Glastonbury: The last person bands see before playing the Pyramid Stage

- Published

Tony Szymkow built the Pyramid Stage - then helped manage it with his wife, Jo, for 36 years

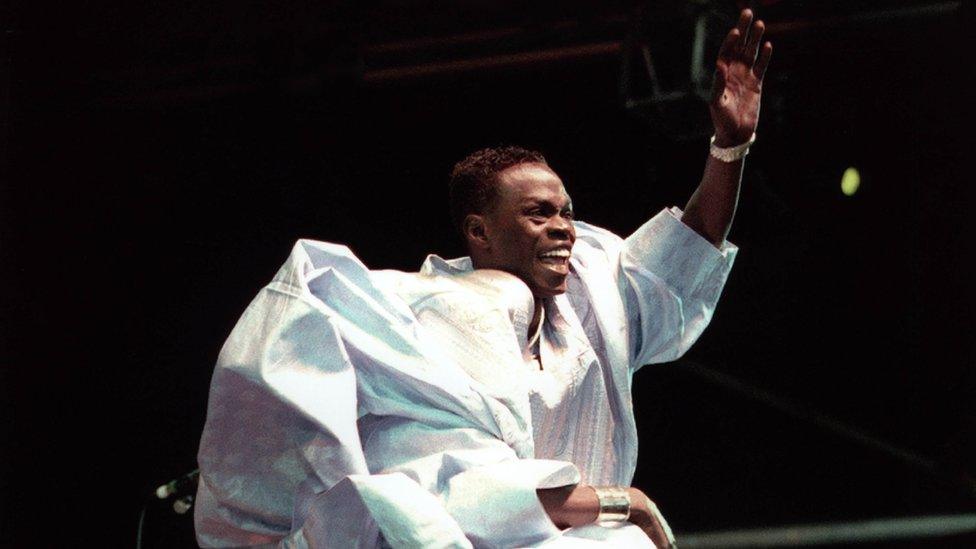

In 1993, Senegalese musician Baaba Maal was kicking around a football with his band to pass the time before he played Glastonbury's Pyramid Stage.

Suddenly, a mistimed volley smacked him in the head, and he collapsed to the floor, clutching the side of his mouth.

Slowly, but surely, his face started to swell up. It was clear he was in incredible pain. So dressing room manager Tony Szymkow got on his radio and called for the on-site dentist.

"She came down with a box of what looked like torture implements," he recalls.

"But the power went off, so I ended up holding two torches to illuminate the inside of his mouth, while she investigated.

"Suddenly she said, 'This isn't going to be pleasant'. I thought she was talking to him, but when she burst the abscess open the smell was unbelievable. Baaba was groaning while she mopped it up and put clove oil on it; and I nearly fell over with the smell.

"And then," he recalls, "I had to march him on the stage to do the gig.

"And he was fantastic."

Baaba Maal went on to play his set without any hint of the backstage emergency

It's no exaggeration to say Tony Szymkow has seen a lifetime's worth of eye-opening moments in his 36 years behind the scenes of the Pyramid Stage.

He's the one that had to knock on David Bowie's dressing room door with a two-minute warning. He's the one who had to persuade bands off their tour buses in the pouring rain. And he's the one who had to turn away "several A-listers" every year, "including one of your BBC colleagues, who was quite insistent". (He names no names).

Szymkow started working at Glastonbury in 1981, when he was contracted to build the Pyramid Stage.

"The frame was made out of wood and blast-proof steel that Michael [Eavis] had bought from the Ministry of Defence, which is ironic, considering that it's a CND festival," he says.

The build was so complex, that the stage wasn't finished in time for the festival - and Szymkow recalls hauling the apex of the Pyramid to the top of the structure and fastening it in place as the opening speaker, historian Sir George Trevelyan, was addressing the crowd.

"Then we climbed down, pushed the Thompson Twins' gear out to the front, and the show started."

That was supposed to be the end of Szymkow's involvement - but Eavis gathered the crew up and assigned them all jobs as stage hands. Szymkow was to be the drum roadie, because he played drums in a band at the time.

"Michael is very charismatic, and we just didn't question it. We stuck in and did it."

And he never left.

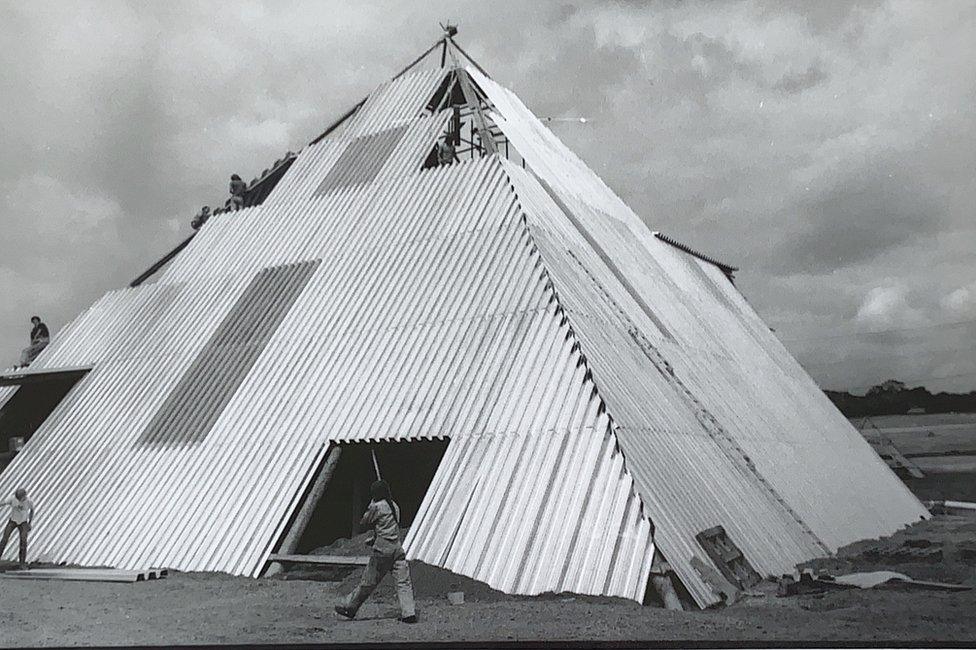

The Pyramid Stage under construction in 1981

Tony says the stage was built with telegraph poles and scrap metal

The stage burned down in 1994, just weeks before the festival. The new structure is in place all year round

Since 1981, Szymkow has seen the festival grow from a single-stage event, with 17,000 hippie-fied ticketholders, to the sprawling, internationally famous event we know today.

"It was pretty out there in '81, '82 and the early days," he says.

"But in the 90s, when Britpop started happening, you started noticing the audience was no longer on the hippie end of the spectrum.

"It did get a bit difficult before the big wall went up," he adds, referencing the £1m fence was erected in 2002 to keep out gatecrashers.

"We had an awful lot of people here, some of whom weren't very nice. But it's evolved and improved. I think it's still quite close to the original intent."

Affable and unflappable, Szymkow is instantly trustworthy - while making it abundantly clear he operates a strict no-nonsense policy.

It's the perfect demeanour for someone who has to keep the competing demands and egos of the Pyramid Stage's backstage area in check.

He recalls one band who, upon being told their stage time was imminent, demanded "five stretchers and 10 strong men".

"I said, 'Why? What's happened?' and the guy said, 'We don't do mud. We've got winkle pickers and stage clothes, and we need to be carried over'.

"And I said, 'OK, I'll give you black bin bags to put over your shoes' and they walked across the car park like the saddest sack race you've ever seen."

Lou Reed's odyssey

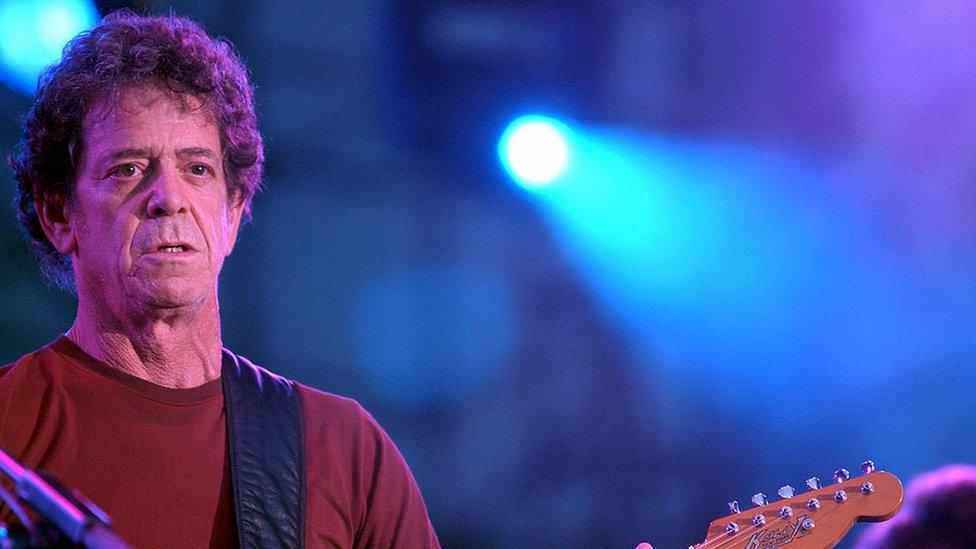

But he'd rather dwell on the happy memories - like the time he stood next to REM's Michael Stipe as they watched Radiohead, with Stipe singing every word, or the night Lou Reed stuck for an extra day after his show, sharing beers with the crew around a campfire.

Yes, that Lou Reed. The famously irascible and disagreeable musician, who reduced several interviewers to tears.

"Lots of these people are notoriously grumpy and I think it's their entourage that's trying to keep them away from reality. I've also toured with Prince and he was perfectly ok on a personal level."

Lou Reed: Not as grumpy as he looks

After hanging out with the crew, Reed had to work out how to get back to London.

"The production manager said, 'Would you be OK going home on the train?'" recalls Szymkow, "And he said, 'I'd be OK with the train.'

"Our friend Stephanie, a life-long Lou Reed fan, took him to Castle Cary train station. But he didn't want to get out of the car, because the station was full of punters leaving, so he got back in with Stephanie and they just chatted and smoked a cigar.

"She's still got the cigar I believe."

Being at the side of the stage to watch David Bowie is one of Tony's most treasured memories

Tony worked alongside his wife, Jo, at the Pyramid Stage, and their daughter continues the tradition

For all the pressure of playing the Pyramid Stage, the atmosphere behind the scenes is serene and relaxed.

Bands stretch out on sofas, or dawdle over to the central bar for a cappuccino. In 2017, Nile Rodgers made this reporter a cup of tea and asked for advice on his setlist; while Kenny Rogers spent his pre-show warm-up talking about tennis ("I once had a higher doubles ranking the Bjorn Borg," he told BBC Radio 5 Live).

Part of the reason is that it's a family affair. As part of the backstage management, Szymkow worked alongside his wife Jo, son Frank and daughter Xanthe - a fashion student, who got roped in to fix Beyonce's dancers' costumes in 2011.

"That's just the nature of Glastonbury," he says. "The original ethos from 1971 has shone through: Everybody helps out."

After 36 years of service, Szymkow retired after ushering Ed Sheeran on stage at the 2017 festival. This year, he's back as a punter for the first time in his life.

"Here I am walking around free, with no radio and no responsibility, and it's a wonderful feeling," he laughs.

"There's a saying at Glastonbury: 'There are no problems, just opportunities to excel'.

"I walked past someone who was given a fantastic 'opportunity to excel' this morning, and I was so glad I'm out of that loop.

"We only have the less demanding 'riders' of our grandchildren Ernest and Clarice at this festival."

An earlier version of this story incorrectly stated that Tony managed the Pyramid Stage. We are happy to clarify that he was part of a larger team, including his wife Jo, who worked behind the scenes on the festival's main stage.

Follow us on Facebook, external, on Twitter @BBCNewsEnts, external, or on Instagram at bbcnewsents, external. If you have a story suggestion email entertainment.news@bbc.co.uk, external.

- Published29 June 2019

- Published28 June 2019

- Published28 June 2019