Shambala: The festival that banned cow’s milk, meat and glitter

- Published

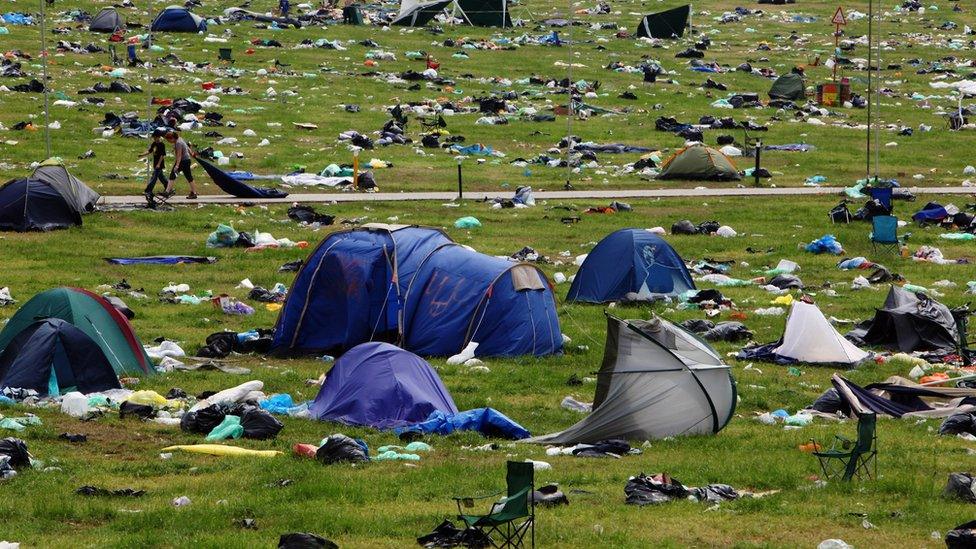

Shambala Festival attracts a sustainability-minded audience

Phone signal, flushing toilets and a simple shower are luxuries that we're used to not having at a festival. But could you handle no meat, fish, cow's milk or the ultimate festival favourite - glitter?

In the name of sustainability, Shambala Festival has done just that and stopped serving meat, cow's milk in hot drinks and told their audience not to wear glitter.

The UK's booming festival scene has come under fire for its impact on the environment. But since kicking off 19 years ago, Shambala has reduced its carbon footprint by over 80%, achieved 100% renewable power, and stopped selling disposable plastics.

The music festival takes place every August in a secret location in Northamptonshire and features 200 acts across 12 live stages.

Its green ethos attracts like-minded attendees, with some opting to cycle to the event to ensure they're not adding to vehicle emissions.

Tom Hague cycled to Shambala because it's more environmentally friendly

Tom Hague is one of the many people who took part in a guided cycling tour, external to the festival. He cycled more than 100 miles over two days to get there.

"Cycling is a better way to get there rather than turning up in your own car or turning up on bus.

"It feels like more of an achievement, you've done some exercise and you've put yourself in a nice condition to enjoy the rest of the weekend," says Tom.

This year, for the first time, all hot drinks purchased on site were free of cow's milk. Oat, coconut, soy and hemp milk were used as replacements.

Prior to the festival Jess Ford, another attendee who also cycled to the event, wasn't sure how she'd cope without cow's milk in her coffee.

"I have to admit for me that's quite a step, it's quite a bold move," she says.

Jess Ford dressed up as a butterfly for Shambala and cycled to the festival for the second year in a row

Regardless, Jess thinks cutting cow's milk will make people more aware of the impact that their choices are making.

"You never know by the end of it I might love oat milk," she adds.

It's not only the festival punters who are encouraged to be environmentally sustainable, the crew and artists are too.

Joe Henwood is a musician and club manager at the Pink Flamingo Jazz Club, a secret venue with live jazz music that you have to "find" as it's not on the line-up or the festival map.

When kitting out the venue with furniture, Joe gave himself a "rule" to not buy anything new.

"It's all second hand because I'm kind of in the belief that there's enough furniture and stuff in the world already, so you can just buy it all second hand and we go to charity shops," Joe says.

The crew working at the Pink Flamingo Jazz Bar tried to lower their vehicle emissions by car sharing

For rigging the stage, Joe used re-usable cable ties.

Cable ties, glitter, plastic straws and drinks bottles are all examples of single-use plastic.

In 2017, more than one million plastic bottles were sold at Glastonbury - this year single-use plastic bottles were banned from sale at the festival.

Other festivals are also cracking down, with more than 60 independent British festivals pledging to rid their sites of single-use plastic by 2021.

The world's largest concert promoter, Live Nation, has also also said it will eliminate single-use plastics at its festivals by 2021.

This means that events like Reading and Leeds, Wireless, Latitude and Download will go plastic free.

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

One festival to already ban the sale of single-use plastics is 2000trees, a rock, punk and alternative music festival in Cheltenham.

"Banning plastic isn't difficult from an operational point of view," says 2000trees Festival co-founder and creative director Rob Scarlett. "It's just difficult making everyone do it," he says, referring to the fact that due to miscommunication one of the 30 traders at the festival brought in and sold plastic bottles on site.

However, what is "difficult", Rob says, is changing audience transport habits which have a "direct impact on peoples enjoyment and their ease."

Audience travel typically contributes to around 80% of a festival's carbon footprint, external.

Instead of putting on glitter - which counts as a single-use plastic - Shambala encourages wearing fancy dress, painting your face or wearing a mask

So, will banning single-use plastic make that much of a difference? Tom De Brabant, a live sound engineer with 12 years' experience working at festivals, doesn't think so.

"People aren't thinking about the long-term stuff like the two diesel generators pumping away behind every stage and the trucks, some of them half loaded, that are doing three or 400 miles to drop some kit off at a festival," he says.

"You don't see that on the floor at the end of the festival."

Tom De Brabant says music festivals are "inherently bad" for the environment

Tom has to transport heavy production kit to and from venues and is aware of his environmental footprint, which he says "isn't small".

"In terms of my job, my personal impact is huge.

"I live in the Cotswolds and there are not a lot of big music venues here, so I probably do 30,000 miles a year just driving to gigs and to work in my diesel car."

Shambala is powered completely by renewable energy so they don't have a diesel generator pumping backstage.

The festival reduced some of their energy requirements by switching to energy efficient equipment and LED lighting

However, because the operational carbon footprint of the festival is small, travel to and from the festival makes up over 90% of their overall greenhouse gas emissions.

Shambala say they're "determined to reduce this" and encourage everyone to travel to the event by train, coach, car share and cycling. As an incentive, coach and cycling tickets are £15 cheaper than the regular festival tickets.

- Published23 June 2019

- Published8 May 2019

- Published24 May 2019