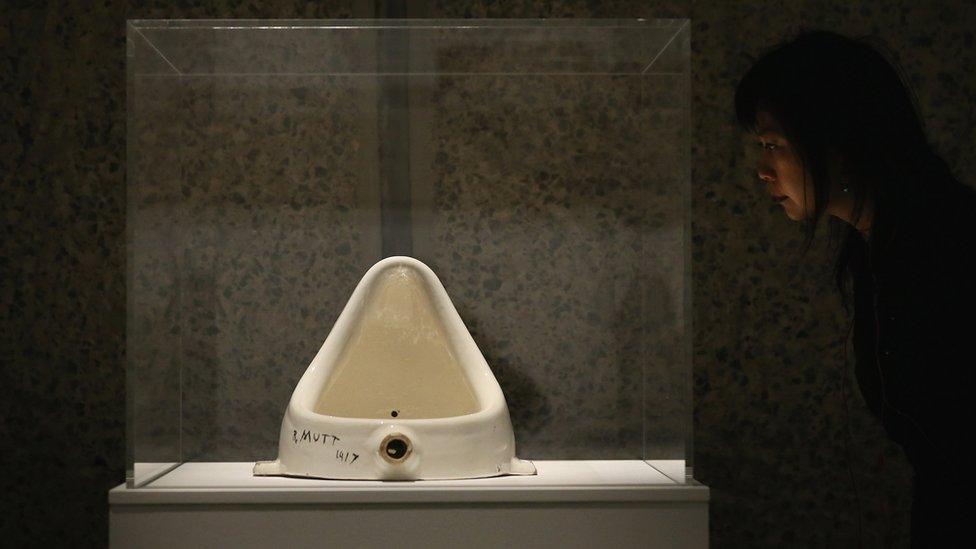

Ever since that old rascal Marcel Duchamp purchased a flat-backed Bedfordshire urinal in 1917 and proclaimed it a "readymade" sculpture, art has become a game of context.

It is no longer solely defined by materials used (a painted canvas, a carved stone) but also by where something is shown. And so, an unmade bed is a slovenly disgrace at home but a $1m installation in an art gallery.

Marcel Duchamp changed the way we look at art with his Fountain, a porcelain urinal in 1917

Location, location, location - as the art dealers and estate agents of Mayfair like to say. It's a mantra that's given curators a new lease of life. They can now be the authors of the surprising juxtaposition, the creators of arty odd-couplings such as putting Grayson Perry's pots in the British Museum or having Banksy take over the Bristol City Museum.

And now, in a similar vein, we have Jeff "kitschy" Koons at the venerable Ashmolean in Oxford. It is the oldest public museum in the country and the permanent home to 3,000-year-old Early Cycladic sculptures and delicate Raphael drawings, which, until 9 June, will be sharing their des-res with the American artist's giant candy-coloured, stainless-steel "inflatables" and mildly pornographic paintings.

It is quite a coup for the Ashmo. Koons is a big-shot, celebrity artist who normally shows up at fancy modern art museums. He is not normally a provincial city sort of guy.

Oxford is a-buzz.

Tickets are selling fast.

Expectations are high…

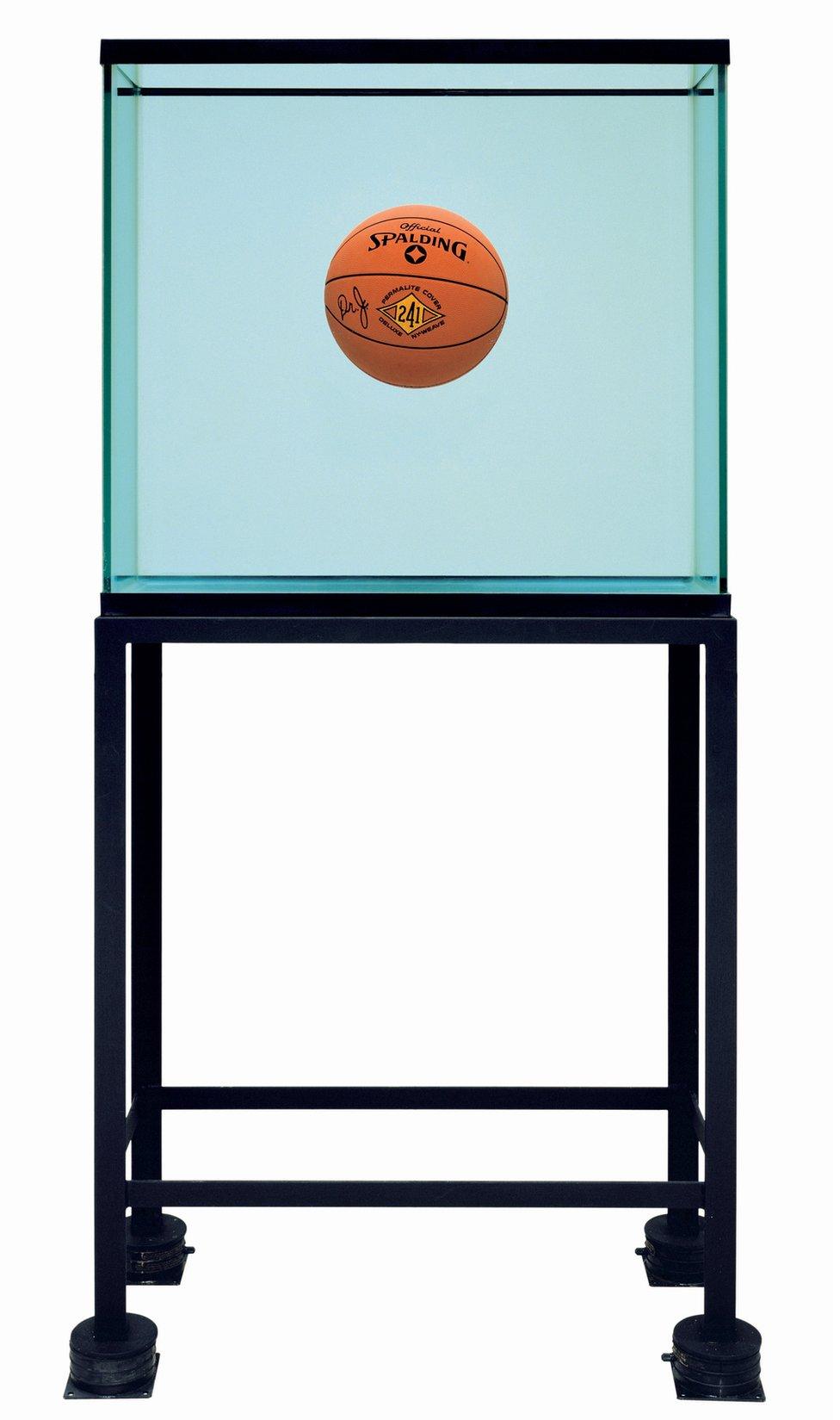

And they will remain so as visitors encounter the first work in the first room, which is from his early 1980s Equilibrium series. The piece consists of a single basketball suspended in a tank of water like a foetus in a womb. It looks good now, but imagine how such a precise, sparse work must have appeared back in 1985 when shown in a small Manhattan gallery at a time the city was full of overblown paintings by macho neo-expressionists.

One Ball Total Equilibrium Tank (1985) is a basketball in a tank of water, which Koons described as being in a "pure state like birth"

It was like a palate cleanser.

An unfussy sculpture that eloquently captured the spirit of Duchamp, Warhol and the 1960s minimalists (Donald Judd and Robert Morris), while pointing to a way forward in which contemporary art could continue to elevate the everyday to the eternal.

One Ball Total Equilibrium Tank epitomises the best of the New York-based artist. It is deceptively simple, painstakingly executed, and intellectually ambitious: a well-balanced combination of new ideas and art historical influences.

The second sculpture in the room starts to make the £12.50 ticket price look like a bargain.

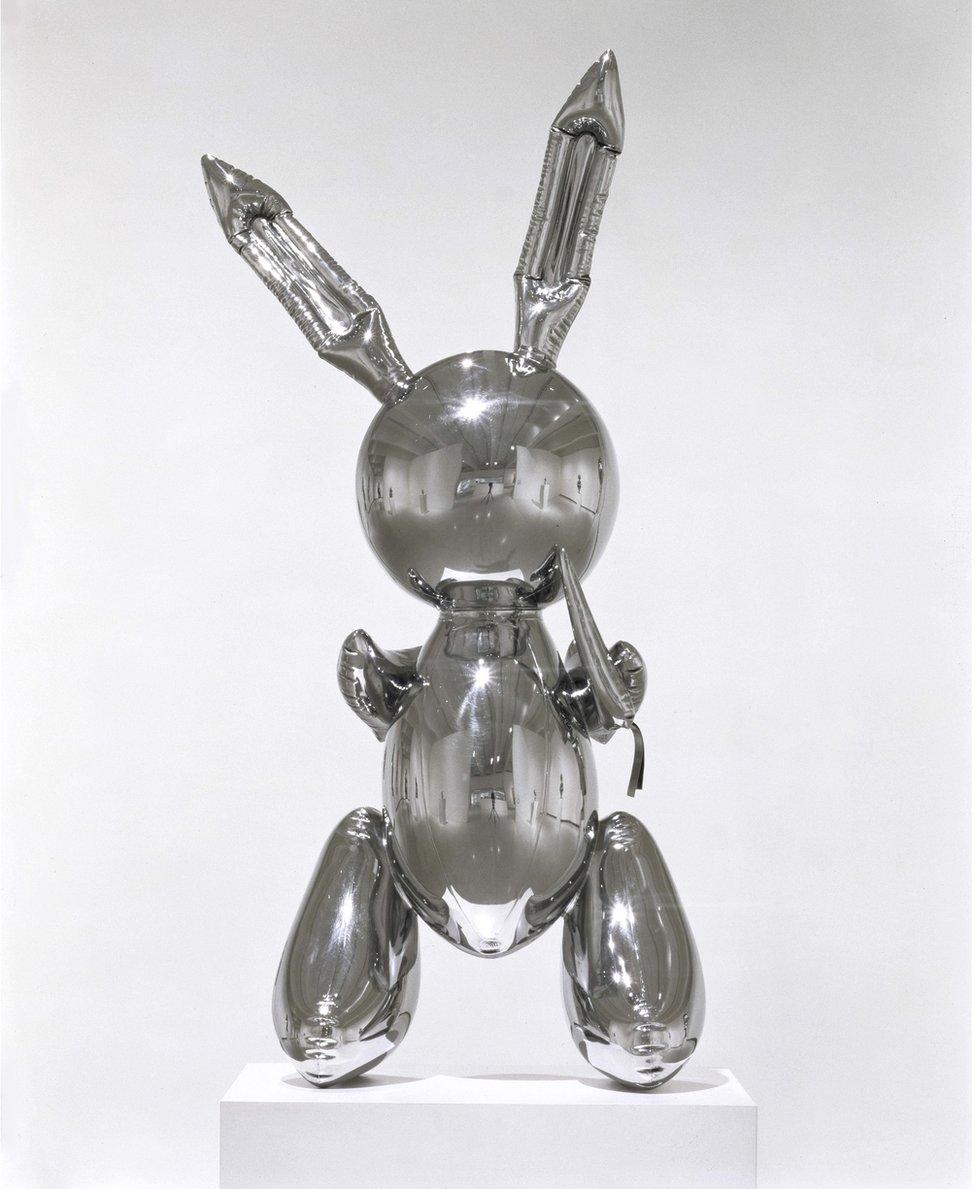

Rabbit (1986) is classic Koons: a 3ft high polished stainless-steel bunny made to look like a helium balloon. It is a trompe l'oeil of sorts, an illusion: a cheap, vinyl, inflatable toy that is actually the very opposite.

Koons made his name through the appropriation of popular imagery with works like Rabbit

This is pop art with a surrealist edge.

Things are not what they appear to be.

A children's toy laden with sexual overtones, a blow-up figure that would break your toe if dropped. Like the basketball, it has the appearance of a buoyant object full of air but would sink faster than Venezuela's economy if used as a float. And that's not a totally spurious analogy.

Rabbit is partly about economics. It questions value and how it is attributed, it speaks to consumerism, and plays with the transformation of cheap, undesirable materials into a sought-after, expensive object.

It is concerned with the disposable and the permanent, and, of course, context. The object, which could be mistaken for the Playboy logo, or a piece of in-store promotion, is presented as a work of art to sit alongside Michelangelo's David in the great canon of western sculpture.

The Renaissance master, Michelangelo is one of the many artists to have inspired Koons

And then there's all the stuff about art reflecting life and life itself (you) being reflected back when looking at the Rabbit. Koons adds to these multiple interpretations by saying his "inflatables" are imbued with the life-giving property of air, and that "we are all inflatables".

There's more, about Platonic forms, optimism, and self-knowledge. But enough. You can over-analyse these things and lose sight of the art. Rabbit might or might not mean some or all of these things to you. It doesn't really matter. The point is that it succeeds on its own terms, as an object with aesthetic and intellectual merit.

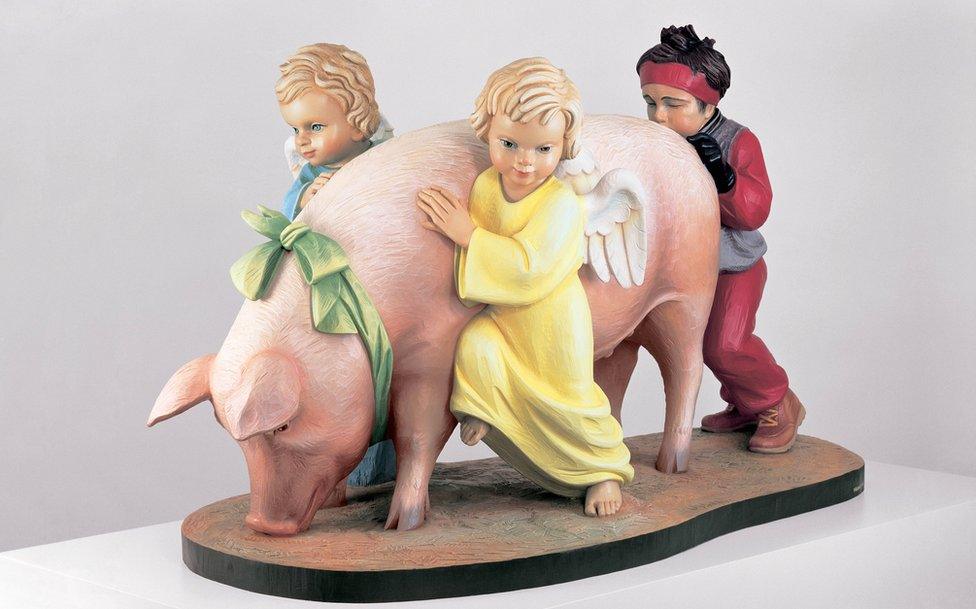

As does Ushering in Banality (1988), in which the artist has reduced himself to a figure on a trinket pushing a pig. It is the third sculpture in the row straight out of Koons's Greatest Hits album.

With Ushering in Banality (1988), which re-imagines mass-produced trinkets and figurines, Koons said he wanted to make works that embraced people's cultural history

The ticket price is already vindicated.

Which is a good thing, because a lot of what follows is… balls.

Literally.

There's much enjoyment to be had from looking at Jeff Koons's early works, but precious little from gazing at his balls.

The bright blue orbs are dotted about like flea-bites from a hostel. They keep popping in unexpected places. The first one is sitting atop a white plaster bird bath at the end of the first gallery, striking an off note in an otherwise excellent display.

Jeff Koons works in series, with this particular "gazing ball" chapter starting in 2013. It worked a treat when used as part of a montage he made for Lady Gaga's ArtPop album cover, but has since petered out into rather insipid installations that mark a low point in the artist's 40-year career.

The third gallery is dedicated to his gazing balls.

Some have been placed on plaster reproductions of statues from classical antiquity such as the Belvedere Torso, which work OK in that "surprising juxtaposition" sort of way, but those that have been placed in front of reproductions of famous paintings like The Tiger Hunt (1615 -16) by Peter Paul Rubens miss by several miles.

With Gazing Ball (Rubens Tiger Hunt), Koons says he's paying homage to our forebears

Gazing Ball (Mailbox) along with the earnest exhibition label beside it, is so pompous it's unintentionally funny. No matter. The whopping stainless-steel sculptures in the second gallery amuse in a good way (unlike the unconvincing paintings lining the walls, which feel like padding).

The giant magenta Balloon Venus (2008 - 12) that dominates the far end of the space will live long in the memory of Ashmo goers. It is fantastically incongruous and perfectly apt, harking back as it does to the tiny Paleolithic stone statuette known as the Venus of Willendorf.

His Venus works well in the gallery.

Balloon Venus (Magenta) is made with Koons’s signature motifs: monumental scale, inflated balloon and the mirror-polished surface

Balloon Venus (Magenta) was inspired by this tiny Stone Age fertility figure known as the Venus of Willendorf

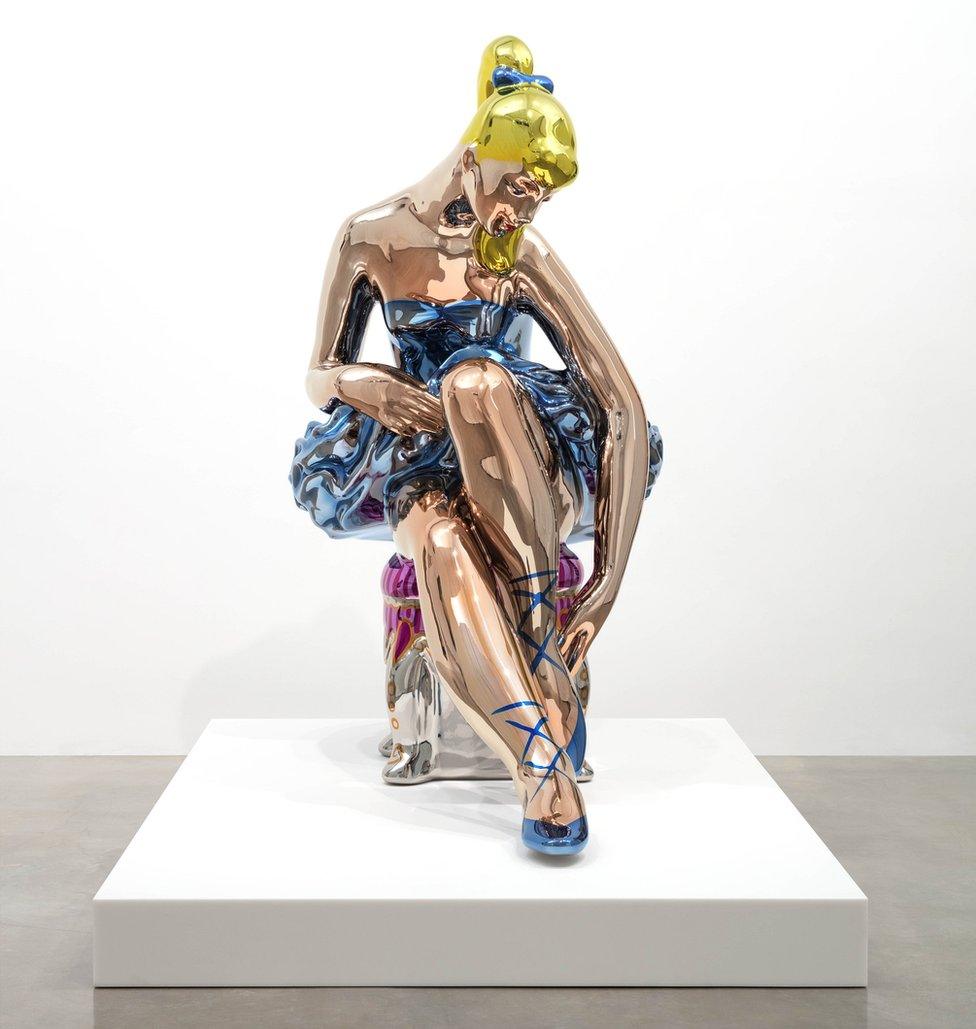

It would work even better if placed among the statues and casts from classical antiquity that are displayed in the permanent collection. Instead it shares the space with two of his monumental ballerina pieces presented in mirror-polished stainless steel.

Art history is at play again, with an obvious nod to Degas, but these are also a celebration of high-tech.

Koons created Seated Ballerina with stainless steel, which he describes a "proletariat material" that is then polished to make it "visually intoxicating"

His team in Germany who fabricate the pieces have gone to extraordinary lengths to create seamless objects for your eyes' desire. But they're not attractive, they are spooky: massive blow-up dolls that are surrounded by porny paintings, all of which has been overseen by a very rich man well into his 60s.

What was once subversive has now become crass.

It's a shame. Because the show starts brilliantly, but too quickly fades into a tawdry and insipid display of very shiny but rather dull art.