Will Gompertz reviews Stanley Kubrick: The Exhibition, at London's Design Museum ★★★★★

- Published

Serendipity is the unsung hero of creativity. Any entrepreneur, scientist or artist will testify to that. As will most film-makers.

Luck always has a part to play in the making of a movie, it just never gets a credit.

Stanley Kubrick said as much in an interview back in the spring of 1958 shortly after he'd finished Paths of Glory. He was talking to the actor Jay Varela:

Varela: "Why not begin with how you found the story for the picture."

Kubrick: "The way you find most stories."

Varela: "Well, how is that?"

Kubrick: "Sheer chance."

It was the same deal with A Clockwork Orange, which he only reluctantly read when his wife, an Anthony Burgess fan, pressed him to do so. Thank you, Mrs K.

Malcolm McDowell played the role of the thug Alex in A Clockwork Orange

There is an element of good fortune to the timing of the Design Museum's Stanley Kubrick Exhibition. The show has been travelling the world for a decade or more like a tried-and-tested circus act, but because this year marks the 20th anniversary of the great auteur's death, its London residency feels like a special occasion rather than yet another stop on a never-ending tour.

Still, luck will only you get you so far. Chances have to be taken.

Would the Design Museum, a lively institution that inexplicably does not benefit from statutory public funding, be able to put on a show worthy of Kubrick's remarkable body of work?

The answer is… an emphatic, yes.

The exhibition has been reconfigured and re-thought by the museum's curators with help from the designers, Pentagram. Elements have been thoughtfully added, such as Don McCullin's Vietnam War photographs, which Kubrick used as a reference source for scenes in Full Metal Jacket.

Don McCullin's Vietnam War photographs (Citadel Wall, Hue, 1968) were an invaluable source of research for Full Metal Jacket

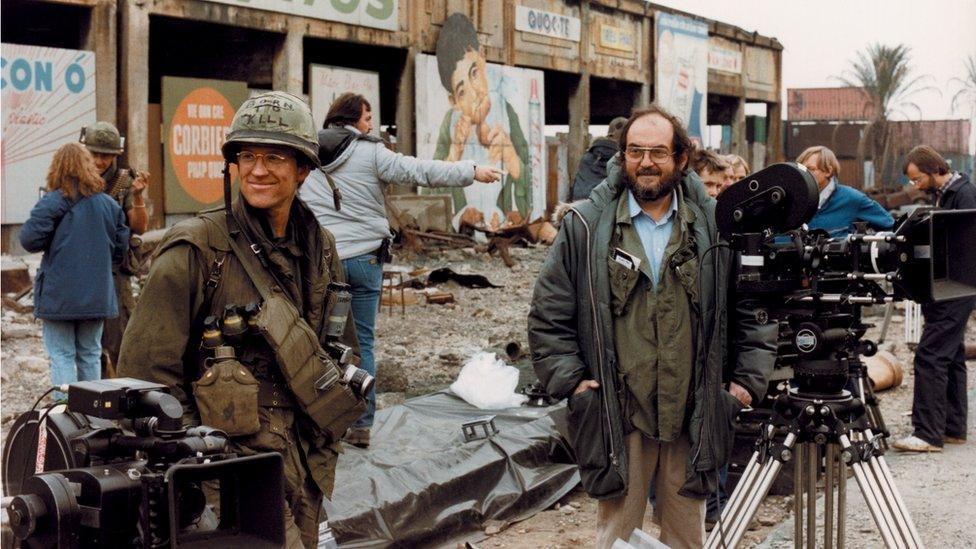

Matthew Modine and Stanley Kubrick on the set of Full Metal Jacket

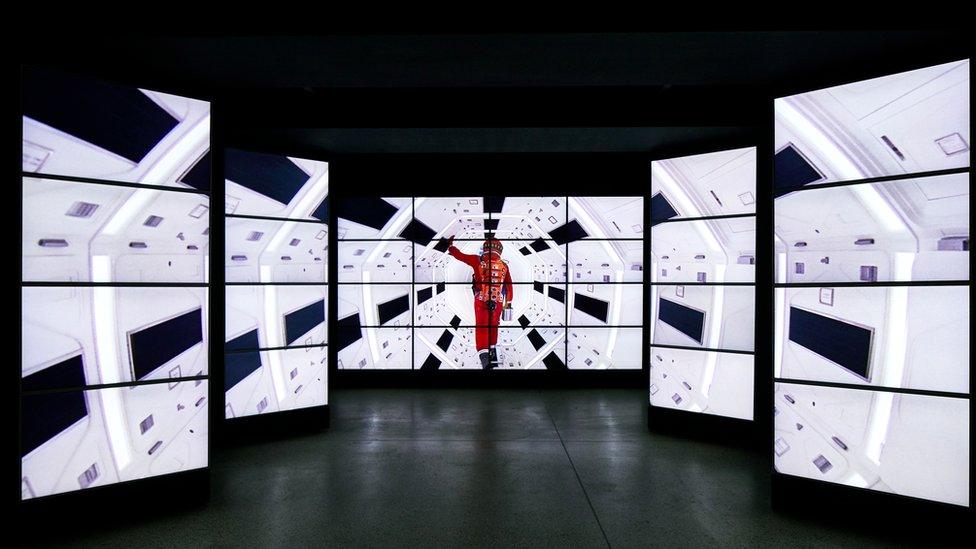

And, with a welcome touch of theatricality, an experiential exhibition entrance has been created consisting of a multi-screen audio-visual display tunnelling towards a central Kubrickian single point of perspective.

You enter the exhibition through a "one-point perspective" corridor, recreating the director's use of the "one-point perspective" technique

It promises - the marketing blurb says - the chance to "Step inside the world of Stanley Kubrick, one of the greatest film-makers of the 20th Century". And you do, sort of. Well, not exactly into his world, more inside his head.

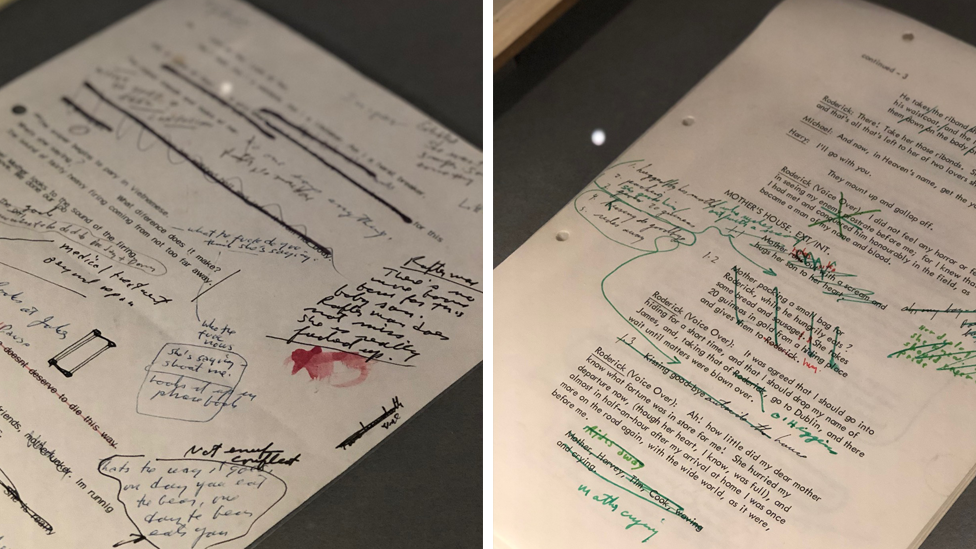

This is far more than a shallow theme-park-type exhibition with a smattering of celebrity objects and archive photographs that you can motor through in a few minutes. Yes, there are plenty of both, but they are contextualised with a wealth of other materials, from annotated scripts and meticulously prepared shooting schedules, to on-set film footage and correspondence with close collaborators.

Kubrick's detailed notes on the scripts for The Shining (L) and Barry Lyndon (R)

You don't really get a true sense of the man behind the camera. Like almost all exhibitions nowadays, this is a myth-making enterprise in which the only criticism of the subject (letters from censors and disapproving cinema-goers) are designed to elevate his status as a maverick genius.

But what it lacks in the way of a serious examination of an idiosyncratic, complex artist, it makes up for with a deeply researched documentary account of his working process.

In the first room, we meet a young Stanley making a living by winning a few dollars playing chess and taking photographs for Look magazine (there's an accompanying exhibition of this early photographic work in the gallery above). We see the Eyemo camera he used for the fight scenes in Killer's Kiss, an early film he considered "amateurish". And in the corner is the cold-metal lumpen shape of his trusty Steenbeck editing table.

Kubrick used this Steenbeck editing machine for Full Metal Jacket

The scene is set.

Kubrick is much more than a director, he is also a writer, producer, cinematographer and editor who saw his job as a "…a kind of idea and taste machine".

What then follows is a room-by-room presentation of all his major films, starting with Paths of Glory and then Spartacus, which has a continuity breakdown sheet on display that reads:

5 Photo Doubles

3,600 Romans

100 Officers

30 Buglers

30 Standard Bearers

2,000 Slaves

This costume was worn by Laurence Olivier (Marcus Licinius Crassus) in Spartacus

Stanley Kubrick didn't do things by halves.

And nor has this exhibition.

If you were to read, watch and look at everything on display, I reckon it'd take you half a day - and that's with an empty gallery. Add a few thousand people and the ensuing queuing, you might have to think about breaking for lunch.

But if you have even the slightest interest in film-making, regardless of your knowledge of Kubrick, this is a show worthy of your time. The exhibits (around 700), installations (including the grand-finale recreation of Space Station V from 2001: A Space Odyssey), and extended film clips are all immaculately and considerately presented.

The recreation of the Space Station from 2001: A Space Odyssey is the star display in the final section of the exhibition

You won't find out what Kubrick was like, but you will discover what it takes to make a great work of art: 99% perspiration, 1% inspiration, and the odd slice of luck.