1917: Faulty lighters and other problems with making one-shot films

- Published

George MacKay plays Lance Corporal Schofield in 1917

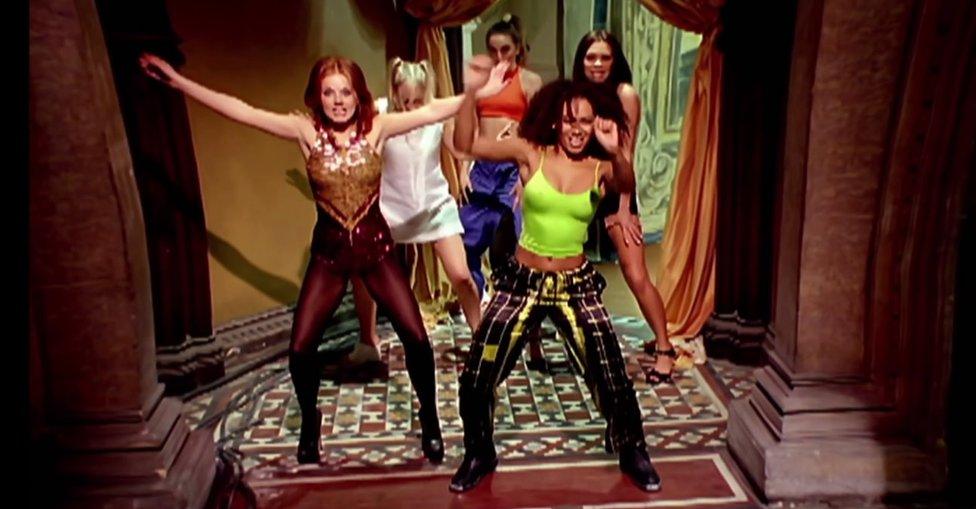

On the surface, you might think war film 1917 would have little in common with the music video for Wannabe by the Spice Girls.

But you'd be wrong.

Sir Sam Mendes's two-hour World War One epic is notable not just for its Oscar momentum and critical acclaim, but also for the fact it appears to have been shot in one continuous take. No cutaways, no scene changes, just a single, floating shot.

The camera follows Lance Corporals Schofield and Blake (played by George MacKay and Dean-Charles Chapman) as they risk their lives by crossing enemy lines. The pair must deliver a crucial message to stop their comrades walking into a deadly trap.

Their mission is slightly more dangerous than the one undertaken in 1996 by the Spice Girls, who were followed by a single camera from room to room as they caused chaos at a London hotel, but the principle is the same.

"You want to lock the audience together with the central characters, creating the feeling that they can't get out," explains Sir Sam, who has also directed American Beauty and the James Bond films Skyfall and Spectre.

"But when we did the first preview screening, you could feel that visceral sense in the audience of being connected, moment by moment, and I think that is something to do with the one shot, and the fact you can feel the time passing."

Sir Sam Mendes also used a single shot for the opening sequence of Spectre

But this treatment isn't without its issues.

Perhaps the most problematic moment of filming 1917 was what Sir Sam refers to as "lighter-gate" - a scene where a faulty prop meant having to re-shoot an entire sequence.

"Andrew, in his only scene, made more mistakes than anyone else," the director affectionately jokes, referring to Fleabag star Andrew Scott, who was required to light a cigarette during his brief appearance in the film.

"Never smoke, ever," Scott picks up. "On anything - on stage, on screen - never use a cigarette lighter."

Sir Sam expands: "You can have seven minutes of magic, and then if someone trips, or a lighter doesn't work, or if an actor forgets half a line, it means none of it is useable and you have to start again."

Scott felt particularly bad given he plays a minor character, pointing out: "You have to work alongside the camera team and the extras but the great challenge of it is you don't want to mess it up, because you're only in it for five minutes, you don't want to be that guy."

The cigarette behind Andrew Scott's ear caused all kinds of issues during filming

"There were days where we did see-saw between thinking 'why are we doing this to ourselves', and thinking 'this is the only way to work'," Sir Sam says. "The feeling when you got it was so great, that you wanted to do it again. But there were some tough days."

While very few films and music videos are genuinely captured in a single take, a bit of camera trickery and skilful editing helps make it look like they were.

As anyone who watched recent BBC drama The Capture will know, something like a bus passing in front of the camera can be a clever way to make a cut or stitch together two takes, without the viewer noticing the transition.

The finished product allows the viewer to feel like they're going on one long and uninterrupted journey with the characters - and it's a tactic which has been used a great deal in film and TV.

Continuous takes

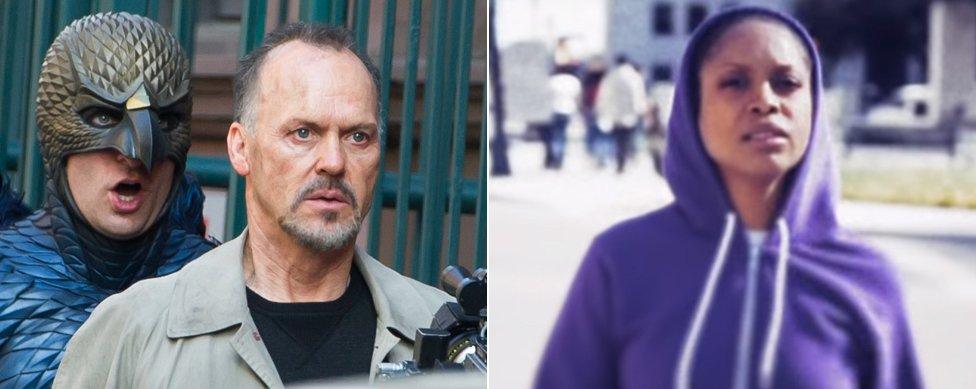

Birdman, which won the Oscar for best picture in 2014, is probably the most recent and high profile example of the one-shot technique. Viewers follow a faded US actor, played by Michael Keaton, through an emotional tail-spin. Director Alejandro Gonzalez Inarritu said, external he shot it to look like one take because he "wanted this character to be submerged in an inescapable reality".

Fans of Sam Mendes will know he dipped his toe in the one-shot waters for the opening sequence of Spectre, which follows Daniel Craig's James Bond as he climbs out of a hotel room window in Mexico City to chase after a villain. "It was a very visceral way for the audience to be sucked into the film," said cinematographer Hoyte van Hoytema, external.

Lost In London was particularly ambitious. Woody Harrelson's directorial debut was filmed in London in the middle of the night back in 2016. It used only one camera, in what genuinely was one single take, and was broadcast live to 500 cinemas in the US. The whole project was almost derailed when Waterloo Bridge, one of the key filming locations, was closed hours before the shoot.

Victoria, a German heist film shot in 2015, was also genuinely filmed in a single take. Its makers had to discard the first two attempts, external, but the third was the one which made the finished film.

Michael Keaton in Birdman and Erykah Badu in her music video for Window Seat

Going much further back, Alfred Hitchcock's 1948 film Rope was shot not only made to look like it was shot in one continuous take, but remained in one single location for the entire film - a Manhattan apartment where a murder takes place. Hitchcock also used the one-shot technique in 1949's Under Capricorn.

When it comes to music videos, there are hundreds of examples. A few, like Alanis Morisette's Head Over Feet, external, genuinely were shot in one take - which was quite easy in that particular case as the entire video is just a close-up of Morisette's face as she sings.

Erykah Badu's Window Seat, external saw her gradually strip naked on a Dallas street over the course of the song, landing her in trouble with the authorities.

Other examples which were helped by a bit of camera trickery to create the one-shot effect include Sia's Chandelier, external, Taylor Swift's We Are Never Ever Getting Back Together, external, and the aforementioned Spice Girls video for Wannabe, external.

Veteran cinematographer Roger Deakins recalls: "[Mendes] sent me the script, and on the cover page it said 'this is envisioned as a single shot', and I said to my wife 'that must be a mistake'. We did a lot of rehearsals and a lot of testing... it wasn't until a few days before shooting that we felt it was makeable."

Pulling off such a high-wire act has paid dividends for the film already - 1917 has already won two Golden Globes and picked up nine Bafta nominations earlier this week.

So how many different takes were involved, only for them to be stitched together to make the film look seamless?

"That's a secret!" laughs Deakins. "But you can probably work it out. We shot around 65 days, and the longest take was around nine minutes, so you could do the math.

Sir Sam said there were some "tough days" on set trying to perfect the technique

"The major difficulty," he continues, "was getting across the terrain, and doing some of those really intense, sensitive scenes, and making it all feel like a single piece.

"So you're using a lot of techniques - stabiliser systems, wire cameras - but I think for me the trick was to try and make it feel like one camera all the time. That was the biggest challenge. That and the weather."

Follow us on Facebook, external, or on Twitter @BBCNewsEnts, external. If you have a story suggestion email entertainment.news@bbc.co.uk, external.

- Published18 September 2019