Will Gompertz reviews All the Rembrandts show at the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam ★★★★★

- Published

To look at a vast amount of Rembrandt van Rijn's art in a limited amount of time is like having a blowout meal: your senses tell you they've had enough, you stop, and then after about five minutes you are craving more.

There is simply no other artist like the miller's son from Leiden. Caravaggio was his equal when it came to lighting effects, Rubens matched the virtuosity of his brushwork, but neither of these two Baroque giants could get close to Rembrandt's ability to paint "the passions of the soul".

Go to the astonishingly good All the Rembrandts exhibition at Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam and stand in front of his Self-Portrait as the Apostle Paul (1661) in the first gallery. You will see a picture of a penniless 55-year-old artist who is revealing to you not only what "world weary" looks like, but how utterly dispiriting it feels.

Self-Portrait as the Apostle Paul, 1661 - Rembrandt urges the viewer to engage personally with the Saint

With Self-portrait, c. 1628, the artist comes across as a brash rock star

In stark contrast, on the opposite wall is another Self-Portrait (1628), painted 33 years earlier when the Golden Age master was at the beginning of his career.

It is beyond audacious.

The young tyro stares unsmilingly back at you, as cocky and belligerent as a rock star.

It is a picture of open rebellion in which he blatantly rejects the polite conventions of the Italian Renaissance. He makes no attempt to reach some form of acceptable idealisation. Instead, he reaches for a universal truth by forcing you to look deeply into his eyes by almost entirely obscuring them with heavy shadow.

It is a smart piece of counter-intuitive thinking. By providing you with a measly single beam of light that just catches his right ear, jaw and cheek, he challenges you to come closer to see more. It is an early demonstration of the psychological power Rembrandt can wield over the viewer.

What happens to him between these two self-portraits, both as an artist and as a person, is revealed through the 20 other paintings, 60 drawings and 300 etchings that make up this epic show.

What you quickly learn is his artistic abilities didn't stop with making well-composed, narratively rich, tonally pleasing oil paintings; he was also a phenomenally good draughtsman and printmaker.

Generally speaking, if a grumpy but libidinous man asked you to come up and see his etchings, you would be wise to politely decline his offer. If, however, that wanton misanthrope happened to be Rembrandt, then it would probably be worth the risk.

The images he made by scratching and gauging small sheets of copper in the low-ceilinged second-floor studio of his house, are technically bold and thrilling to behold.

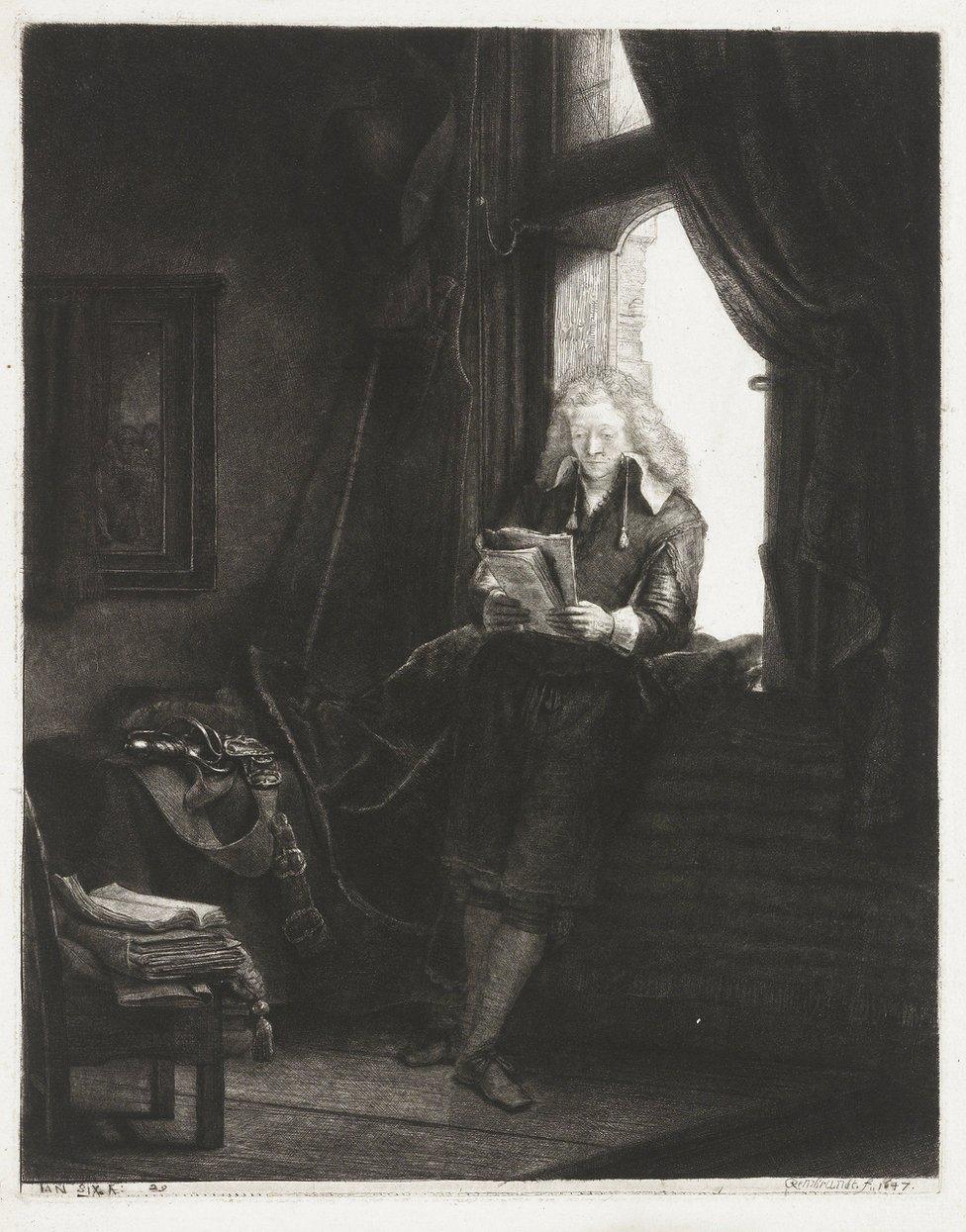

So much so, in fact, that after spending a few minutes looking at his drypoint and burin etching, Portrait of Jan Six (1647), or his drypoint on vellum The Three Crosses (1653), the masterpiece paintings that are dotted about throughout the show start to pale in comparison.

Portrait of Jan Six, 1647, drypoint on paper, reveals the artist's technical mastery

The Three Crosses, 1653, shows the culmination of Rembrandt's virtuosity as a printmaker

Well, not exactly pale, but certainly connect in a different way - the experience of looking at them is less intimate and intense. I suppose it is the difference between watching your favourite band playing a gig in an arena or a room above a pub.

Prior to seeing this exhibition, it might seem hardly credible that when alive Rembrandt was more famous for his prints than he was for his paintings. But after a couple of rooms of seeing them side-by-side you can start to understand how that was the case.

And then there are his drawings.

Unsurprisingly, Rembrandt was a gifted draughtsman. More unexpected is the subject matter he chooses. Along with the typical nude studies and biblical scenes, there are street dwellers (The Pancake Woman c.1635 is particularly good), exotic performers, and unusually private depictions of his wife Saskia.

The Pancake Woman, c. 1635, is "a superb example of the artist's genius for capturing the momentary drama of a street scene with a few strokes of the pen"

She was clearly a great love, that much is obvious from his incredibly touching drawings of her. The great tragedy of his life, the pain you can see in his eyes in all his late self-portraits, is Saskia's death aged 29 when Rembrandt was in his mid-30s and their son, Titus, only eight months old.

I can't think of another artist whose life and work can be so obviously divided into two halves: before Saskia and after Saskia.

Rembrandt and Saskia was a tragic love story of the time; here we see her in Bedroom with Saskia in a Canopy Bed, c. 1638

When she died he was at the apogee of his career. His prints were selling for vast amounts around the world, he had become a pittore famoso (famous painter) among the cognoscenti, and he was living in a splendid house in Amsterdam from which he ran his studio, entertained the wealthy, and bought and sold art.

It was 1642, the year when he completed his most famous work, The Night Watch (not in the exhibition but in another gallery at the Rijksmuseum) and was enjoying married life as a new dad and wealthy member of Holland's elite.

Rembrandt's masterpiece, The Night Watch, will be restored under the world's gaze this summer

When Saskia died everything changed.

Rembrandt was desolate.

He stopped painting, refused commissions, and became "a most temperamental man and despised everyone".

He defaulted on his mortgage, took one lover to court, had an illegitimate child with another who subsequently died of the bubonic plague, and before long had lost his money and reputation. All of which is tragic for him, but not so much for us.

Misery made him an even better painter. With fewer commissions to distract him from developing his ideas and technique, Rembrandt was free to explore the unchartered depths of his talent, feelings and intellect.

His brushstrokes became looser, his painting rougher. The Dutchman's style had always been expressive, but it was tempered, now the brakes came off.

You can see in his late, great painting The Jewish Bride (c.1665) that he is using paint as if it were wet plaster. In some areas the canvas is almost exposed, in others he has applied the paint so thickly with a palette knife as to be almost sculptural. Details have been scratched into the clothes of both lovers who stand in a pyramidal form in a painting as rich with texture as ever you will see.

Vincent Van Gogh is thought to have said he would happily give 10 years of his life if he could sit in front of The Jewish Bride (c.1665) for a fortnight

The harmony of colours and light that unite the two, along with the tenderness with which the hands have been realised, gives the painting an emotional charge that goes way beyond their adoring looks. If ever a painting expressed the emotion of true love, and with it the terrible fear of it being lost, then this is it.

Four years after painting The Jewish Bride, Rembrandt would die.

The exhibition at the Rijksmuseum is a celebration of his life 350 years after his passing.

It is a worthy tribute to a remarkable artist. There is a huge amount to see, but don't rush. Digest it all - and then go back for more.