From Queen to Springsteen: Why are there so many music films now?

- Published

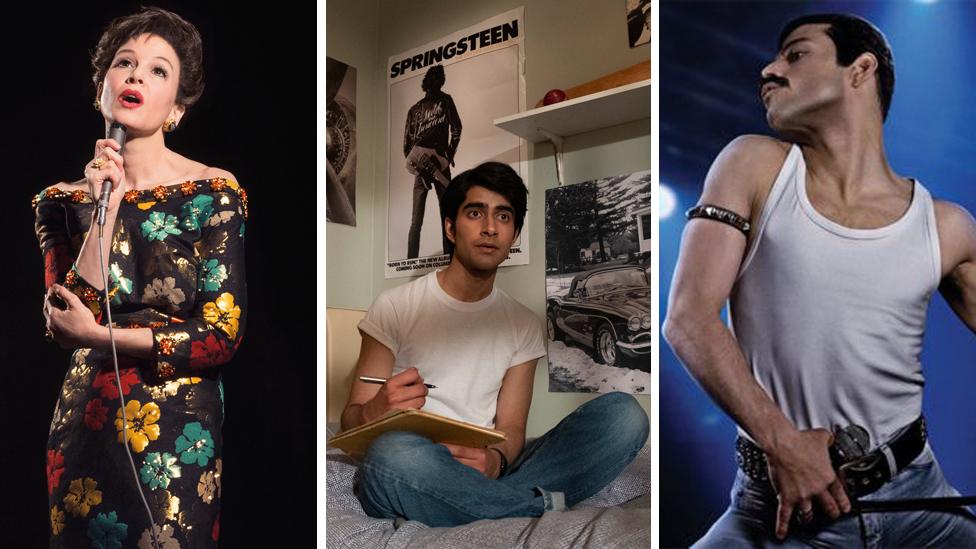

Renée Zellweger as Judy Garland, Viveik Kalra as the Bruce Springsteen-mad Javed and Rami Malek as Freddie Mercury

This year will be remembered for the UK leaving the EU (maybe), England winning a Cricket World Cup (finally), and the latest utterly pointless social craze - the bottle cap challenge (nope, me neither).

For cinema-goers though, 2019 has been the year of the music film.

It's not yet September and we've already had movies powered by the sonic might of Sir Elton John, The Beatles, Motley Crue and Bruce Springsteen, as well rockumentaries on Liam Gallagher, Bob Dylan and Leonard Cohen.

With Judy Garland, Michael Hutchence, Suzi Quatro and George Michael-flavoured features still to come, by Christmas we'll have seen enough singers at the pictures to fill up an entire 2020 wall calendar.

Not to mention the big name remakes of classic musical animations like The Lion King, Aladdin, and the curious trailer for the cinematic adaptation of the stage musical Cats.

So what exactly is driving this resurgence in on-screen sing-alongs?

Music is being used 'as a character'

Eliza and Javed: Born to Run

Blinded by the Light hit the cinemas last week and tells the story of Javed - a British-Pakistani teen growing up in Luton in the late 1980s.

It's a typical coming-of-age tale of growing pains, culture clashes, and breaking free, however, Javed's journey is carried stylishly via the vehicle of his newfound fave, Bruce Springsteen's music.

"This film doesn't have any stars," explains scriptwriter Sarfraz Manzoor. "But the biggest star it has is Springsteen and that's a familiar thing that might bring people in."

He adds: "We basically made it so that the music was a character in the film which would help the story along and explain why Springsteen mattered to this kid."

The trick of tapping into our "unique relationship with music" is not exactly new, as fans of Martin Scorsese and Quentin Tarantino will tell you. But it is being employed in more and more creative manners, in films like Guardians of the Galaxy (Peter Quill's Awesome Mixtape) and shows like Stranger Things (retro 80s-style synths) and Killing Eve.

(Music is so integral to Peaky Blinders they're hosting their own festival).

When adapting his book for the big screen, Manzoor made Springsteen tracks like Dancing in the Dark and other songs from that era central to the script from day one to "navigate you through the story and fit particular emotional moments in the film".

The YMCA routine needs a little work still...

"I was listening to all the hits from 1987 just as a way of getting myself into that space," the writer says.

"The first thing that really unlocked it was the Pet Shop Boys' It's a Sin. If you listen to the lyrics it's basically about someone who is not able to do what they want and that's exactly what Javed is like! I thought, we've got to try and start the film with it because it would first get everyone into 1987 and also tell them what the theme of the film is."

Other "cheesy" tracks like Marrs' Pump Up the Volume, Mary's Prayer by Danny Wilson and Tiffany's I Think We're Alone Now were also used to "provide a counterpoint" to The Boss.

"When I was growing up I was loving all that pop music but ultimately it's quite vacuous, and a bit pointless. So when I found Springsteen's music it spoke to me in a much more profound way."

The protagonist, based loosely on the writer's younger self (minus the love interest, he confesses) ultimately heads off to Manchester to study and Manzoor says it would be fun to follow him with a 1989-based sequel.

If he does, expect less Bruce and more baggy/rave bangers driving the plot.

'Music is the number one trigger for nostalgia'

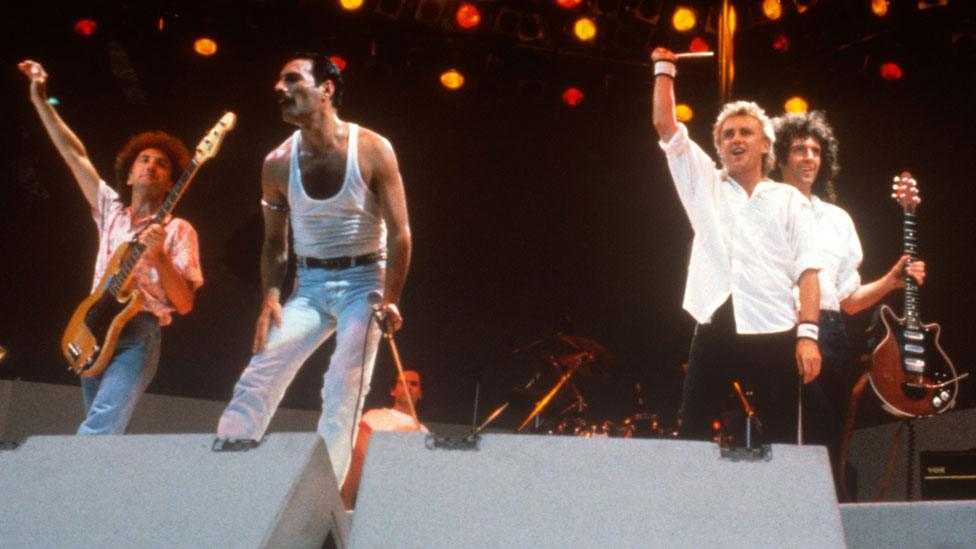

Queen's performance at Live Aid in 1985 provides the peg for the Bo-Rap movie

Aah nostalgia eh? It's not what it was...

According to the boffins at Spotify we make the most enduring emotional connections to the songs we enjoyed in our mid-late teenage years. Therefore, the feel-good-factor created by hearing old songs we love, in movies like Rocketman, Yesterday and Bohemian Rhapsody, help us to momentarily turn back time.

Nowadays these tracks, along with those from A Star is Born and Mamma Mia!, are all easily available online, meaning there's now "a ready-made audience for music-driven movies."

"The trend towards music-driven movies can be considered part of a wider trend of nostalgia and we know from our own research that music is the number one trigger for nostalgia," says Spotify's head of music for UK and Ireland, Sulinna Ong.

"Being able to tap into that via the big screen has huge appeal for creators, filmmakers, artists and fans alike."

She notes you don't have to have been one of the lucky ones at Live Aid in 1985 to enjoy the sense of nostalgia you get from listening to the soundtrack for Bohemian Rhapsody. "If you grew up listening to the band, it brought it all back."

Hands up if you were there at Wembley Stadium

(L-R) Ed Sheeran, Lily James and Himesh Patel from Yesterday, Rami Malek with his best actor Oscar trophy for Bohemian Rhapdosy, and Rocketman star Taron Egerton alongside director Dexter Fletcher

The streaming giants employ "throwback" features to try to extract this emotional gold too and while it allows easy nostalgic listening for older listeners, their figures suggest younger listeners are incredibly interested in discovering iconic artists too.

Since the mega success of the Oscar-decorated Bo-Rap, streams of Queen songs surged by 33% and 70% of those listeners were under 35.

"Queen are more popular than ever, not just among baby boomers and Gen' Xers, but with millennials," adds Ong.

"The key to explaining why we see a lot of younger listeners showing an interest in artists such as Queen, The Beatles and The Boss is their continued cultural relevance."

Other popular musicians including Celine Dion and the Creation Records mob are set to get the biopic treatment next year, so don't be surprised when a host of re-issued albums and tour announcements soon follow.

People crave 'escapism' during uncertain times

Judy Garland: Swing when you're not winning

"Forget your troubles, come on get happy!" sang Judy Garland in Summer Stock back in 1950, but she could just as easily be singing it today.

According to the BFI, external, the musical film enjoyed two early "golden eras": First in the 1930s, with US productions like 42nd Street, as The Great Depression took hold, and then again with the MGM films - like Singin' in the Rain - during and directly after the Second World War.

Robin Baker, who's curated their upcoming celebration of BFI Musicals: The Greatest Show on Screen, believes it's no coincidence that similar trends are emerging in cinemas once again.

"Both times you're dealing with society under stress, wanting to escape their woes and troubles," says Baker, who pinpoints the success of La La Land and The Greatest Showman as heralding in the new wave.

"To me right now, in an age dominated by international anxiety, whether it's climate change, Trump, or political instability here and a nation divided - people want an escape from that."

Mia (Emma Stone) and Sebastian (Ryan Gosling) hot-step their way out of reality and into La La Land, while Hugh Jackman is The Greatest Showman

Musicals and music films, he concludes, also allow us to come together and confront harsh truths, through a fantastical prism.

"You can look at some of the biggest ones that deal with very serious issues but what they do is allow you to kind of flip into another world that is exaggerated and larger-than-life."

A world in which The Beatles don't exist, but there's a big singing cat with Beyonce's voice and where Renée Zellweger is a faded Broadway star named Judy, perhaps?

- Published14 August 2019

- Published19 June 2019

- Published18 May 2019

- Published23 May 2019

- Published1 November 2018