Capturing the art and beauty of memorials

- Published

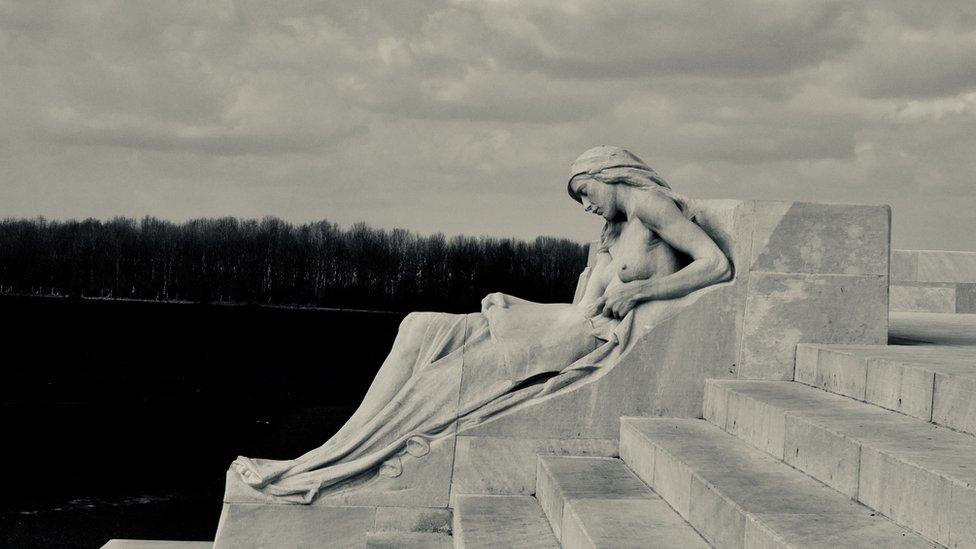

Monument in Argentan

Gabrielle Crawford has worked for years as a professional photographer. Now living in Normandy she was puzzled by how few people took an interest in France's monuments to the dead of two world wars. So, having secured a commission, she set about creating a photo collection of the monuments - trying to bring a female perspective to these commemorative works of art.

Gabrielle (who was once married to the actor Michael Crawford of Some Mothers Do 'Ave 'Em fame ) remembers being aware of war monuments even when she was very young.

"My father was a naval surgeon and on Christmas Day we'd go to the hospital to shake hands with the sailors after church, where there'd always be a monument to the dead.

"And each summer we went on holiday to Italy. Driving down through France my father would point out the war memorials and I'd wonder about the stories behind them. Here I am years later having photographed many of them."

Gabrielle Crawford married the actor Michael Crawford in France

France has been a fixture in her life. In 1965 in the British embassy in Paris she married Michael Crawford. That marriage ended but he and their children have been to Normandy to see her photographic exhibition at the Mont-Ormel museum, a few miles from where she lives.

In August 1944, Mont-Ormel was the site of a bloody engagement in the battle for Normandy, which followed the D-Day landings of 6 June. Gabrielle Crawford was commissioned by the Orne department to create a photographic record of France's monuments to the dead of two world wars. The collection would then be held at the museum.

"When I came to live in Normandy I was taken by the number of war memorials there are - many very beautifully made with amazing detail. In the cities they were designed by architects. But in small towns and villages often they were paid for by local subscription: they're less grand and perhaps more touching. Often they feature images representing the ordinary French people who died when the Germans invaded or who were deported afterwards.

"British war monuments are almost all to young men who went abroad to die. But in France it's more complex and often you see children on them and old people and the women who suffered at home. That was the French experience."

An example of a Poilu, the French infantrymen of the 1914-18 war, whose monuments are often painted and can look "comic"

She finally chose around 60 images to show in the exhibition. She says it annoys her that some of the original monuments have been moved over the years and are hard to see up close.

"That's why in some cases I crop in on faces. Some show real pain and anger but that detail is lost when people speed by in their cars. I did a huge amount of travelling to find the monuments but often when you get to a place it will only be people over 70 who have any idea where they are."

So did French friends think it odd that someone from Britain would take an interest in the monuments? Gabrielle says people were more surprised at a woman taking an interest.

A sculpture in Bois Grenier

"I think the whole issue of war memorials is seen usually as a male thing. But as the pictures mounted up I looked at my work and I thought it's very clearly a woman's eye, a female view. And I hope that's what's new about the collection people will find at Mont-Ormel. I hope the pictures will be seen in other places too.

"At least in the north of France people were memorialising invasion and you will see an image of a mother weeping or a daughter terrified because her father has suddenly gone. Relatively few show heroic soldiers and I decided to exclude memorials to an individual general or whatever - but they're pretty rare anyway."

Vimy memorial

Gabrielle says there's a real power to simple stone or concrete monuments, which often include the classic Poilus - the French infantrymen of the 1914-18 war. (The word roughly equates to the British term Tommy.)

"Often they'll be life-size or near life-size and people repainted their coats in blue and the moustache in black. They can end up looking very slightly comic but French people still have an affection for them, perhaps more than for more grandiose monuments."

Utah beach memorial

"And you have to remember that in France the state and the church are separate. So war memorials weren't allowed to have a religious aspect at all: it was more something a particular village would do."

Gabrielle is pleased her exhibition has coincided with the 75th anniversary of D-Day. There are some specific World War Two monuments but often names were added to monuments of World War One.

"I've had to limit myself for now to Normandy and a little bit beyond - there are monuments elsewhere I could have included in Picardy and even in Belgium.

"But the main aim was to remind people that these monuments exist and are worth looking at. They sometimes contain surprising detail of the suffering wars brought - not just to the soldiers but to parents and wives and children too."

Gabrielle Crawford's photographic exhibition runs at the Mont-Ormel museum in Normandy until 1 September.

Follow us on Facebook, external, on Twitter @BBCNewsEnts, external, or on Instagram at bbcnewsents, external. If you have a story suggestion email entertainment.news@bbc.co.uk, external.