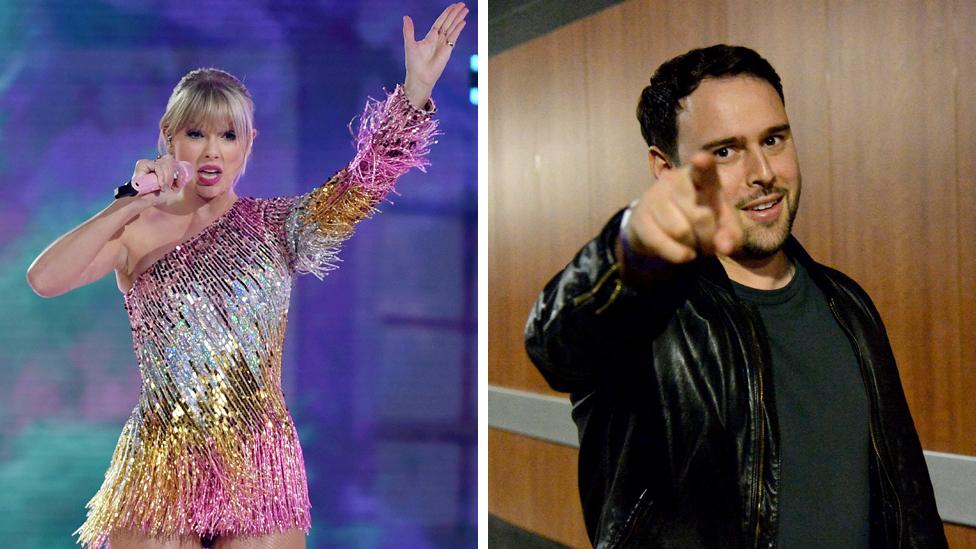

Taylor Swift v Scooter Braun: Is it personal or strictly business?

- Published

Taylor Swift has accused music mogul Scooter Braun of "bullying" and attempting to "dismantle" her "musical legacy" after he bought most of the US pop star's life's work, thanks to his acquisition of her former record label Big Machine for $300m (£237m).

"This is my worst case scenario", she wrote on Tumblr., external

So what is behind the dispute, and how do deals like this work? Let's take a closer look a four key questions.

1) How can someone other than Taylor Swift own her songs in the first place?

When 14-year-old Swift moved to Nashville in 2004 to chase her dream of becoming a country pop star, she signed a record deal with Big Machine.

Label boss Scott Borchetta effectively gave the unproven singer a big cash advance in exchange for having ownership of the master recordings to her first six albums "in perpetuity" - in other words FOREVER.

This was fairly common practice in the days before music streaming and social media changed the industry. Tim Ingham from Music Business Worldwide, external explains: "The idea of a record company signing a new artist today and locking down all of their master recordings to copyrights in perpetuity is far less common.

"Unfortunately for Taylor Swift, she started recording at a time in the history of the industry when it was still heavily reliant on radio, where you needed a record company backing to get you on radio, particularly country radio in Nashville, where Big Machine was a huge player. And also, you needed to rely on physical distribution to get your CDs into stores. So she needed a record company to invest the amount of money that they had to invest to get her career off the ground."

Allow YouTube content?

This article contains content provided by Google YouTube. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read Google’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

2) Why couldn't Swift buy back the rights to her own songs once she got rich and famous?

It seems she could've done - but this is where things get a bit murky.

Swift says she unsuccessfully "pleaded for a chance to own my work" for years. But Borchetta disputes those claims, saying she "had every chance in the world" to own her music, and that "she chose to leave".

Ingham believes Swift could have afforded to buy back the rights. "She could have potentially raised some money, bought the label and then sold off the other masters, perhaps back to the artists [on the label] - or started her own label," he says.

But the singer says the only opportunity she was offered to regain the rights was by signing another deal with Big Machine and "earning" one album back for every new one she produced. "I walked away because I knew once I signed that contract, Scott Borchetta would sell the label, thereby selling me and my future," she says.

To add further spice to the story, the 29-year-old's father is believed to own approximately 4% of Big Machine, a fact not lost on Braun's wife Yael Cohen Braun, external. Some quick maths suggests Swift senior is in for around $12m of the Scooter Braun deal.

"Although she might be very personally upset about it," says Ingham, "her father just had a an eight-figure sum added to his bank."

Swift's new deal with Universal's Republic Records label - beginning with her seventh album Lover, which is released in August - is not likely to be anywhere near as onerous.

3) Is it personal between Swift and Braun? Or strictly business?

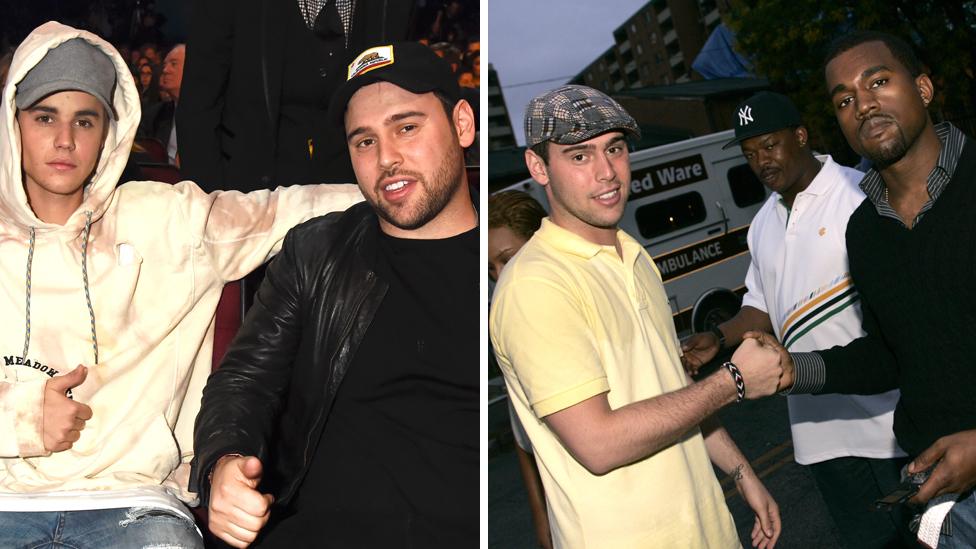

Aside from now owning Swift's back catalogue, Braun also manages Ariana Grande and Justin Bieber. Following the Bad Blood singer's allegations of bullying, the Canadian star leapt to his boss' defence, writing on Instagram, external that Swift was just out "to get sympathy".

Also in Braun's talent stable is Swift's old nemesis Kanye West, and a theory from her fans - aka the Swifties - online is that Braun bought the rights simply to spite her for the feud that began when West stormed the stage when she accepted an award at the 2009 MTV VMAs.

For Ingham this argument simply does not add up. "People do not spend $300m venture capital money with their primary motivation being that they just want to pee off a superstar," he says.

Kanye West interrupting Taylor Swift at the 2009 MTV VMA's

Bieber and Braun, and a much younger Braun with West

Mark Sutherland, editor of trade publication Music Week, external, agrees that Braun's bottom line would surely be the bottom line.

"All her albums have been phenomenally high-selling - some of the biggest-selling albums in recent pop history," he says. "A lot of those songs are going to be a small goldmine in the streaming environment as they are enduring pop hits that are going to be streamed from now until the next 20, 30, 40 years."

He adds: "A one-off hit doesn't raise as much instant cash as it used to, but a hit that's still being streamed decades into the future is going to pay for itself over and over and over again."

Braun hasn't responded to requests for comment.

4) Has a high-profile music rights case become so bad-tempered in public before?

Sir Paul McCartney and Michael Jackson

For Michael Jackson, when it came to The Beatles, you simply couldn't Beat It. So much so that he bought the publishing rights to their back catalogue back in 1985, but nobody knew about it until years later.

These days, very little remains private any more. "A few years ago, none of this Taylor Swift story would've played out in public," says Sutherland.

"There would've been some legal letters flying around in the background and we'd probably have never heard of it. Obviously the rise of social media gives artists a much bigger platform than they've had before - and the executives maybe as well. I think it's much easier these days to weigh in in public.

"Things that would once have been confined to legal offices are now much more out in the open. Borchetta's published some of the details, external of their negations and I don't think you'd have seen that even a few years ago."

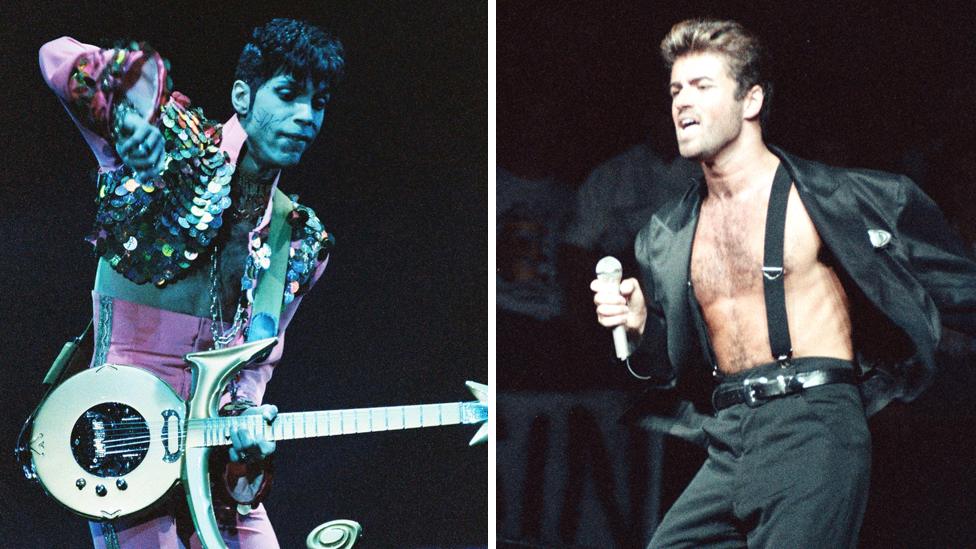

Prince and George Michael

Ingham points to two other artists, Prince and George Michael, as examples of those who have taken on their record companies in the courts, to varying degrees of success. He suggests that had they had legions of online fans in those days, then the rich and famous singers might have got a fairer deal in the press.

"You might remember that very famous image of Prince with 'slave' written on his cheek," he recalls. "The tabloids had a field day with that and there was almost zero sympathy for the artist. Now with social media, you get the undiluted un-spun message from the artists - they don't need the mass media to get their message and their frustrations across.

"So if all of those millions of Swifties around the world are hearing direct from Taylor that this is an upsetting and unfair turn of events, then they're going to tend to believe the person whose poster they have on their wall as opposed to the multi-millionaire businessman."

Follow us on Facebook, external, on Twitter @BBCNewsEnts, external, or on Instagram at bbcnewsents, external. If you have a story suggestion email entertainment.news@bbc.co.uk, external.

- Published1 July 2019

- Published27 August 2017