Chelsea Flower Show review: Will Gompertz visits the pageant of plants ★★★★☆

- Published

Last weekend the Duchess of Cambridge was splashed all over newspaper front pages swinging on a ball of rope like Miley Cyrus on her infamous wrecking ball, albeit wearing more clothes but with a similar taste in footwear.

She wasn't doing it to sell a song but to promote her "Back to Nature" garden at this year's Chelsea Flower Show, a co-created "woodland wilderness" designed to promote the benefits of an outdoor life for mental and physical wellbeing.

It is a project she has put her heart and soul and back into (17 hours of hard labour according to the man in charge of helping realise her vision).

The Duchess of Cambridge enjoying her Back to Nature garden, which she co-designed

The future Queen is now something of an old hand, whereas I arrived for the press view on Monday as a Chelsea Flower Show virgin. My innocence was clearly obvious. I was barely in and still fumbling my way around when a smartly dressed middle-aged man with an impeccable side parting pulled me aside to tell me all about the birds and the bees.

I thought this was ground I had covered, what with four grown-up children and all, but I was wrong. I had no idea - for example - that shags were under threat, or of the problems associated with the common thrush. But I quickly learnt that both are on the RSPB's Red List of endangered bird species native to Britain.

Although, they were not my man's concern.

Bees were in his bonnet.

He wanted to show me his company's (McQueens Flowers) 20-metre long, spiralling, iridescent, upside-down lavender field-cum-sculpture called Per Oculus Apum (Through the Eyes of Bees), situated in an old concrete tunnel. It was a mighty impressive, multi-sensory ceiling that made for an immersive environment (honey perfume wafted through the air) giving punters a bees-eye view of the world.

McQueens Flowers' lavender sculpture Per Oculus Apum (Through the Eyes of Bees) in a tunnel, has been created to immerse visitors into the sensory world of a bee

It was an evocative installation, but without the star-power of the Duchess's child-friendly, periwinkle-filled playground, which had the added buzz - as if it were needed - of a free limoncello drink (with optional champagne). It was an offer swarms of celebrity guests could not refuse, one of whom described the Chelsea Flower Show as "a wonderful place to be seen".

Maybe the lady in question was planning on coming back as a tree next year. She wouldn't be out of place, performance and art is definitely a recurring theme.

Several of the gardens boasted impromptu shows.

There was a gospel choir banging out numbers in the Morgan Stanley Garden. A topless woman with strategically placed painted roses wandered around unintentionally inconspicuous (who wants to look at fake flowers when you can see and smell the real thing?). And the poet Ian McMillan read a piece he'd written for the Welcome to Yorkshire Garden.

He was good, but the garden was better.

It was designed by Mark Gregory who had taken the concept of a water feature to such an extreme as to makes a Louis VIX fountain seem unimaginative. Into the small patch of land designated to each of the show gardens. Gregory had wedged in: a water-filled, fully-functioning lock, a wild perennial garden (including lupins and stinging nettles), a lock keeper's cottage, a vegetable patch, stone walls and paths, and a variety of trees native to Yorkshire.

Chris Beardshaw's study of fractal geometry inspired his Morgan Stanley Garden, which explores how to manage resources more sensitively

Welcome to Yorkshire Garden, designed by Mark Gregory, features two original canal lock gates, a towpath and a lock keeper's lodge

The Manchester Garden had a flowing, organic sculpture by Liam Hopkins, whose introduction to art and technology was as a young child when he took apart a video recorder having posted a slice of toast into its cassette bay. From little rascals do mighty... carbon fibre objects grow.

Painted white by Hopkins to represent the city's past as "Cottonopolis", he then perforated it with hand-cut shapes to reflect the molecular structure of both cotton and graphene (first isolated in Manchester).

One approach would have been to simply place it as a folly within an urban garden. But the designers wisely chose to integrate it into the fabric of their watery landscape, with flowers and trees growing through its many shapely holes. It's not something you'll be seeing in Tate Modern any time soon, but in the context of The Manchester Garden it worked well as a compositional device.

The Manchester Garden has a sculpture by Liam Hopkins that shows a journey from its past "Cottonopolis" to being the home of graphene

You won't be seeing John Everiss's art down on Bankside either, but that doesn't mean it is not worthy of your attention. The multi-award-winning garden designer's D-Day 75th anniversary installation was a thoughtful tribute to all those who were involved in the Normandy landings in 1944.

15 rectangular stone plinths, each inscribed with the words of a veteran, were placed below the last set of steps leading up to the Royal Hospital Chelsea. All around them was a carpet of 10,000 Armeria maritima plants (often called sea thrift), leading to a life-size stone carving (by Thomas Dagnall) of the recently deceased veteran, Bill Pendell. He looks across the path to an image of his 22-year old self, emerging from the beachhead, appearing in a ghostly form shaped by thousands of welded metal washers.

In John Everiss's moving D-Day 75 Garden is a sculpture of Normandy veteran Bill Pendell looking at himself in 1944

It's not really a garden, nor is it art in a Turner Prize "what's the new idea" sense, but it is a moving monument that has a similar poignance to Paul Cummins' and Tom Piper's field of ceramic poppies.

There is a blurred line between art and garden. Monet said he'd probably never have become an artist if it wasn't for gardens. Georgia O'Keeffe, the American artist, is another who made a garden that would inform her work at her home in Abiquiú, New Mexico, just as Frida Kahlo did in Mexico City. And so did the British sculptor Barbara Hepworth in St Ives, Cornwall.

The Waterlily Pond: Green Harmony, 1899 by Claude Monet, who once said "I perhaps owe it to flowers that I became a painter"

Of all the gardens on show at Chelsea this year, two could be read as either art or design.

Sarah Eberle's The Resilience Garden, which was inspired by the Victorian horticulturist William Robinson, a passionate advocate of the wild garden (another theme running through this year's show), had something of Derek Jarman's famous Dungeness garden. The stony ground, the bald patches suggesting negative space; the faintly bleak atmosphere. Crucially, as with almost all the designs on display, it had something to say, which took it beyond its defined borders and into a relationship with the wider world.

The concept behind the project was to highlight issues brought about by climate change and environmental damage.

Diversity and experimentation are its central arguments.

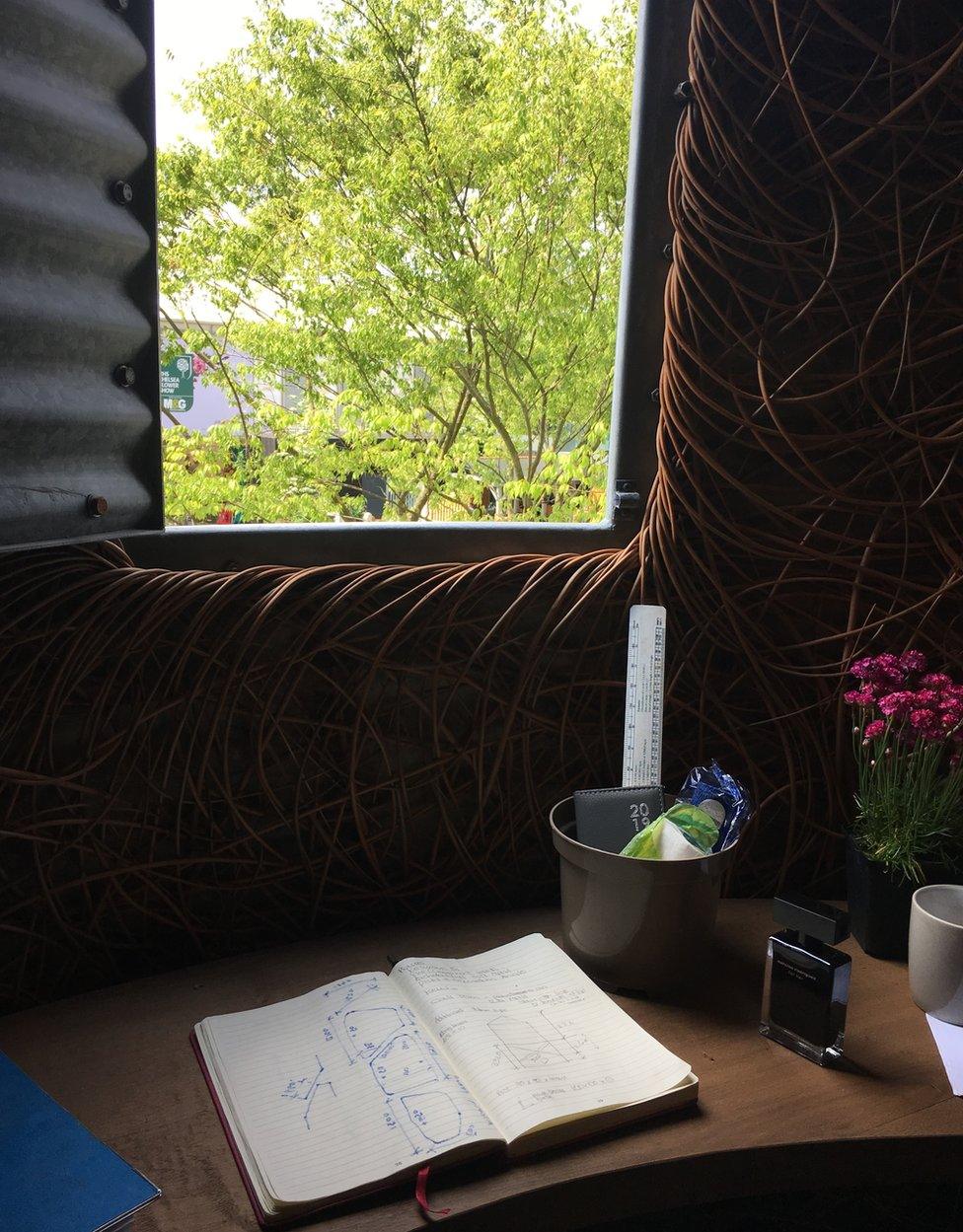

Wildflowers, woodland plants, and prickly pear cacti provide a stage from which hardy trees such as a monkey puzzle and ginkgo rise up to frame a centrally placed old grain silo. Once it was full of seeds, now it is full of ideas: an elevated office in which the designer's notebook lies open on a makeshift desk that sits below a ceiling of weaved willow by sculptor Tom Hare.

Sarah Eberle's Resilience Garden explores the impact of climate change on woodland and wildflowers, and what can be done to make them more resilient

The Resilience Garden reflects a changing world with this raised office under a weaved willow sculpture by Tom Hare

My favourite was the The CAMFED Garden, designed by Jilayne Rickards.

It came about after a research visit to Zimbabwe, and is the result of a subsequent collaboration between the designer and the inspirational local women she met on her trip.

The colours are sensuous, the composition beautifully balanced. At the back, in the classroom, is a painting by a 14-year-old girl of a rural farmyard.

It is exceptional.

The inspirational CAMFED Garden: Giving Girls in Africa a Space to Grow, has been designed by Jilayne Rickards

To see a traditional, tech-enhanced Zimbabwean garden is an unusual sight in central London at what is - in many ways - a traditional, tech-enhanced British garden show.

But it strikes an important note, a reminder of the world in which we all live and rely: a window on to life in another continent in another hemisphere. It is sponsored by CAMFED - the Campaign for Female Education - whose focus is Africa.

But on this occasion it is the well-heeled visitors to SW3 who are the beneficiaries of the organisation's mission to teach.