How The Jeremy Kyle Show became a 'toxic brand'

- Published

Jeremy Kyle had been a fixture on daytime TV since 2005

The decision by ITV to permanently pull The Jeremy Kyle Show after the death of a guest spells the end for a behemoth that dominated daytime schedules for over a decade.

Launched in 2005, its promise to deliver "fiery confrontations" between rowing members of the public, airing their grievances in front of a live studio audience, made it a hit and made its host a household name.

The show quickly became the most popular programme in ITV's daytime schedule, watched by around a million people a day.

Its success was no accident. It was a calculated mix of the benevolence of its UK predecessors (ITV's Trisha and the BBC's Kilroy) and the slapstick vulgarity of the Jerry Springer Show in the US - but with an added sharpness.

Mediator and provocateur

"Jerry Springer was confrontational but had a charm to him that diffused some criticism," remembers TV commentator Cameron Yarde Jnr. "He was as witty but never came across as sneering."

On The Jeremy Kyle Show, meanwhile, the host was "as confrontational as the audience", he says.

Kyle would act as mediator to his guests, being either gentle and kind or, more notoriously, shouting at them to pull their lives together.

"It was popular in a car crash television type of way, but stuck out like a sore thumb in daytime television while programmes around it generally had a more positive vibe," Yarde Jnr says.

The show, and the host's persona, first took shape on the radio.

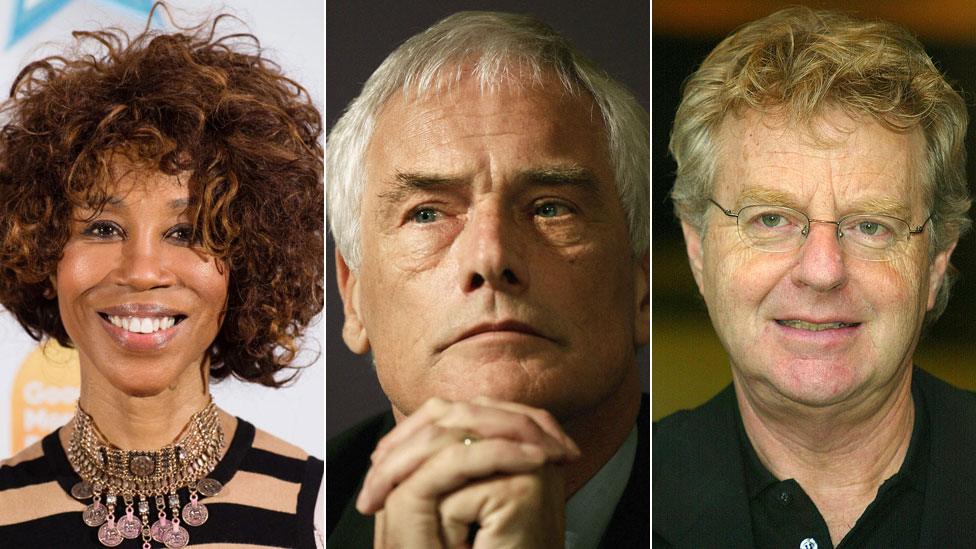

Trisha, Kilroy and The Jerry Springer Show all acted as influences on The Jeremy Kyle Show

Kyle worked in Marks & Spencer and had jobs as an insurance salesman before moving into local radio in the 1990s.

By the turn of the millennium, he had carved out a respectable radio career, hosting his Confessions show on London's Capital FM before taking it to Virgin Radio.

The programme was a precursor to what would later inspire his TV show, allowing listeners to call in with their relationship issues and dilemmas while he listened and offered advice.

The move in front of the camera saw the introduction of DNA and lie detector tests for dramatic effect, with guests clashing over break-ups, child access, addiction and family feuds. When arguments got physical, a bouncer, known as "Security Guard Steve", would break up the fights.

'Raw emotions'

The format relied on an emotional reaction for entertainment value. And this demanded "raw emotions from the guests on the show itself", says Metro.co.uk's deputy editor Alex Hudson.

"The tricky thing is that it required a hero, flawed characters, a villain and a soothsayer. It was almost Shakespearean in that way."

For guests, however, these theatrical roles were their real lives, with a happy ending never assured.

The death of guest Steve Dymond put The Jeremy Kyle Show under intense scrutiny

A former producer on the show, who wishes to remain anonymous, revealed a competitive atmosphere fostered among researchers that encouraged them to "chase" guests and do "whatever they could" to confirm a booking, or risk losing their jobs.

"Researchers would sometimes arrive at 9am and not leave until 6am the next morning unless they'd booked their stories," she says.

The pressure upon researchers to book guests meant it was not uncommon to "play down someone's mental health issues in their filings", she adds.

On the day of filming, guests would be "coached... for hours" about what to say, and encouraged to retaliate against Kyle's retorts, shouting at him as well as fellow participants.

A previous guest told the BBC she found the production staff to be "very pushy and forceful" in telling her what to say, treating her like a "circus monkey".

She said the post-show support, which ex-staffers say included a run of therapy sessions, left her feeling "abandoned" in the long term.

She added that the "shame and embarrassment" of being on the show had been enough to make her move to a different city.

Kyle's controversial moments

I'm sleeping with my stepdaughter but is her baby mine? - a regular on the show admits he is cheating on his partner with her two daughters and may have fathered his step-granddaughter.

Will our relationship survive? - dubbed "envelopegate", Kyle flings an envelope containing the results of a paternity test off stage. After retrieving it and handing it to his male guest, the guest subsequently hurls it at the back of Kyle's head.

Have I been having sex with my brother? - two men in a gay relationship are devastated when a DNA test revealed them to be brothers. The pair met on an internet dating site and spoke for two years before dating. "It makes me sick. It makes me basically horrible," says one.

How could my boyfriend destroy his own face? - Kyle tells a guest sporting an impressively detailed facial skull tattoo: "That's ridiculous, that's the funniest thing I've seen on this show in six years."

In 2007, a judge famously summed up the show, external as "a form of human bear-baiting".

The programme was "trash" that existed to "titillate bored members of the public with nothing better to do", he said. He was speaking while sentencing a guest who had head-butted his love rival during filming.

The show's makers were partly to blame for the attack, he added.

In 2014, media regulator Ofcom upheld a complaint, external relating to the treatment of a 17-year-old girl who appeared on air.

It ruled that Kyle "made comments that clearly reinforced" a negative view of the teenager. At times, his remarks, "rather than limiting her distress, added to it", Ofcom said.

ITV's 'detailed duty of care processes'

The death of guest Steve Dymond, a week after filming an appearance on the show, brought concerns over the real-life consequences of the show's drive for entertainment into full view.

An audience member remarked: "He was put into a position where his story was meant to be entertaining. I'm just shocked by it all."

After the show's initial suspension, ITV said it offered "significant and detailed duty of care processes in place for contributors pre, during and post-show".

A welfare team carried out a "comprehensive assessment" in advance and supported the guests during and after filming, ITV added.

"There have been numerous positive outcomes from this, including people who have resolved complex and long-standing personal problems," a statement said.

The show's eventual cancellation, following widespread condemnation on social media and in the press and an intervention by UK Prime Minister Theresa May, had an "air of inevitability" about it, says Yarde Jnr.

"It felt too toxic as a brand to continue."

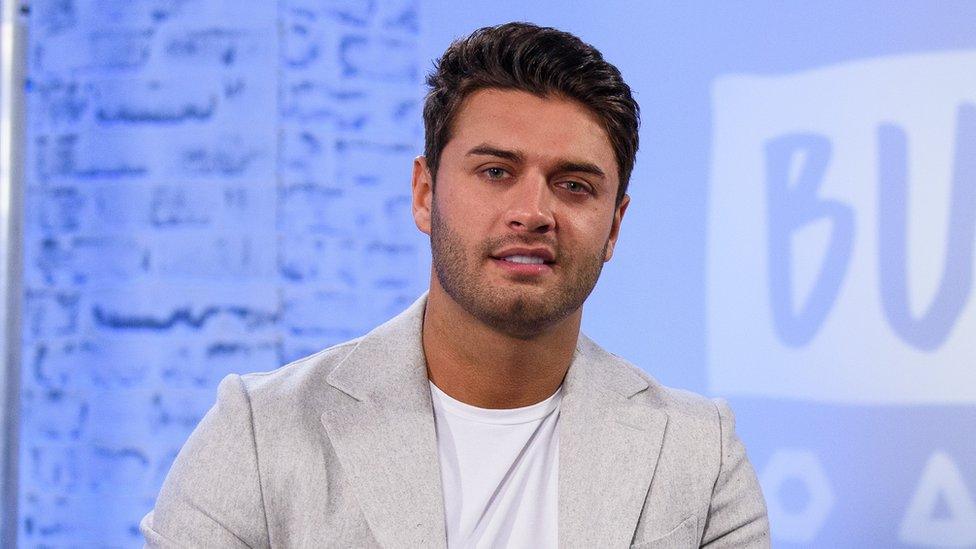

Mike Thalassitis, who took part in Love Island in 2017, died in March

Attention has also turned to the support given to TV show participants across the industry.

ITV had already been under scrutiny following the deaths of former Love Island contestants Mike Thalassitis and Sophie Gradon.

The House of Commons media select committee is to investigate whether TV companies give guests enough support, and media regulator Ofcom is examining whether to update its code of conduct for reality and factual shows.

But The Jeremy Kyle Show's demise won't mean the end of the genre, Alex Hudson believes.

"Audiences will continue to want real-life stories to relate to or be shocked by. The format won't be the exactly the same but key ingredients will be."

He adds: "It hopefully will make TV executives think even harder about the consequences of their programmes on the people who make them entertaining to watch."

Follow us on Facebook, external, on Twitter @BBCNewsEnts, external, or on Instagram at bbcnewsents, external. If you have a story suggestion email entertainment.news@bbc.co.uk.

- Published16 May 2019

- Published15 May 2019

- Published15 May 2019

- Published15 May 2019

- Published15 May 2019

- Published16 May 2019

- Published15 May 2019