The 'sort of impossible' challenge of bringing Life of Pi to life

- Published

Life of Pi tells the story of a boy stuck on a lifeboat with a tiger

A Bengal tiger growls menacingly as it prowls the rehearsal room. A zebra, hyena and orangutan are also on the loose. And a 16-year-old boy is doing his best to stay out of the way of them all.

The tiger is about to pounce, but the despairing boy distracts it by catching a rat and throwing it in the predator's direction.

He's safe. For now.

There's no particular panic among the other couple of dozen people in the room, though. Well, only the low-level panic you get when you're turning one of the best-loved and best-selling novels of the past two decades into a major play, and opening night is approaching.

The tiger growls again. The boy throws the rat again. And again.

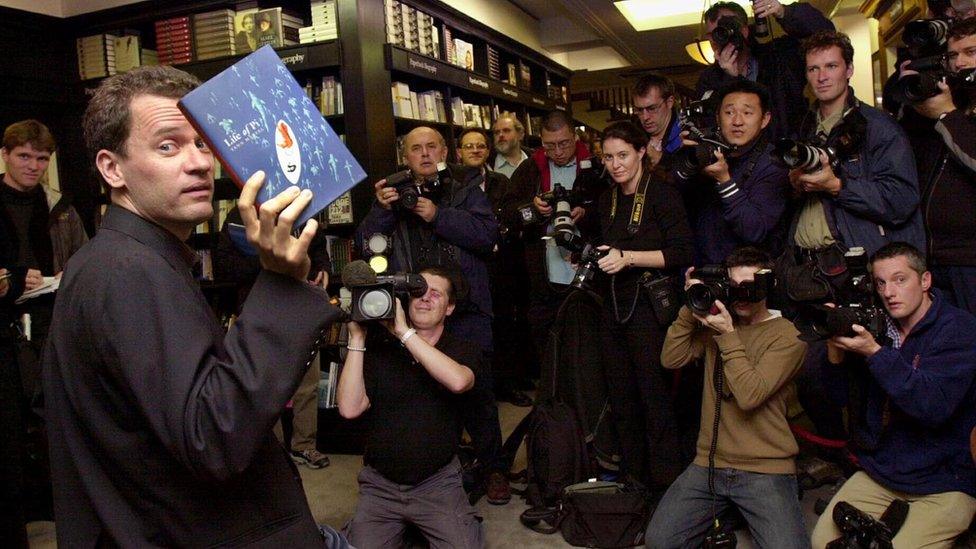

The novel is Yann Martel's Life of Pi, which tells the story of an Indian boy who is stranded on a lifeboat with a tiger in the middle of the Pacific Ocean. It won the Booker Prize in 2002 and has sold more than 15 million copies.

The book became a big hit after Yann Martel won the Booker Prize in 2002

For the rehearsals, one floor of an empty department store in the middle of Sheffield is doubling as the Pacific Ocean - there isn't enough space in the usual rehearsal room at the city's Crucible theatre, where the show is being staged.

The animals are puppets, but even though the tiger needs three people to operate it, it still appears disconcertingly realistic, especially when it is growling in your direction.

Life of Pi is an enchanting book about survival and religion and what is real and what's not. But for a long stretch, it is just a boy and a tiger. In a lifeboat. At sea.

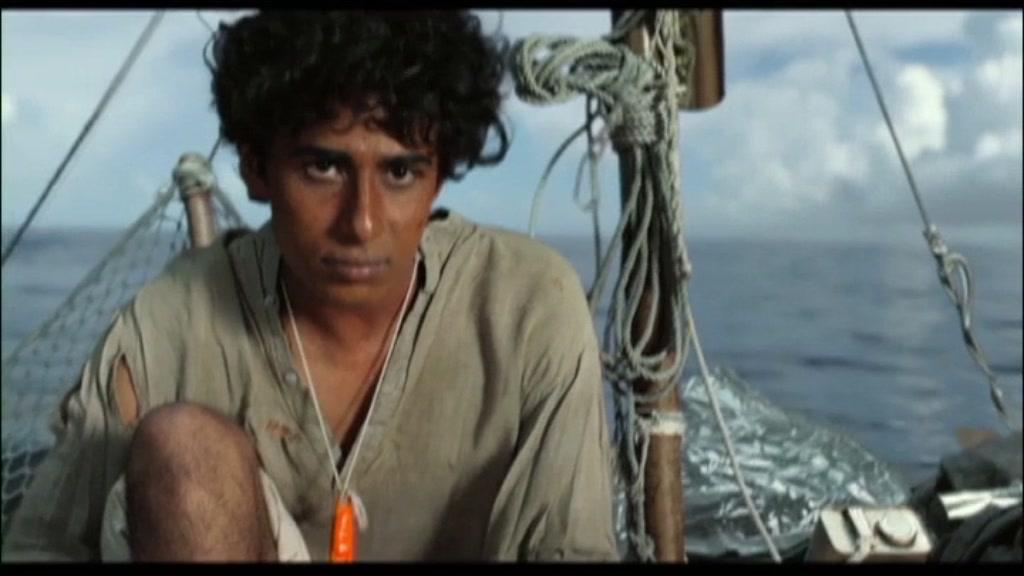

When it was adapted for a film by director Ang Lee in 2012, people wondered how it would work. But Hollywood has the benefit of CGI wizardry, and it ended up winning four Oscars, including best director and visual effects.

So how on earth will it work in a theatre?

Lolita Chakrabarti has adapted the novel for the stage

"Loads of people said to me, 'Oh, my God, how are you going to do that?'" says writer Lolita Chakrabarti, who has adapted the book for the stage. "I was like, 'It's just theatre!' And as it's gone on, and I've seen what an enormous story it is, and how theatrically challenging it is, I've got more and more daunted."

Martel says he has been more involved in this theatre version than he was in the film. "If anything, I think theatre will work better telling the story than the cinema," he argues. "The problem with cinema is special effects are so developed that they can imitate any kind of invented reality they want, and we're used to it now.

"Now you have stupendous special effects that cost thousands of millions of dollars, and we just sort of shrug it off. What's wonderful about theatre is that the artifice is so visible. You can see obviously it's a puppet. It's a dorky puppet. But it moves so naturally."

People are asked to use their imaginations and so buy into the magic of a tiger coming to life on stage, he says. "Whereas in the movies, you realise it's just a whole bunch of computers and it seems sweatless and artificial, and you don't buy into it emotionally."

The tiger requires three humans to operate it

The animals, fashioned from a lightweight, super-strong foam, are being overseen by puppetry director Finn Caldwell, who was in the original War Horse cast and has helped pioneer the use of puppets on stage. Life of Pi is full of "sort-of-impossible staging challenges", he says.

Some of the actors operating the animals have had lots of experience with puppets, while others have had none. In preparation, they studied videos and read about how tigers, hyenas, zebras and orangutans act, and have tried to imagine what might happen when they get together in a confined space. "That level of puppetry choreography is further than I think I've ever done," Caldwell says.

As well as the puppets, the show will use state-of-the-art projections on the stage and backdrop to conjure up an entire Indian zoo, and then swiftly summon up the vast, mighty Pacific.

"Sometimes big physical theatre shows are about the tricks themselves, or showing off about spectacle and images, which can be amazing and beautiful," says director Max Webster. "But this is very much taking all these theatrical techniques to serve a great human, serious, emotional story. It's not just about a magic zebra - it's got a big human point to it."

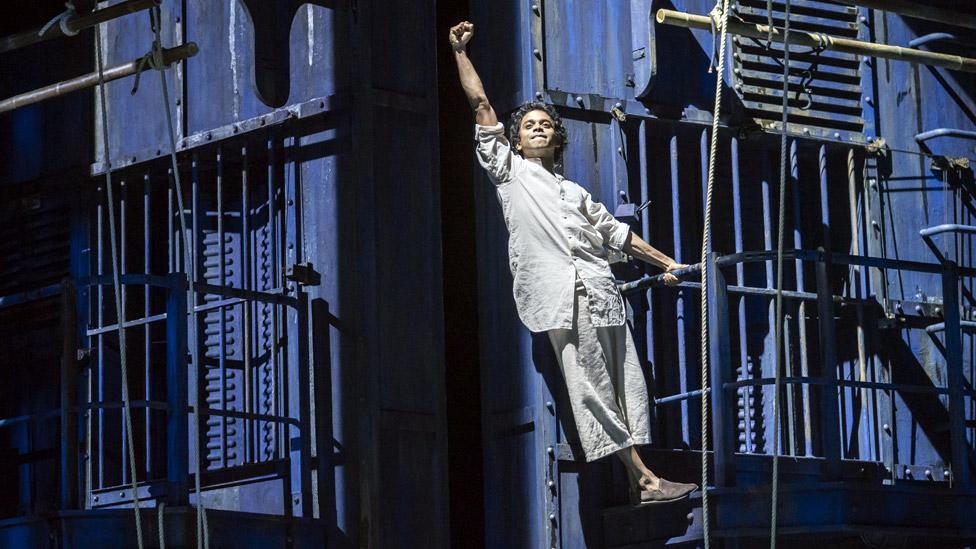

Pi is played by Sri Lankan actor Hiran Abeysekera

To help bring the human story to life, Chakrabarti has decided to make 16-year-old Pi, played by Hiran Abeysekera, see visions of his family and other characters as he is helplessly swept across the sea with only the tiger for company.

"If you go through a terrible time in any walk of life, the things that get you through are what you've been taught, and the echoes of people in your life," the playwright says. "So ghosts - elements of people that taught him things and who were significant to him - appear in the middle of the Pacific Ocean, and he has a conversation with them, and they help him solve how to eat, how to find water, how to kill a turtle and eat it."

This is the first major stage version of Life of Pi, although it has been attempted once before, by now-defunct theatre-in-education company Twisting Yarn, in Bradford in 2004.

"Just before we signed on with Hollywood, they snuck in," Martel says. "In fact, there had to be huge negotiations between the Goliaths of Hollywood and these little Davids in Bradford to negotiate to allow it, because I'd already committed to them before we'd signed the contract with Hollywood. And Hollywood, when they buy film rights, they get 'all rights in the Universe'. That's the actual language they use."

Twisting Yarn had a tiny budget for their version. "And yet simple stories, reliance on words, great acting and very simple effects - it was very powerful," Martel adds. "So I did have a glimmer of what theatre can do."

Life of Pi is at Sheffield Crucible until 20 July.

Follow us on Facebook, external, on Twitter @BBCNewsEnts, external, or on Instagram at bbcnewsents, external. If you have a story suggestion email entertainment.news@bbc.co.uk, external.

- Published8 February 2013

- Published21 November 2012

- Published2 February 2011