Skepta glimpses the 'future of rave' in Manchester, and it's phoneless

- Published

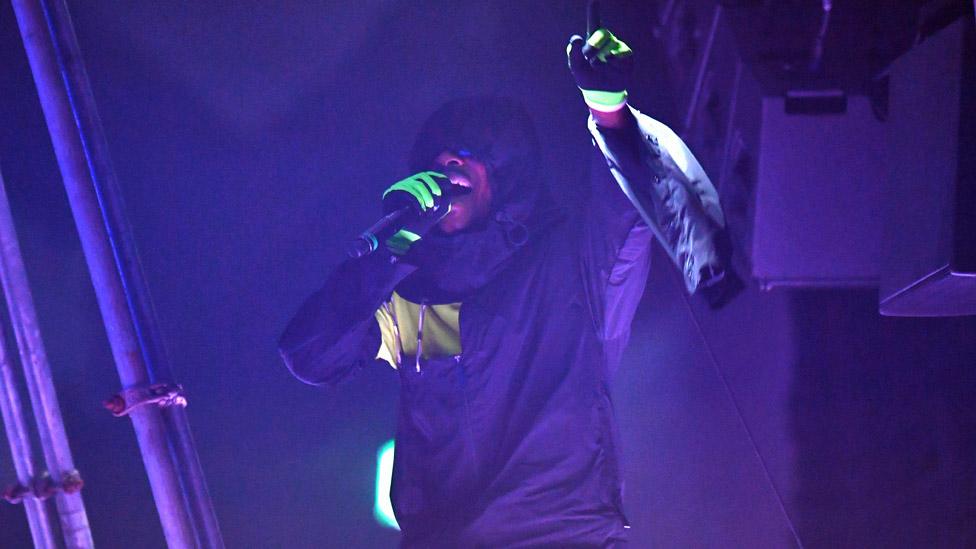

Skepta on stage, and not a phone screen in sight

Grime star Skepta has staged a string of experimental gigs using technologies like "mixed reality" and "spatial computing" - but without smartphones.

We meet under a motorway flyover near Manchester Piccadilly station - 100 or so ravers ready to be led to a secret location for a next-generation gig experience.

We follow crew members wearing rave masks and single yellow gloves on a 10-minute walking tour of urban dereliction. Some people are even bundled into cars for added theatrical effect and transported to the venue, not knowing where they're going.

It's all presumably designed to hark back to the thrill of the acid house days when ravers would only find out a party location at the last minute. Except this is a highly organised event, and our guides have undoubtedly been briefed about health and safety.

We're eventually led to the back of a grimy warehouse, next to a yard where scrap lorries are parked, and are given soft, slim pouches to slip our phones into before they are sealed for the night. The Yondr pouches have become popular with some musicians and comedians who are fed up with audiences watching live shows through their screens.

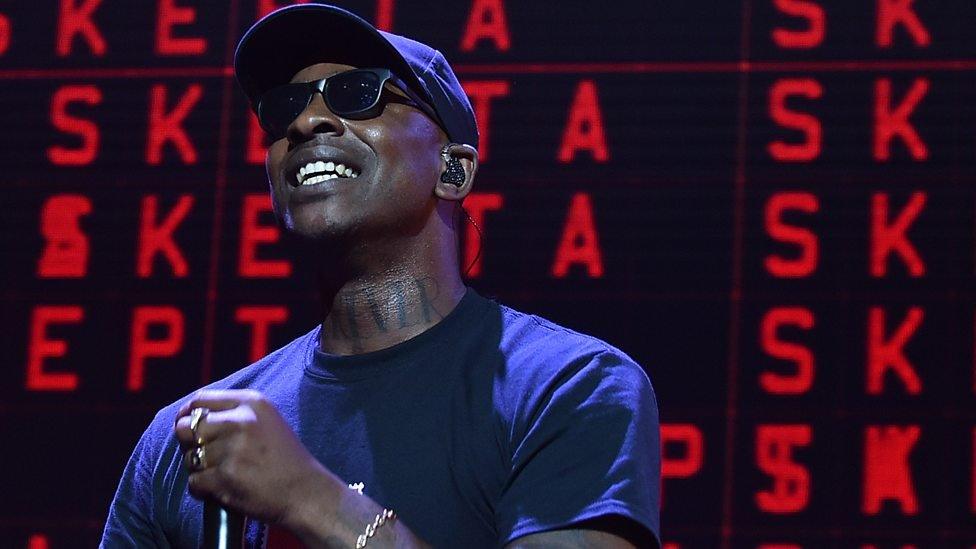

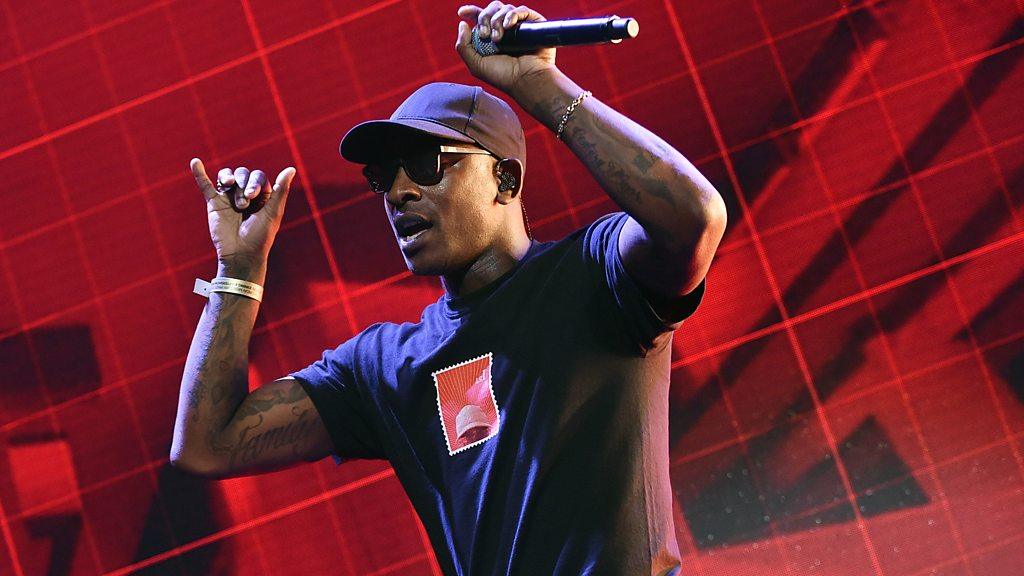

Skepta is one of those. Speaking at the Manchester International Festival (MIF) launch in March, the Mercury Prize-winning MC said nightclubs had "turned into places for this new individualism, where people are just on their phones to have a 'fake good time'". When MIF approached him to create a special show, he decided phones would be banned.

The night took place in old railway arches

A fan trying out augmented reality goggles

MIF specialises in staging shows that are out of the ordinary so the phone ban isn't the only unusual thing about Dystopia987, which ran for three nights. Skepta created it with cutting-edge creative studio TEM, who experiment with emerging technologies; and award-winning playwright Dawn King.

Details were deliberately scarce but the show was billed as "a journey into the future of rave" involving "a series of individual and collective experiences [that] have been developed using mixed reality". Mixed reality is where virtual and physical objects exist together, and people can supposedly interact with digital creations in the real world.

Entering the venue, we're told about something called Intelligent Rave Software, and some sort of higher omnipotent being called Darmian (possibly named after Manchester United's Matteo Darmian, but I may have misheard). We are each given a small coloured token that is a "token of thanks from Darmian".

"Your interaction is required," Darmian informs us in headphones we are given on the way in. Hippy-protest placards with slogans like "Free your ego", "Free your spirit" and "Free from phones" hang on the walls. Someone is holding a prosthetic leg. In the next room - a long, large railway arch - a DJ is at a central podium. She looks real.

Skepta's warm-up DJ

A fan after visiting one of the face paint artists

Curious about what is meant to happen, I ask a crew member wearing a red face mask what the tokens are for. "I can either give you a handshake, a high five or a hug." I opt for the hug. He feels real. "Now I can either give you a back rub or a group experience."

Warily, I join a group huddle with three crew members. We must each give a compliment to the person on our left. The first rave leader whispers something to the person next to him, who whispers to me that he likes the flashing rave glasses I have just bought in an attempt to fit in. I compliment the young woman to my left on her striking pink eye make-up.

Which is all lovely, but there's not much of a storyline, and the only obvious sign of "mixed reality" is a small red room in the corner where you can try a pair of Magic Leap goggles that overlay some pretty underwhelming graphics onto your vision.

The venue fills up as more people are led there until it reaches its 1,000 capacity. The DJ stays on the podium until eventually an announcement says we are ready to take the next step, and plastic sheeting is ripped away, revealing two doorways to an adjoining room.

It's a mirror of the previous room - a long, thin tunnel with blackened brick walls and a high arched ceiling. The stage is a scaffold tower planted in the centre of the room like the leg of a bridge in a river of ravers.

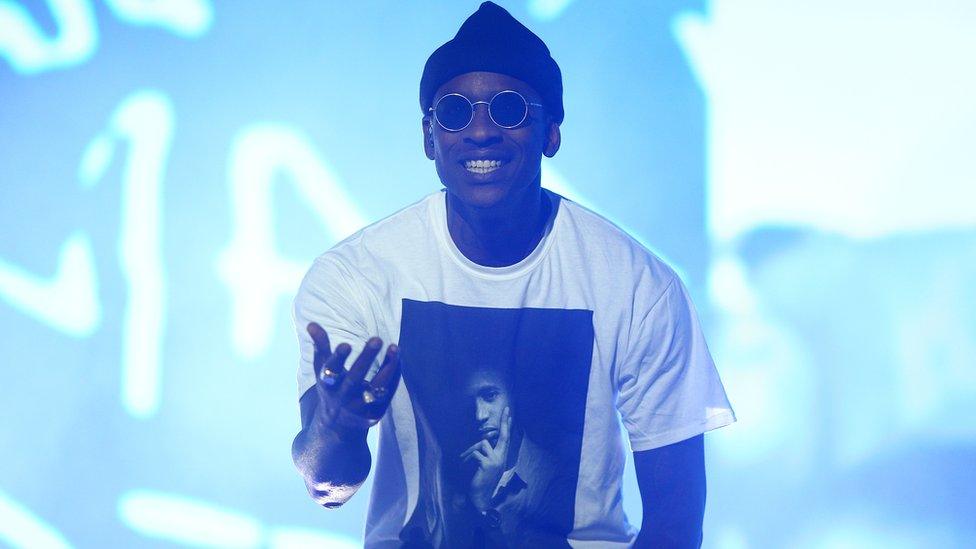

Skepta, hooded and wearing neon gloves, circles the tower on a platform from where he can perform his pounding set to the melee of fans on either side. Someone is waving a prosthetic arm in the air like they just don't care. When the MC addresses the crowd between songs, it's to tell us to show each other our love, or to say we're more free when we're not posting to Instagram.

"I was bored of everybody in the club telling everybody outside the club how much of a good time they're having," Skepta says. There are big cheers as he tells fans that tonight they are not their Instagram name, they are not their Twitter name. "You're yourself, right here, together with everybody, right here, now."

It seems he is trying hard to recapture an energy that came effortlessly in this city in the legendary "second summer of love" 30 years ago. "This is one of the best things I've experienced in my whole life," he marvels.

Normally there would be a sea of screens at a gig, but here the only lights in the crowd are flashing LED eyelashes, illuminated cheek beads and fairy light necklaces. "I can't predict the future but I know it's going to be something like this," Skepta says.

Impressive visuals are projected onto clear screens surrounding the stage's central tower, but Skepta proves that the human connection with a mesmerising performer is more powerful than any technology. And it looks like the "future of rave" actually involves reclaiming an unselfconscious spirit from the past. The night's best use of tech involves putting it into pouches. The evening will live in the memory of those who were there, rather than their camera roll.

The crowd filters into the damp street, having had one of the nights of their lives. After getting their pouches unlocked on the way out, they check their phones and then head home.

More from the Manchester International Festival

Follow us on Facebook, external, on Twitter @BBCNewsEnts, external, or on Instagram at bbcnewsents, external. If you have a story suggestion email entertainment.news@bbc.co.uk, external.

- Published16 September 2016

- Published16 September 2016

- Published5 April 2018

- Published1 March 2018

- Published28 July 2017