Will Gompertz reviews photographer Diane Arbus at London's Hayward Gallery ★★★★★

- Published

The Gompertz Guide to...Diane Arbus

They say you can judge people by the company they keep. Oligarchs hang out with art dealers, yacht brokers and muscle-bound bodyguards. Fading film stars winter in Miami among plastic surgeons and country club members. Undertakers chauffeur the dead. But who - outside the Houses of Parliament - would choose oddballs, misfits, and exhibitionists as their squad?

Step forward Diane (pronounced Dee-Anne BTW) Arbus. The American photographer loved an eccentric like a salesman loves a sucker. They were her people: outsiders of all shapes and sizes - short, giant, obese, skinny - who had the courage and character to expose their vulnerability in front of her searching lens.

Diane Arbus poses for a rare portrait with her beloved camera in New York, circa 1968

You don't just look at the subjects of Diane Arbus's photographs, you meet them. Her New York street photography was quite different from the images produced by the likes of Walker Evans and Robert Frank, who were also documenting mid-century urban America.

She wasn't a click-and-run flâneur surreptitiously snapping away from a camera buried within an overcoat, or one poking out from the passenger window of a passing car.

An Arbus image was the product of a collaboration between the seer and the seen: the photographer and the photographed.

She would spend hours, days even, building a rapport with the strippers, inkers and razorblade swallowers she portrayed.

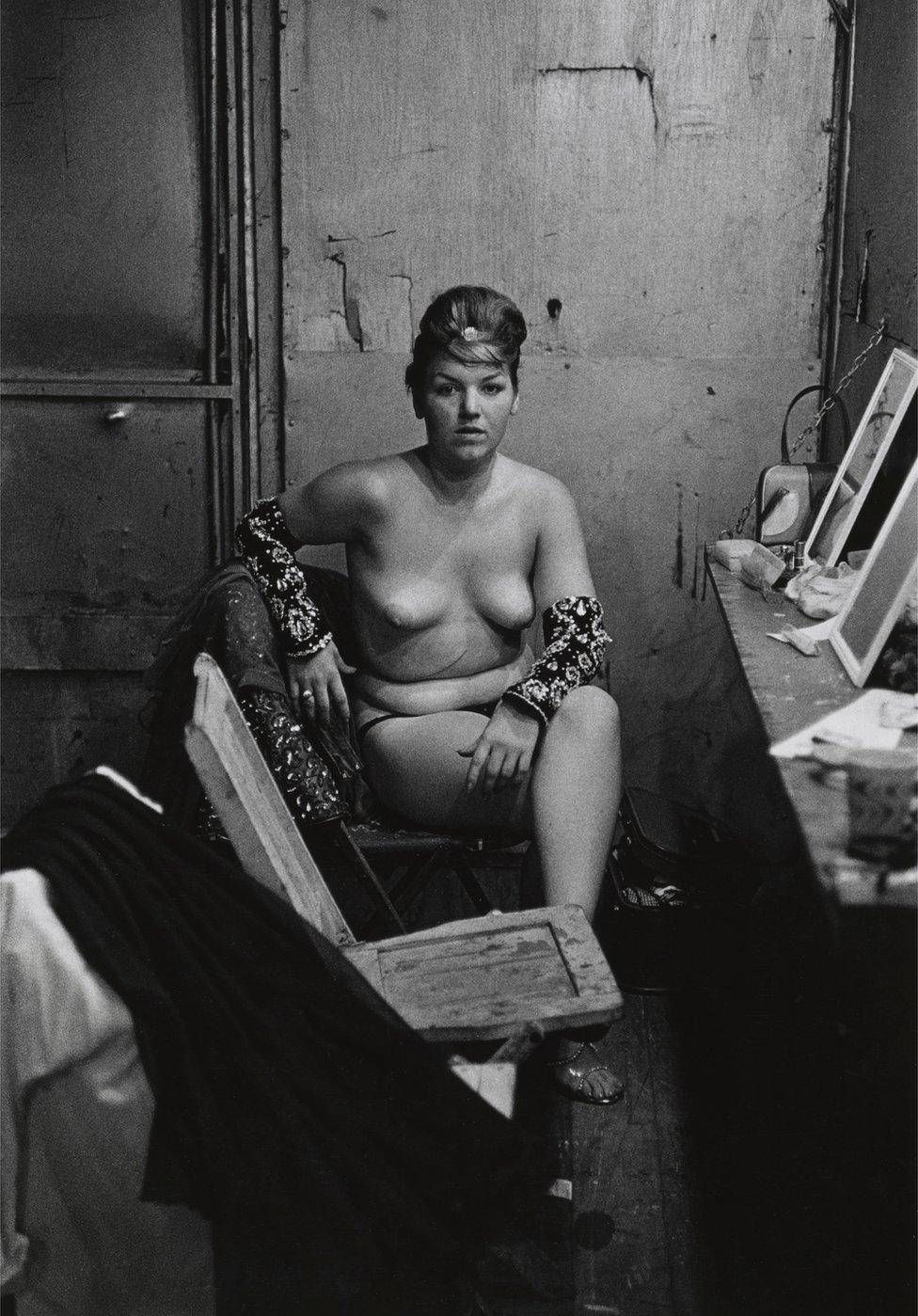

Arbus established a bond with her subjects, before photographing them, as with Stripper with bare breasts sitting in her dressing room, New Jersey, 1961

The more specific she could be, she learnt, the more universal the image.

Inspiration came from an unlikely source.

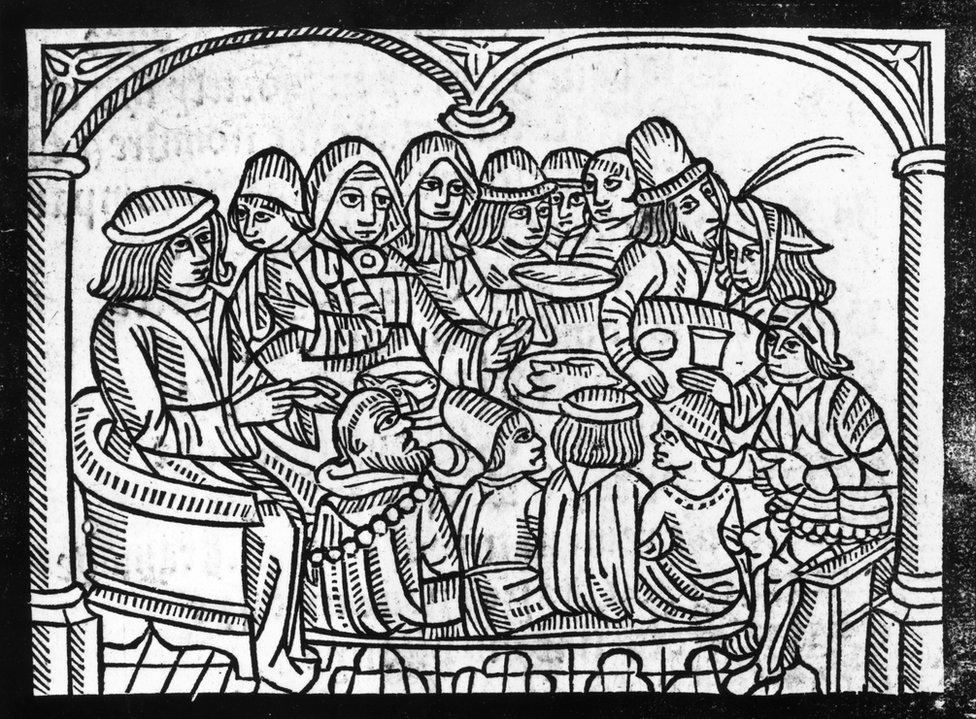

It wasn't another photographer, although she knew and admired many, but sweary Geoffrey Chaucer - the 14th Century Middle English writer. She was particularly taken with The Canterbury Tales, his satirical collection of stories in which a motley bunch of pilgrims travel from London to Canterbury amusing themselves by competing for the title of best storyteller.

Arbus was influenced by Chaucer's The Canterbury Tales and his "tender" portrayal of the pilgrims

Arbus not only admired the range and depth of characters to whom Chaucer gave literary life, but also the "tenderness" with which he treated them. It was a humanity she strove to replicate when photographing the discriminated against, the sort of people from whom most turn away but she looked upon with empathy.

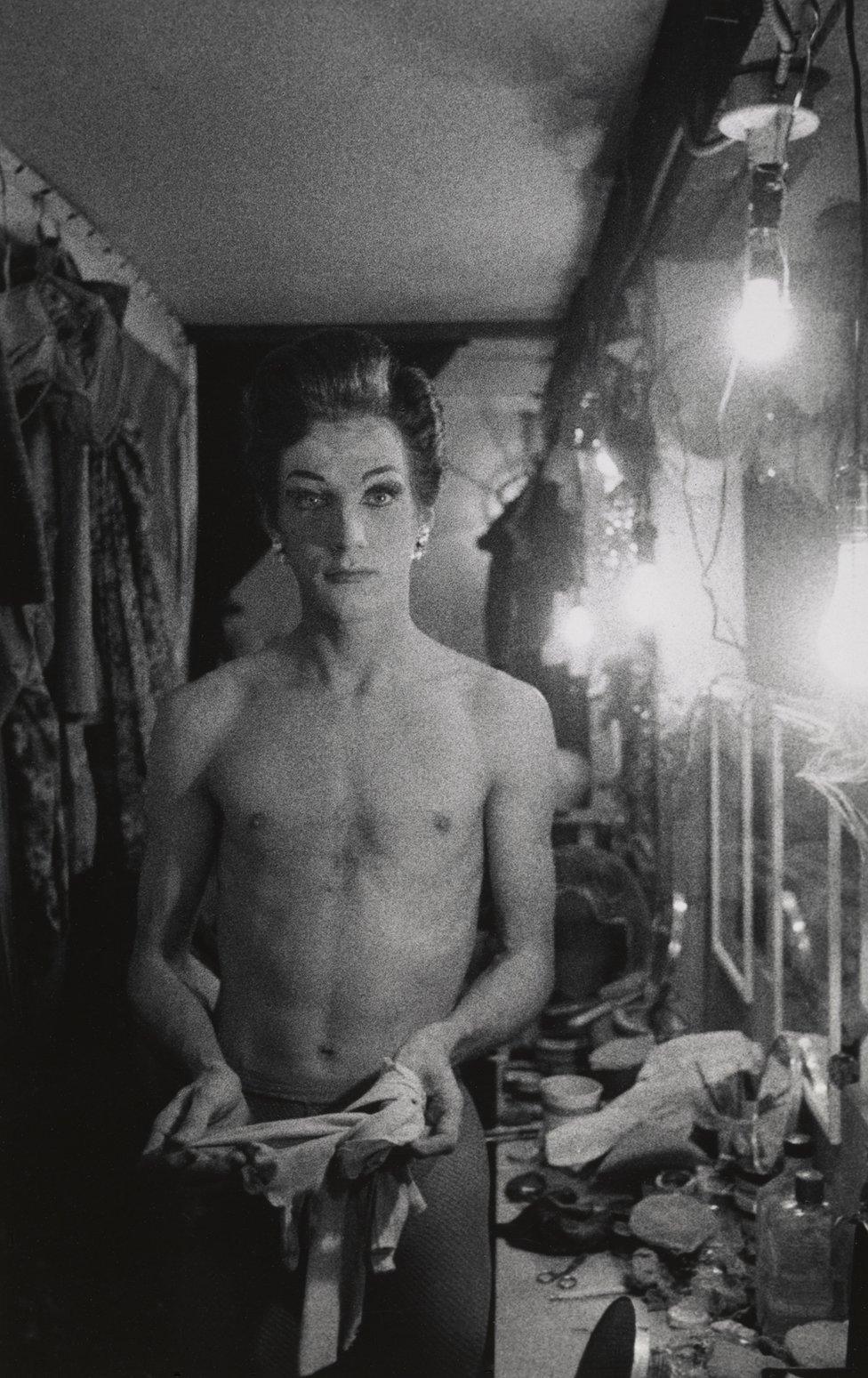

Female impersonator holding long gloves in Long Island, 1959, is an unflinching portrait but full of humanity

"If you scrutinize reality closely enough," she said, "if in some way you really, really get to it, it becomes fantastic."

Freaks, as she called them (a description of the time that has not endured like her pictures), were her muse:

"They were one of the first things I photographed. It had a terrific excitement for me. I adored them. They made me feel a mixture of shame and awe. There's a quality of legend about freaks… Most people go through life dreading they will have a traumatic experience. Freaks were born with their trauma. They have already passed their test in life. They are aristocrats."

As was she - a "department store princess," who grew up in New York on the Upper West Side; the daughter of a wealthy retailer with a huge shop on Fifth Avenue. The fur her father sold was real, but she felt like a fake when walking between the aisles - hence, I suppose, the attraction to oddballs brave enough to be themselves.

Her parents got into art and wanted their 10-year-old daughter to become a painter. Diane was good but found the process annoying.

Eight years later she married Allan Arbus. He gave her that Nikon 35mm camera. It was 1941.

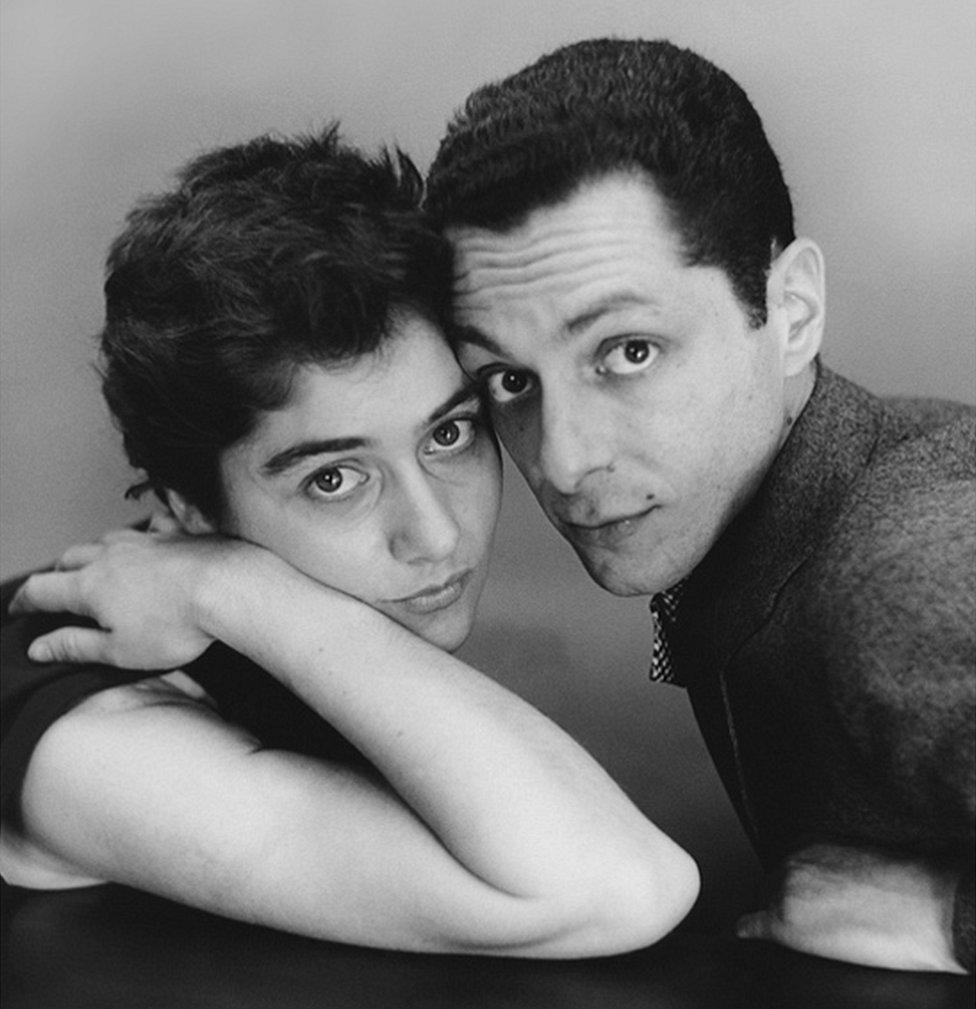

Diane Arbus did fashion shoots with her husband Allan, but wanted to explore worlds other photographers shunned

They set up as a husband-and-wife team producing fashion photos for glossy magazines: Allan took the pictures, Diane was the stylist. Until she grew bored of the role around 1955 and dug out the Nikon.

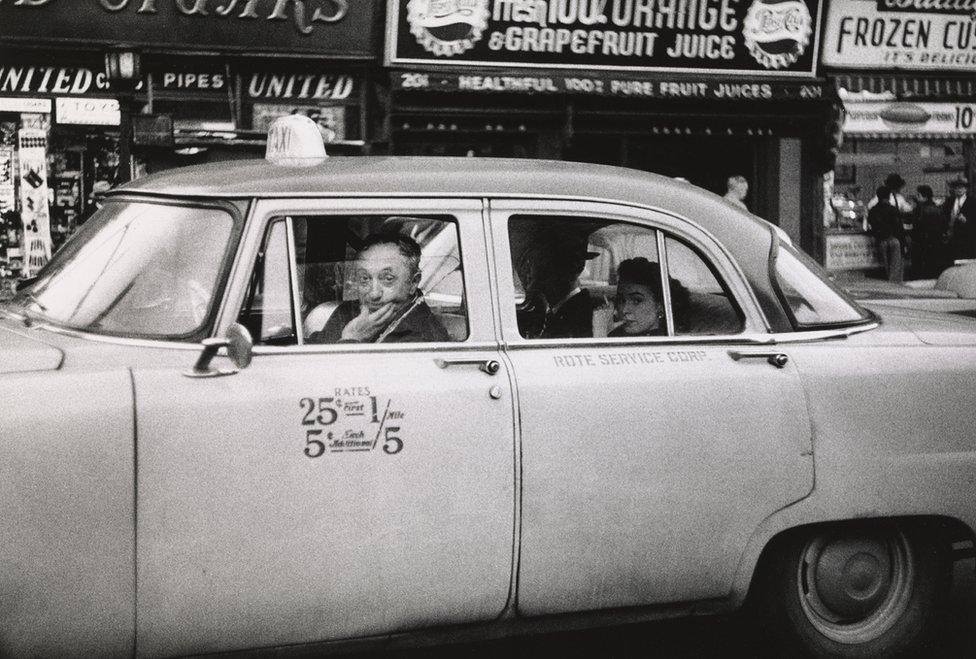

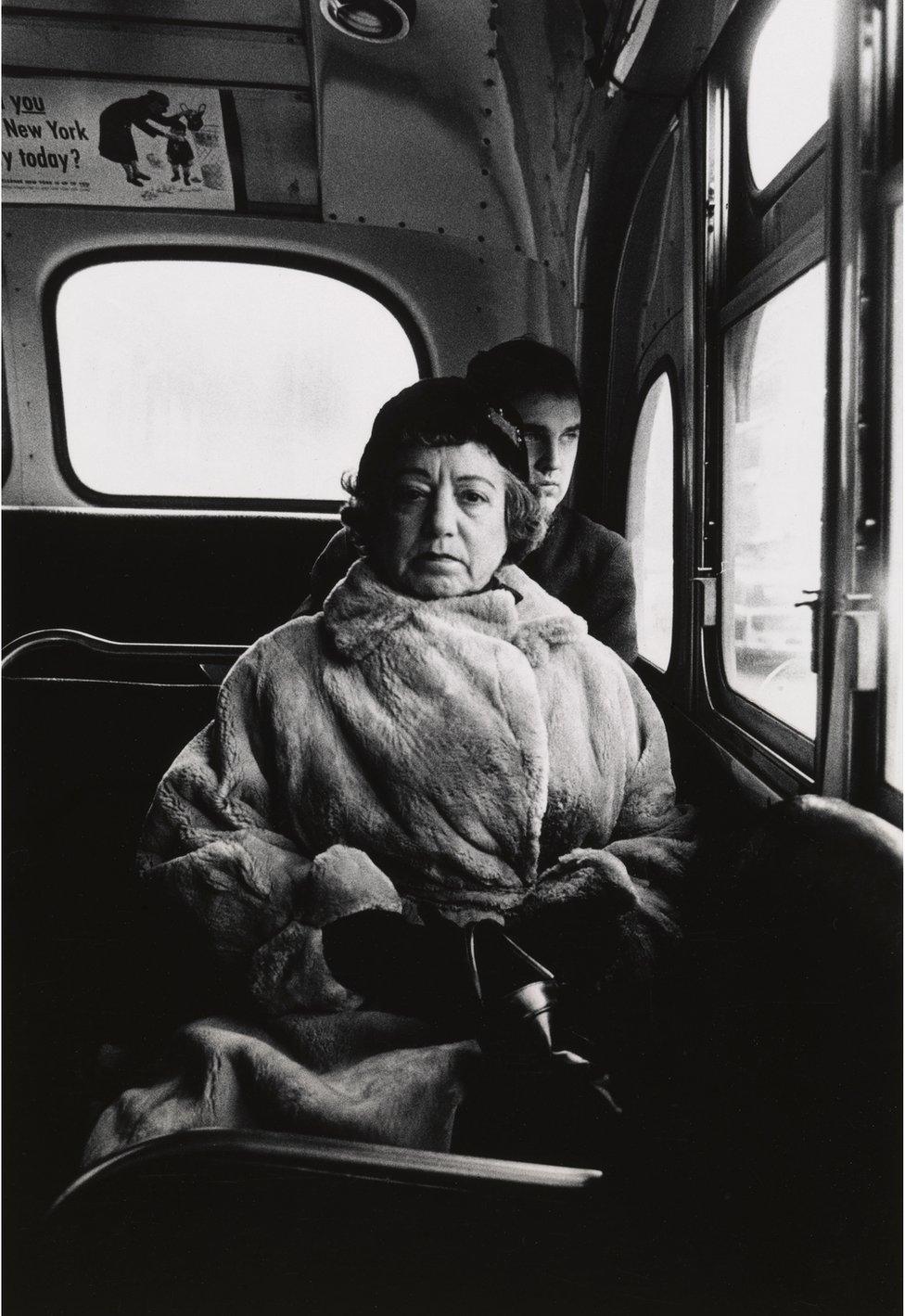

This is where the Hayward Gallery exhibition starts; with the revelation of Arbus's idiosyncratic aesthetic immediately apparent. Images such as Taxicab Driver at the Wheel with Two Passengers, N.Y.C. 1956, and Lady on a Bus N.Y.C. 1957, demonstrate her innate sensibility for composition, contrast, and content.

Every picture she takes is like a single page torn from a novel: a fragment of a story you find yourself reconstructing as you look.

Taxicab driver at the wheel with two passengers, N.Y.C, 1956, shows Arbus's talent for composition

With Lady on a bus, N.Y.C, 1957, Arbus creates an arresting image and story

The Hayward Gallery focuses on her early 35mm pictures taken before she started using a Rolleiflex square format camera in 1962. They are displayed a bit like "Wanted" posters pinned to the trees of New York's Central Park.

You walk among them in a forest of vertical white columns, on either side of which is a black and white figure staring right back at you. It is an effective and affecting presentation.

These are not sentimental photographs.

Nor are they eye candy to entertain and titillate. There is a seriousness about them, a solemnity which can drift toward the surreal and macabre: a moment caught between the vernacular and the uncanny.

The picture of an elderly woman lying on a hospital bed who appears more dead than alive is neither a celebration of life nor a lament for its imminent end. It is something else altogether, more a reflection on the thin invisible line that divides the two for us all.

Arbus doesn't restrict herself to strange folk in order to depict strangeness.

For her it is a fact of life.

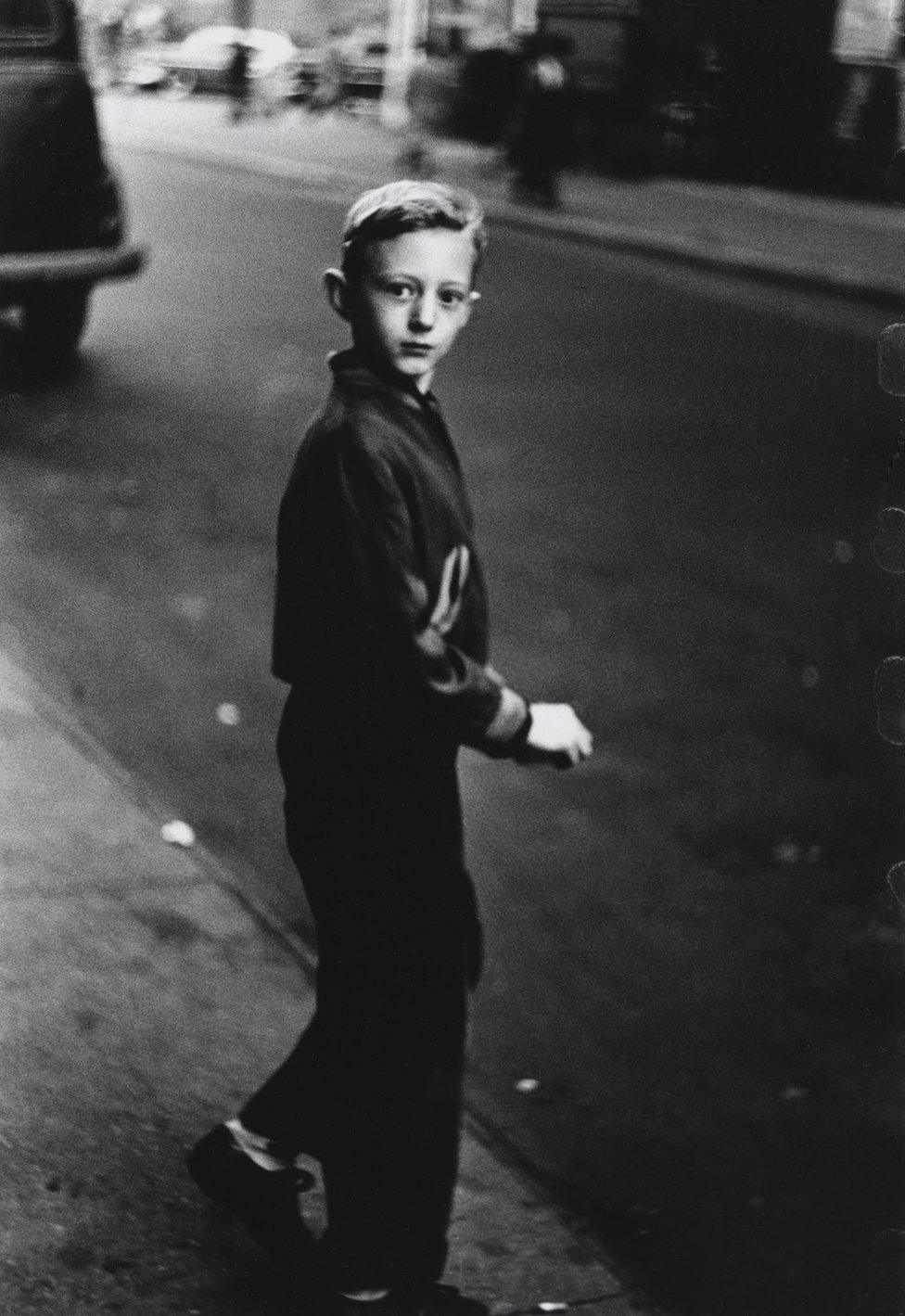

A woman carrying a child, a boy stepping off a kerb - everyday occurrences when isolated and observed become loaded and peculiar.

Boy stepping off the curb, N.Y.C, 1957, captures an everyday action but takes on a loaded meaning

"Everybody has that thing where they need to look one way but they come out looking another way…You see somebody on the street and essentially what you notice about them is the floor. It's just extraordinary."

You can see the occasional flaw in her photographs. Sometimes they feel too staged, her presence too obvious. Others make you question the relationship between photographer and subject: is one taking advantage of the other? A salesman and a sucker, maybe? But which way around?

It is, though, that ambivalence that draws you in.

The more you look the more you see.

Take the photograph of two kids horsing about on the street, for instance. It appears charming at first, but grows darker the longer you spend with it: who is teasing whom and why?

It is just one example of the faintly forbidding atmosphere that pervades the show: an ominousness that comes not just from Arbus's work but also from her life, which she ended abruptly in 1971 by taking her own life, at the age of 48.

Here we see the work of a photographer blessed with great intelligence and a wonderful eye, both of which were aligned to and informed by a curious, troubled mind.

There are a lot of images in this show but no self-portraits. At least, not in the conventional sense. Looked at from another perspective, however, and you can see the sensitive, striving artist that was Diane Arbus in every single one.

- Published16 February 2019