What's behind the Spice Girls' sound problems?

- Published

The Spice Girls' reunion tour kicked off in Dublin on Friday

If you believe everything you read, the sound at the Spice Girls' recent comeback shows has been zig-ah-zig-awful.

Some fans who attended the opening night in Dublin complained about muffled vocals and being unable to hear the band speaking between songs.

Mel B acknowledged the issues in an Instagram video, saying she hoped "the vocals and the sound will be much, much better" for the second show in Cardiff.

Spoiler alert: They weren't. But by the third date in Manchester, reporters said the sound was "crystal clear, external".

But it's not just the Spice Girls who have suffered from sound issues this week.

The Strokes were beset by problems when they played their first UK show in four years at the All Points East festival in London on Saturday, with one fan comparing the gig to "underwater karaoke".

The audience was filmed chanting "turn it up" during their set, while another festival-goer complained: "If you want to replicate the experience of going to @allpointseastuk put your laptop volume on 50% and stand two rooms away".

Over the last few years, outdoor shows by Eminem, The Killers, Blur and Paul Simon have all been criticised for low volume and poor audibility.

So what's going wrong? We asked some of the industry's leading sound experts.

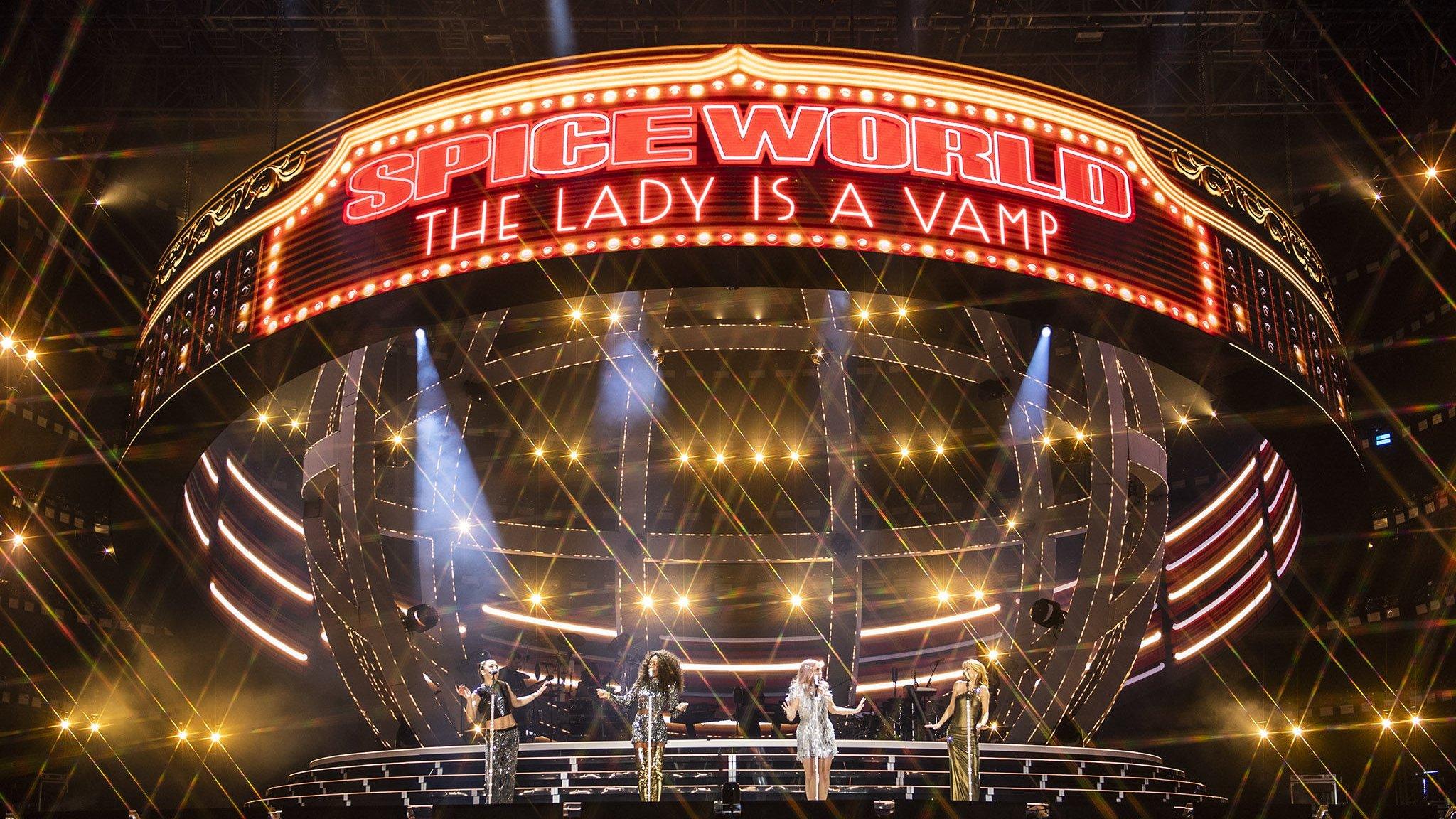

Stage design

The show is designed with catwalks and satellite stages

Sound quality may not have been the top priority for the Spice Girls, says Robb Allan, a veteran sound engineer who mixes concerts for bands like Massive Attack and Radiohead.

"With a huge pop band, quite often the most important thing is the set, it's the lights, it's the video, it's the choreography," he says.

"So even though we design speaker systems by computer - if we can't put our speakers in the right place because of video screens, or because of walkways, or the stage, it makes it harder."

Allan, who's also a live sound specialist for technology company AVID, points out that the Spice Girls have a particular problem because they spend a large proportion of the show on walkways in the middle of the crowd - putting them in front of the speakers.

"And what happens if you have a microphone in front of a speaker? It feeds back. That's just basic physics.

"So that's the challenge in a show like that - the girls are in front of the speakers, they're dancing, they're not giving all of their attention to the singing.

"But it's an old roadie cliché: At the end of the day, nobody goes home humming the lights."

The venues

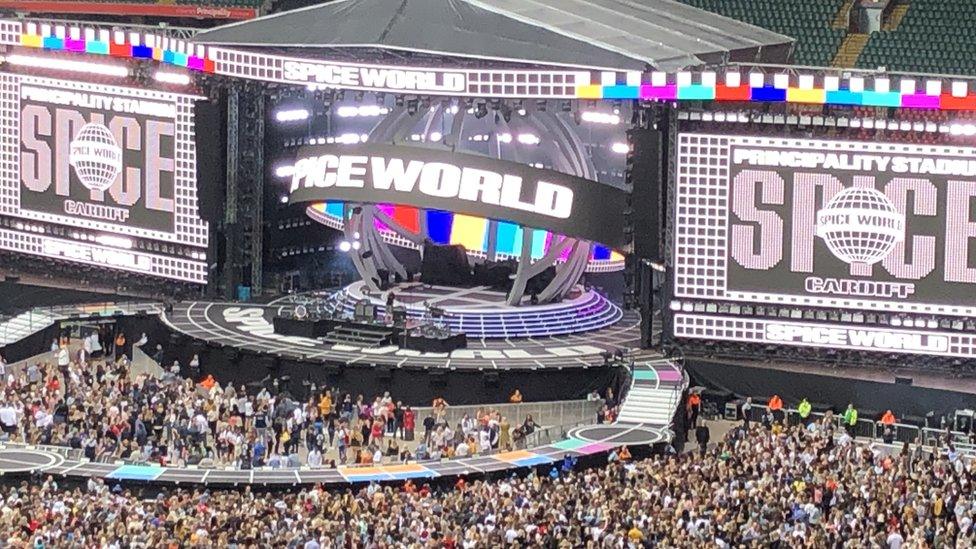

Dublin's Croke Park and Cardiff's Principality Stadium, which were the first two stops on the Spice Girls' tour, "are notoriously horrible for sound", says stage designer Willie Williams, who is best known for his work with U2.

"They're not ideal on many levels, never mind sonically."

The problems with playing music in sports stadiums are well known, agrees Scott Willsallen, an Emmy Award-winning sound designer who has worked on multiple Olympic and Commonwealth Games ceremonies.

"In an auditorium that's built for amplified sound, most of the surfaces are pretty soft and fluffy, so any sound that's fired at them is absorbed; whereas a stadium is meant to reflect those sounds to make it more exciting for the crowd.

"The reverberation that helps make a sporting event really exciting makes a mess of the intelligibility of a concert."

There are ways around it, says Willsallen, who has even gone to the expense of hanging drapes around stadiums to absorb echoes and reverberations.

"It's an exercise that can be done - but in that touring world, where it's such a quick turnaround between venues, I imagine that's a tricky bit of economics."

Crowd noise

Shhhhhhhhh

"Some of the complaints were from people who couldn't hear what the bands were saying between songs," says Robb Allan. "But imagine how much noise 80,000 people make between songs.

"The Spice Girls concert is a reunion, the audience are remembering what it was like to be 18 or whatever, and they're so excited that they talk at the top of their voices.

"And amid all of that racket, in a big old echoey football stadium, the sound engineer's got to take one microphone and amplify it in a way that's louder than those 80,000 people."

Furthermore, many outdoor gigs have volume limits imposed by the local council, which means you can't just turn up the speakers to combat the ambient noise.

"Oftentimes, that noise limit is lower than the noise that can be generated by 50,000 people in a stadium. So there is a hard stop to this," says Allan.

The weather

The Strokes' show was compared to "underwater karaoke" by some fans

Some fans who complained about the Spice Girls and the Strokes noted that their support acts sounded fine. But consider this: as night falls, cool air settles on the surface-level air that's been warmed all day by the sun. Sound tends to "bend" towards the colder air, travelling right over the audience's heads and into the atmosphere.

Outdoor shows are notoriously susceptible to the elements, acknowledges Scott Willsallen.

"Stadiums have their own little micro-climate. Wind, temperature changes, humidity changes - all of them have an effect. It's a minimal effect but still, over a long distance of 100 or 150 metres it can really have an impact on the objective experience for those audience members in the most distant seats."

However, Allan says modern speaker systems - which are distributed across the stadium, rather than being placed at one end of the pitch - have largely eradicated that problem.

"The speaker design is miles from where it was when I started doing this 30 years ago," he says.

"Now we can point the audio into every little corner of the stadium, and predict it with great accuracy. We can change the way the speakers respond to humidity and the temperature. It's all computer-controlled and incredibly sophisticated. So issues are rare."

Heightened expectations

Fans have become used to higher-quality audio since the Spice Girls' first tour

"It's a very unforgiving time because everyone listens to music on earbuds," Willie Williams tells BBC Radio 5 Live. "So they know what this music should sound like. And if you don't get that, it's very disappointing.

"I feel very sorry for [the fans]. It's a horrible situation to be in."

A feedback loop of negative publicity

Allan points out that just 12 people complained about sound issues in Croke Park out of an audience of about 80,000 people. "The whole thing is just a made-up story. It's not real," he says.

"Nobody left, nobody asked for their money back. It's really lazy journalism just to repeat a couple of angry tweets from the back of the stadium and make it front page news.

"That wasn't the experience for most of the people in that concert."

Allan says the "person at the centre of it is a very good friend of mine" who "was distraught, and has no platform to answer the criticisms".

He adds: "I spent the weekend consoling the guy."

Willsallen notes that once sound issues are noticed, its easy for the story to become self-perpetuating.

"People start to expect it to be bad, so they're primed for a bad experience - and they're looking for errors, looking for problems," he says.

However, he believes there is a positive side to the criticism.

"Ten or 15 years ago, the only real way you'd hear about this stuff would be from audience members complaining to the customer service team, or the people selling chips and pies and beer.

"So whilst, as an audio person, I cringe at the thought of people being able to shout about how bad the sound was, at the same time the criticism helps us understand where the problem is and make it better.

"I'm certain that the next shows are only going to improve because people will be asking the right questions to figure out what the root of the problem is and solve that."

Follow us on Facebook, external, on Twitter @BBCNewsEnts, external, or on Instagram at bbcnewsents, external. If you have a story suggestion email entertainment.news@bbc.co.uk, external.

- Published28 May 2019

- Published25 May 2019